Litman: Forget constitutionalism. Rand Paul's attempt to preempt Trump's trial is just brute force politics

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When it comes to Senate Republicans, the last refuge of scoundrels appears to be the Constitution, at least as it's interpreted by Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky.

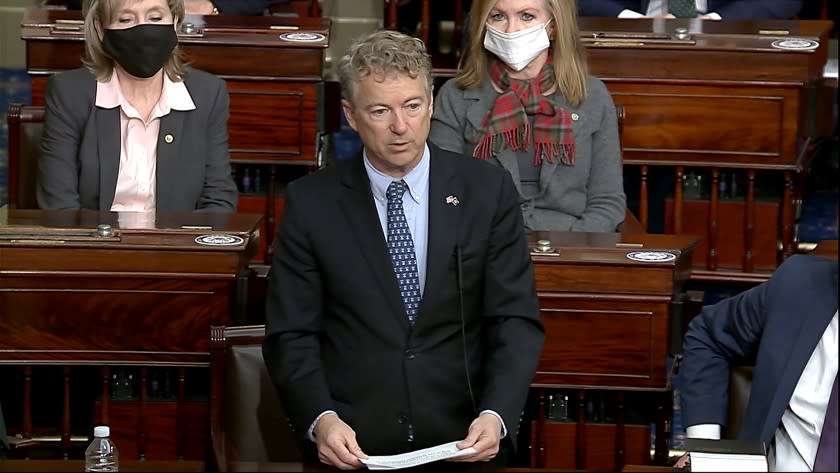

Immediately after the Senate convened as a court of impeachment for the second trial of Donald Trump, Paul raised a point of order. He wanted to preempt the whole megillah on the grounds that the Constitution forbids the trial and conviction of officials who are already out of office before an impeachment trial begins. The motion was defeated, but 45 Republicans voted for Paul’s interpretation.

It should be obvious that constitutionalism's only role for this GOP gaggle is to provide cover — very thin cover at that — for their desire to avoid having to pass judgment on former President Trump’s incitement of insurrection, as charged by the House of Representatives.

Moreover, the Republicans' objection — as they must have known — was clever but mistaken.

Paul’s point of order tried to capitalize on the seeming oddity of trying the former president now that he is the former president. “Impeachment is for removal,” Paul said, “... and the accused here has already left office.”

But it’s not so odd. What the Constitution says is that impeachment isn’t only about removal from office. Article 1, Section 3 describes the further purpose of impeachment, which is, to disqualify the official — after conviction — from ever holding federal office again.

The latest Trump trial in the Senate is as compelling a use of the two-fold impeachment power as the Senate ever has encountered. It is appropriate for the system to express its condemnation of the former president's nefarious conduct of Jan. 6, but after four years in which he so often hijacked the Constitution and took it on a joy ride, it is even more crucial to prevent him from wreaking further damage.

There is also a broader constitutional point that Paul and the 44 Republicans who joined him are missing.

Our system of government sets up rules as to who gets to decide constitutional questions, and it’s an indication of the republic’s stability that we accept the outcome as authoritative. The normal decider is the courts, especially the Supreme Court.

But the Constitution supplies a different decider for impeachment proceedings. The Supreme Court itself made that clear in the case of Nixon vs. United States. Walter Nixon was a federal judge who was sentenced to prison for perjury but declined to resign. The House impeached him, and the Senate opted to appoint a committee to take evidence and report back to the whole Senate, which convicted him. Nixon argued that the process was unconstitutional because it wasn’t a “trial,” as Article 1, Section 3 specifies, unless the Senate “jury” heard all the evidence.

The Supreme Court declined to decide the issue. Rather, it held that the language of the Constitution granted sole “authority in the Senate to determine procedures for trying an impeached official, unreviewable by the courts.”

As to the question of an impeachment trial for a former official, the Senate has already spoken; there is an established precedent. In 1876, when President Grant’s secretary of War, William W. Belknap, resigned just before he was to be impeached for corruption, the House went ahead anyway and so did a Senate trial — neither of which actions fit Paul's reasoning. (For more details, see University of Texas Law School professor Stephen Vladeck's recent essay on the precedent in the New York Times.)

Some senators in Belknap's case, like Paul today, expressed doubt about the constitutionality of trying an official who was already “removed.” But the Senate as a body nonetheless concluded that it had the power that Paul wants to argue the Constitution precludes.

It’s true that in practice nothing can stop an individual senator from substituting their judgment for the authoritative one of the full chamber. But that is not constitutionalism; it is rather brute force politics of the sort Sen. Mitch McConnell and the Republicans have practiced for five years when they were in the majority.

Tuesday's vote is a particularly outrageous maneuver, given that McConnell, while still majority leader, had closed the Senate until Jan. 19, preventing a second Trump impeachment trial from beginning while the former president was still in office.

Trump has now been charged twice by the House with the most serious misbehavior of any president in history. In the first instance, all but one of the Senate Republicans sat on their hands: They announced their judgment before the trial while refusing efforts to augment the evidentiary record. Now they are apparently prepared to hide behind the Constitution — improperly — to again avoid addressing the merits of a strong case against Trump.

If the Republican senators acquit the former president on spurious jurisdictional grounds, they will have neglected their highest duty. The country deserves a public judgment about whether Trump violated his oath of office on Jan. 6. The Constitution demands it as well.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.