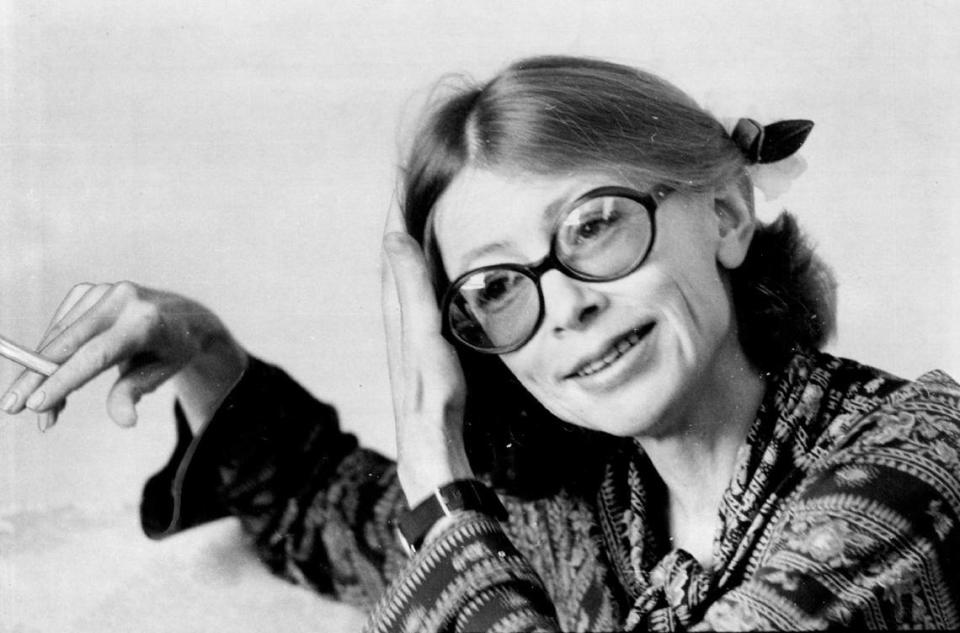

How the literary legend Joan Didion got her start on a Sacramento high school paper

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The yellowed copies of the McClatchy Prospector sat in Dea Lee Harrison’s home near downtown Berkeley, untouched for maybe 20 years.

Harrison saved these issues of the C.K. McClatchy High School paper, from the fall of 1951 and early 1952, as a memento of her time on staff. Historically, the issues hold some value, thanks to a future literary legend who also wrote for the paper then, Joan Didion.

“She was interested in things that most high school kids aren’t interested in,” said Harrison, 88, who succeeded Didion as editor of the paper under her maiden name, Dea Lee VanderBoom.

Didion, who died in December 2021 at 87, attracted no shortage of attention in her celebrated writing career, which spanned decades, included a 2005 National Book Award for “The Year of Magical Thinking,” and took her around the globe. But it all started in Sacramento, with some of the unique approach and acerbic voice that won Didion such acclaim evident in some of her earliest bylines.

Early signs of greatness

Almost 70 years on, it’s a wonder Didion got her final column for the Prospector past the paper’s censor in those days, longtime principal Samuel Pepper.

Pepper, who had a 25-year stint as McClatchy’s founding principal, generally kept students from writing anything controversial, according to Harrison. Still, Didion had a bylined column on Jan. 25, 1952, noting her generation’s indifference to being drafted into the Korean War, which by then had been underway for more than 18 months.

“It is inevitable, inescapable,” Didion wrote. “But there are no heroics about it. Everyone admits freely that they have no burning desire to go; that they will keep out of it as long as possible.”

David L. Ulin, a University of Southern California professor who has edited two books of Didion essays, read this column for the first time during the reporting of this story and immediately noted that hallmarks of Didion’s style were already evident in her high school writing.

“The voice is there,” Ulin said. “The sensibility is there. Like a lot of the key things I love about her, that sort of little bit of world-weariness, a little bit of despair or resignation or whatever it is... it’s already in place. It’s kind of fascinating.”

Joan Haug-West, an 87-year South Land Park resident, was, like Harrison, in Girl Scouts with Didion. She also shared an English class with Didion at McClatchy where the teacher had them read papers in front of their peers.

“I remember at the time thinking what a brilliant writer she was,” Haug-West said. “Maybe there was a little bit of envy there possibly.”

Didion didn’t always believe in her own prowess, though; she was famously self-critical in her professional work. And this extended to her time at McClatchy.

Washington Post national editor Matea Gold, who graduated from McClatchy in 1992, heard the piece of lore that longtime Prospector adviser Nereida Skelton, who arrived after Didion, would tell her students: How Didion would throw stories she wrote in the trash, thinking them no good, only for someone else to fish them out.

“I have no idea if it was apocryphal or not, but just the idea that Joan Didion had actually walked in those halls before and written for the Prospector was something that felt sort of like a bridge to another world,” Gold said.

Skelton, who died in 2012 at 68, kept a morgue of old Prospectors in the class during her time as adviser, including issues from Didion’s tenure. Skeleton’s husband, longtime Los Angeles Times columnist George Skelton had met Didion multiple times, in part because their daughters knew one another. Didion even attended the funeral for Skelton’s first wife, former Sacramento Bee political writer Nancy Skelton who died in 1985.

Issues of the Prospector from Didion’s era are preserved in McClatchy’s school library, but otherwise not widely available.

The issues are not in the Sacramento Room at Central Library, the Center for Sacramento History on Richards Boulevard, or the California State Library downtown. The Bancroft Library at UC Berkeley, which has a collection of Didion’s papers, doesn’t have any issues of the Prospector, according to a representative.

Paul Bogaards, a spokesperson for Didion’s literary trust, said via email that Didion’s mother preserved some of her daughter’s clippings and photos from her student days and that this material “will be available reasonably soon when a permanent repository catalogues it.”

In her time at McClatchy, Didion crossed paths with another person destined for lofty heights, Supreme Court Justice Emeritus Anthony Kennedy, younger brother of her best friend Nancy, who isn’t known to have been on the Prospector’s staff. At Didion’s memorial service on Sept. 21, 2022, the retired justice eulogized Didion as a frequent guest at the Kennedy family home.

Much of Didion’s time at the house, Kennedy noted, was spent editing her articles for the Prospector and class essays.

“She and my sister Nancy would talk about themes that Joan had in mind,” Kennedy said in his eulogy. “Then Joan would think and write and think and write all over again and think and write all over again.”

Reached by phone at his Washington, D.C.-area home, Kennedy declined to speak at length because he has a forthcoming book that discusses Didion. However, he offered a few words on the value of growing up in Land Park and attending McClatchy, saying, “It was a community that was very close together and valued traditional things.”

By the time Didion became editor of the Prospector in September 1951, she already had at least one professional clip under her belt. She began a column in The Bee from Aug. 18 of that year by praising the dancing for Music Circus of Carol Bennetts, a Sacramento High School student and reputedly the sister of one of her friends.

Didion would graduate in June 1952 at a time when McClatchy also graduated a fall class. She was introduced in the June 8, 1951 issue of the Prospector as the incoming editor for that fall.

“’Private Lives’ was a play starring Tallulah Bankhead and Donald Cook, with one of the cleanest second acts we’ve ever seen,” Didion wrote in a column in that issue. “However, this is immaterial. The point we’re getting at is – there are no more private lives at McClatchy.”

An article under the byline Mary-Margaret Didion appeared in the Sept. 28, 1951 issue of The Prospector. Harrison suspects this was Joan Didion, saying she didn’t remember a Mary-Margaret Didion.

“The new sophomores are not the shrinking-violet types one has a right to expect,” Mary-Margaret wrote. “We have tried again and again to give them that bored, blase senior stare, but they just stare right back at us. Rather disconcerting.”

On Oct. 26, 1951, Didion noted that ukeleles were “a thing of the past once more,” with only a handful seen around school since the beginning of the term. “Even these diehards aren’t bothering to learn any new songs,” Didion wrote. “They, too, recognize the end of an era.”

Though Didion was editor of The Prospector during a relatively calm period in terms of news and controversy, fellow National Book Award winner William T. Vollmann, who has lived in Land Park for more than 30 years, noted that tranquil times can prove a writer’s aptitude for storytelling.

“If we as writers can not find something interesting about our surroundings, then we have failed,” Vollmann told The Bee. “Because that’s our job, to be perceivers and to maybe amplify something that people might have missed or to create patterns or play with patterns.”

‘A small place in the sun’

In her final column for The Prospector on Jan. 25, 1952, Didion wrote, “All anyone wants out of life is the chance to live it our own way. A very small place in the sun.”

After McClatchy, Didion went on to UC Berkeley where she continued to write, moving after graduation to New York to work in magazines. She took a sabbatical to write her first novel, “Run River,” which is set in Sacramento. She found greater success in writing books like “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” “The White Album,” and “Where I Was From” and collaborating with her husband John Gregory Dunne to write screenplays such as “A Star is Born.”

“Everyone in Sacramento should read her works,” Gold said. “Because I do feel like it helps you understand a little bit about where the city is coming from and where it was at one point.

Others on the fall 1951 Prospector staff had more modest professional lives, with many of the girls growing up to fulfill roles typical of women in that era.

Beverly Kaminsky, who served as Page 1 editor of The Prospector under Didion and who Harrison remembered as being a formidable student, went to Stanford. “She wanted to go to medical school, but it wasn’t really an option,” her son Jeffrey Michel of Austin, Texas said.

Instead, Kaminsky married her high school sweetheart, future NASA astronaut Curt Michel, and was a stay-at-home mom and, later, a teacher, before dying in 1985 at 50.

Page 2 Editor Jennie Lee Clifton later settled in the Portland area with her husband Ray Brown, where they helped revitalize the congregation at St. David of Wales Episcopal Church. The Browns had four children and were married for about 64 years before dying within a few weeks of one another around the beginning of 2017.

Harrison, the Page 3 editor under Didion, also studied at UC Berkeley. She later worked as an administrator for two state agencies.

The fall 1951 Prospector staff included staff writer Lee Craddock, who later became a nurse and raised three daughters. A Black woman, she persevered through a divorce to raise her daughters as a single mother. Later known as Lee Cassidy, she died in 2008. “Mom did what she said she was going to do,” said daughter Laurel Allen-Thomas, who splits time between Oakland and Albany, New York.

One of the paper’s circulation managers, Lela Regalado, later became known as Lela Robb. Married for over 60 years to her husband Don Robb, she did office work for his swimming pool contracting business and later worked as a paralegal, according to daughter Terry Kociemba of Citrus Heights. Lela Robb died in 2019.

Then there was one of the Prospector’s advertising managers that fall, Mary Ann Dyer, who is now 88, goes by Ann Dingley, and lives in Carmel, Indiana.

Dingley, who didn’t remember working with Didion, said she dreamed of traveling when she was young. She married a Korean War veteran, had four children, and pushed her travel dreams aside. After her husband died in 2000, she finally got to travel. She counts Paris and London among her favorite destinations.

High school newspapers are crossroads. For every Didion, there are countless students who might never write professionally. But to Ulin, even if a writer isn’t born great, that’s no problem.

“I think it’s always worth it to pursue it no matter what,” Ulin said. “Because as Kurt Vonnegut, another great hero of mine once said, ‘The way that we create our souls is by making art.’”