Literate Matters: Debut novel captures small town lives

Seems there’s little reason for any of the characters in Michelle Webster Hein’s new novel to stay in Esau, Michigan.

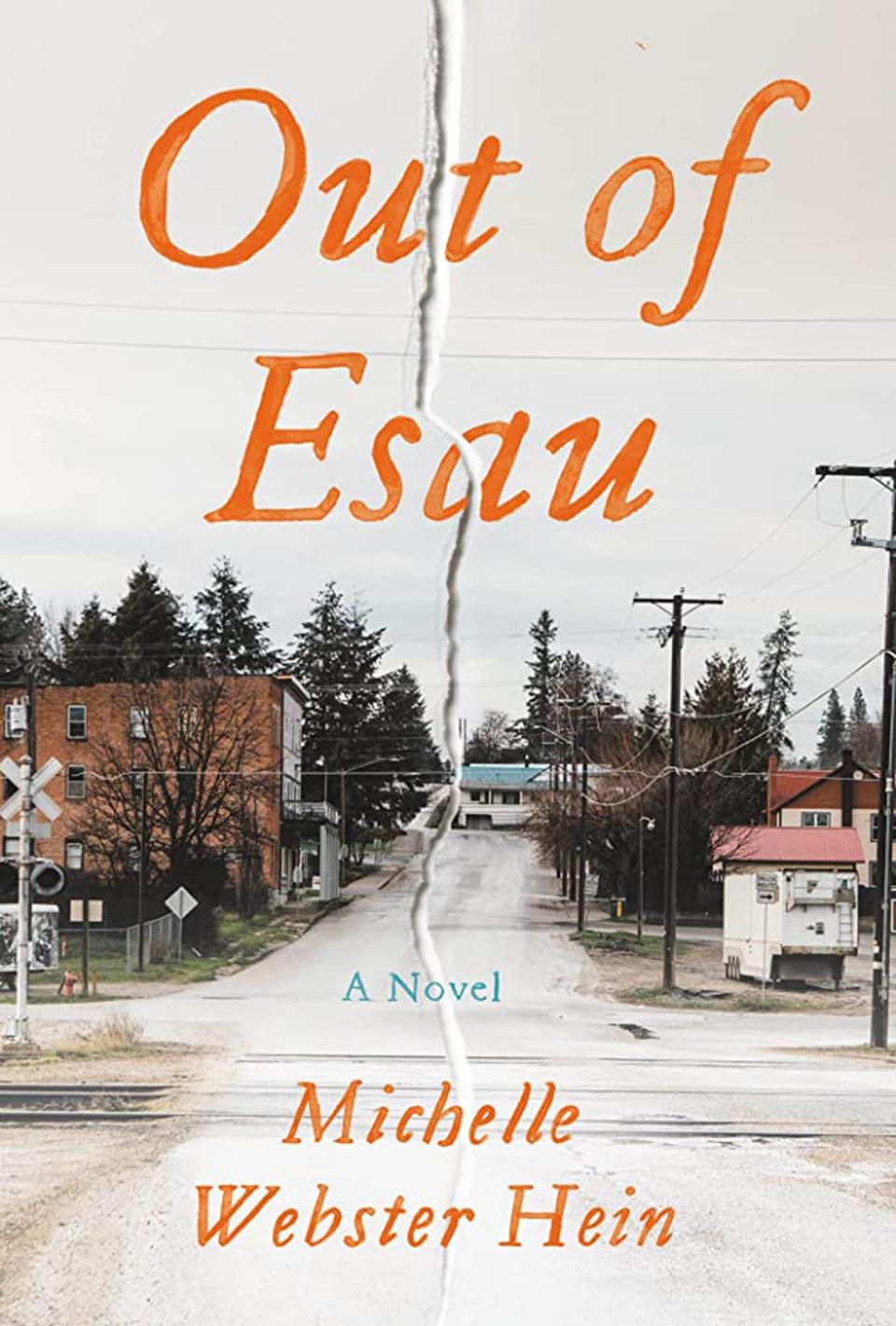

A backwater made of a “mixture of quaint and eerie, alive and dead,” a place “haunted by a livelier past” but which now feels for most “like a dead end,” it’s the setting for Webster Hein’s debut “Out of Esau,” published by Counterpoint.

Because of the limited prospects, and the echo of other failures, plenty of characters angle to leave. Like Susan, mother of Lukas and Willa and wife of Randy, who works “to protect her children from the world and from their father, to manufacture happy memories out of thin air.”

And while Randy can’t see far enough to understand leaving, he too comes to understand that abandoning his old self might be the only way to salvage his marriage.

Subscribe: Check out our offers and read the local news that matters to you

Stung by the disappointment of community college failure, Susan and Randy fell into a rhythm. Susan spends days caring for the children and maintaining the house, while Randy begrudgingly trudges off to an assembly line job that keeps them all afloat, if barely.

Both watch helplessly as their marriage craters, their sensibilities too unevenly matched. “Once, shortly after they’d married, she observed how the clouds gathered around the sun when it set–the sun’s deathbed, that’s what she’d called it–and he’d turned toward her with a look of such contempt that she’d since removed all metaphors from her conversation.”

As well, Susan understood how “exhaustion and bad judgment and all the potholes in the road of life shook down the compelling figures and left two disappointing humans slumped in the dust.”

In Pastor Robert, though, she imagines again a life of metaphor, though her attendance at Esau Baptist is less about faith than about the fact she longs for something more than pinching pennies and mending clothes. They both understand this unlikely friendship may prove untenable, but Robert recognizes “the harder he tried not to think of Susan, the more he did,” a realization she understands instinctively.

Robert’s lingering damage comes from a youth spent in foster care, though his pastoring provides a refuge until he becomes again unmoored when his mother Leotie, her health diminished, washes up on his doorstep and the two attempt to reconcile.

Webster Hein’s story unfolds through Susan, Robert and Willa, all three charged by the hope of better as well as heartache of what is and what was. Susan keeps her finger in the dike, cobbling together meals from scraps, mending torn clothing, putting on a cheery face even in the face of Randy’s mercurial behavior, while Robert accepts his duty to his mother, and Willa hopes her fears can be forgotten if only she can do or say the right thing.

There are scant stumbles in Webster Hein’s telling, like when Robert takes too quickly to calling Leotie “Mother” after a lifetime of absence, or when the simple coincidences of small town proximity bring Susan and Robert into the same spaces in unlikely ways. But the author captures beautifully and fully the quiet desperation of all involved. She also reveals the interiority of her three main characters with attention to both space and pace. The result is a love story built in the cracks.

But as you might recall from the song, it’s the cracks where the light gets in, even in “Out of Esau.”

Good reading.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Literate Matters: Debut novel captures small town lives