'Listen to the vibrations': Mars Hill students share on WNC's shape note singing tradition

MARS HILL - Western Carolina, and Madison County in particular, boasts a historically important and extensive musical background that dates back generations, chronicled in part by Cecil Sharp's 1932 "English Folk-Songs from the Southern Appalachians."

In 1928, Madison County resident Bascom Lamar Lunsford - a musician and folklorist who dedicated his life to collecting and promoting the music of the region - founded the Mountain Dance and Folk Festival in Asheville. The festival, which today bears the name of its founder and is produced by Mars Hill University, is believed to be the earliest folk festival in the United States.

But around the time of that festival's founding, there was another musical custom that was wildly popular throughout the region: shape note singing.

The News-Record & Sentinel sat down with Mars Hill University students on the final day of class in their shape note singing course, a part of the university's Appalachian Studies department, which explores the history, cultural and natural environment of Southern Appalachia. Leila Weinstein, the program coordinator for the university's Ramsey Center for Appalachian Studies, taught the shape note singing class.

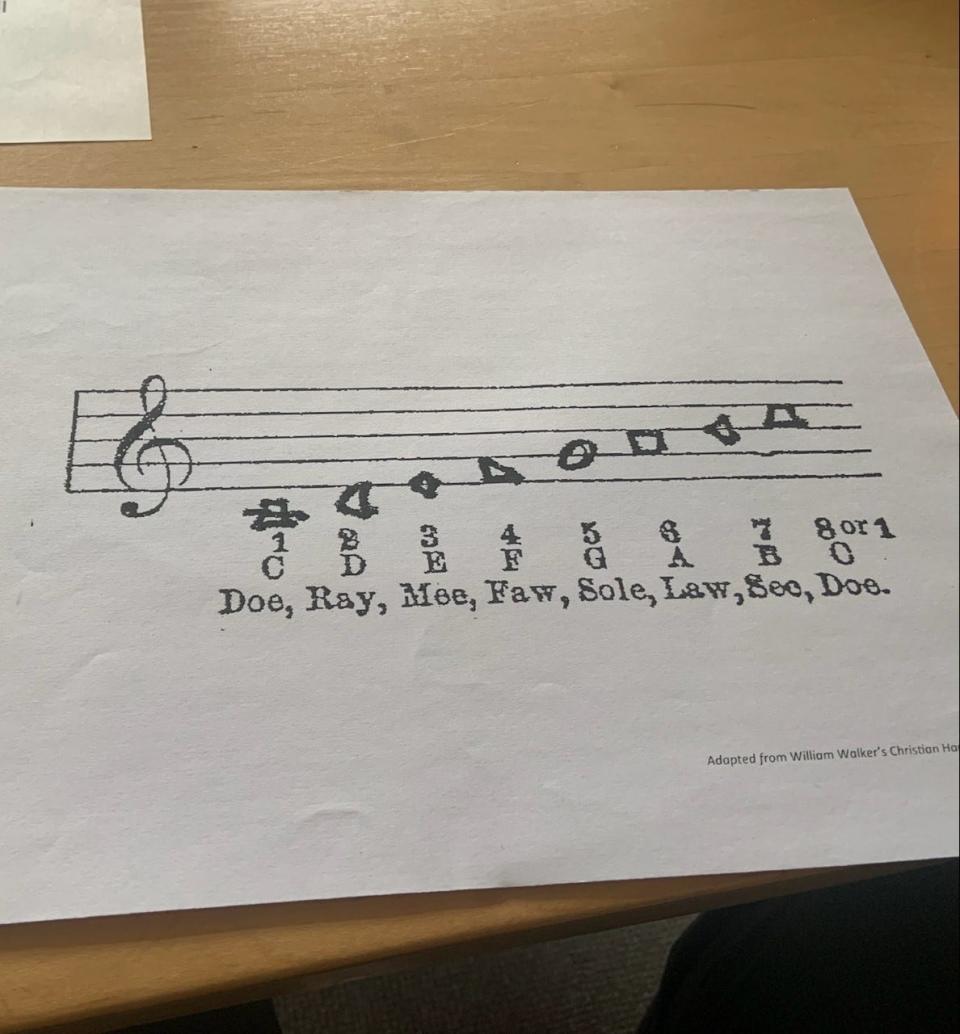

"Shape notes are a musical notation that is used to simplify standard music theory," said Megan Walters, one of the students in the class.

"On a standard music theory, you have a staff with the little round-headed notes. In shape notes, each pitch on solfége - the do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, do (pattern) - has a different shape. So, one syllable might be a triangle. (In shape note singing), Do is a trapezoid, and re is a crescent, and so on and so forth, versus standard music theory, where it will all be circular heads. By using shape note, you don't have to know pitches. You know the intervals, but you don't need to know if the song starts on A, or B-flat. It basically eliminates the necessity for a key."

According to Caleb Colclasure, one of eight students in the class, the class dealt specifically with the patented shape notes from "The Christian Harmony," a shape note hymn and tune book released in 1866 by William Walker.

The shape note tradition predates the book's publication by roughly 50 years though, according to Weinstein.

"It is sacred singing by Christians specifically, and it started as a way to improve congregational singing," Weinstein said. "Before the shapes were invented, in the 1700s there were a lot of singing masters who would go around to areas and teach people how to sing, like a summer school. This was because one of the hymnals that came over in the early colonial period didn't have notes in it at all. It was just words. So you can picture over the generations, unless you have people who are really excellent singers, with the absence of instruments, the singing is going to decline.

"So, there were a lot of drives to improve congregational singing. This grew out of that. Like a lot of folk music, a lot of music in rural America is designed specifically so that you can participate in it without going to school. Dance calling and square dance is the same thing, where anybody can go because they're hollering out the instructions. You can just go and participate. Shape notes are similar to that."

According to Weinstein, the class is an oral history practicum, so the students learn how to do oral histories hands on.

As part of this immersive learning experience, the class interviewed June Smathers Jolley, whose father Quay Smathers was a shape note singer in Haywood County. The class also interviewed Madison County Arts Council Executive Director Laura Boosinger, who is also an accomplished banjo player.

One of the Smathers' relatives, Darian, is a student in the class, too.

"We grew up in this tradition," Smathers said. "I grew up right down the road from the oldest singing tradition in North Carolina, which is Old Folks Day at Morning Star (Methodist Church in Canton)."

Darian Smathers' classmate Kurstin Wills discovered she also had a connection with the family, as Wills went to the same church, Mount Zion Baptist, in the Bluff community of Hot Springs.

"My mamaw was at one of (Quay Smathers') singing things, and she has one of the little cassette tapes of where they recorded it at my church," Wills said.

The tradition today

While the shape note singing scene may not be as vibrant as in the first half of the 1900s, there are still opportunities to attend a weekend singing, as many of the students did this semester.

Taylor Zima, who grew up in Asheville, said she enrolled in the Appalachian Studies minor on a recommendation from her adviser.

"We started learning about this tradition, and then you meet all these amazing people and you learn everything about their lives, and next thing you know you're spending a Saturday at a singing in Marshall about something that you didn't know about six months ago," Zima said. "Now, I have a 'Christian Harmony' hymnal sitting on my shelf. I'm going to be 60 one day at one of these singings, and no one in my family is going to know what I'm on about."

Darian Smathers recalled the reflections of one singer at the Singing on the River event at the Madison County Arts Council Nov. 19.

"She said something along the lines of, 'We're going to sing until we can't sing anymore, and then we'll get people to prop us up so that we can listen to the vibrations,'" Smathers said. "That makes no sense until you're there and you can experience it. It's ancient and emotional. It feels like 'the tinglies.'"

According to Walters, the singings feature four parts - the treble, bass, lead and alto.

"The chairs are set up in a square, and each side of the square is a different voice section," Walter said. "Whoever is leading the song, so the person who's conducting everything and sometimes calling out pitches, they'll sing lead and conduct so we're on time and everything."

According to Weinstein and the students, including Denise Benson, the singings are inclusive and facilitate a participatory envinronment, with a new person leading each time.

"They're very into fostering people and nurturing them," Weinstein said. "Darian got up and stood next to 'Cousin June.'"

"(June Smathers Jolley) was like, 'We do it for the younguns. You should come up and do a song with me,'" Darian Smathers said. "She led it, and pitched it, and I just kind of stood there and shook the whole time."

"The whole point of the singings is to be accessible for everybody," Benson said.

As the tradition becomes less common, Weinstein and the students recognize the importance of ensuring it doesn't die.

"It's more fragile, I think. It's slowly dying," Smathers said.

"At the same time, there is some outreach," Walters said. "When we were at the Singing on the River, there were some people who just came in because they were interested. Granted, it was a few older folks, but still, garnering interest from some people (was nice).

"There are groups that still sing across the South and the Northeast, including some in Vermont, Maine and Massachusetts."

The tradition's older demographic makes passing down the knowledge added importance, according to Weinstein.

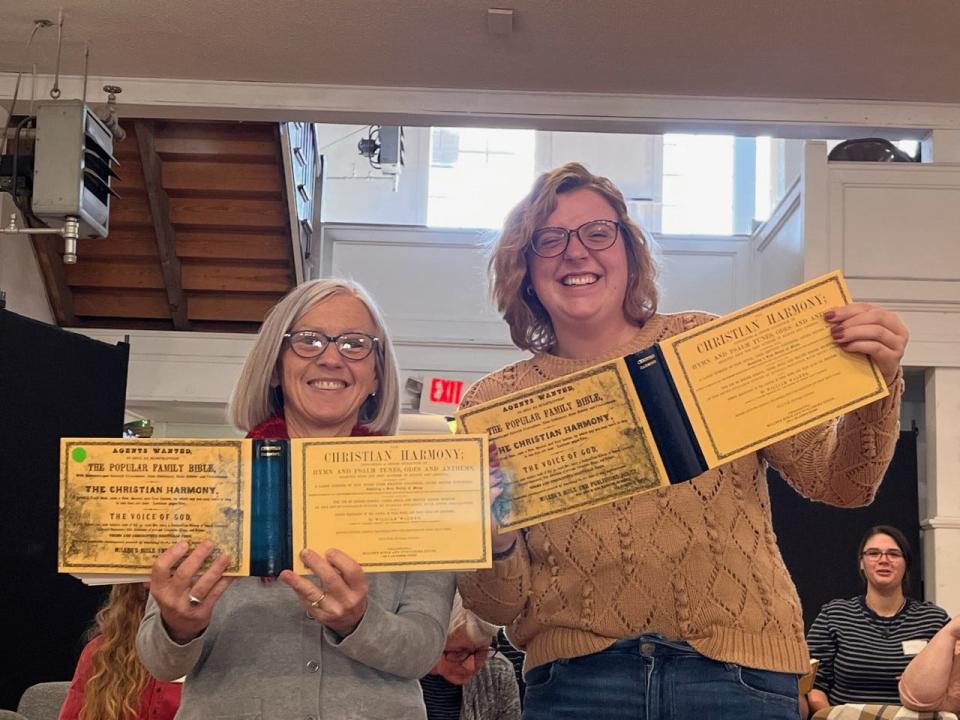

The class interviewed Zack Allen, who published a reprint of "Christian Harmony." On that day, Allen even gifted each student with a copy of the book, so that years from now, gatherings like Singing on the River can still take place.

"Everyone has their own hymnal now," Weinstein said.

This article originally appeared on Asheville Citizen Times: Mars Hill Univ. students on shape note singing: 'ancient and emotional'