On the Little Colorado River, a confluence of interests presents constant challenges

Water for the river:

Colorado River | San Pedro River | Gila River | Little Colorado River

The Little Colorado River's turquoise blue waters and the place where they comingle with the larger Colorado on its path through the Grand Canyon create a place that calls people to explore one of the Southwest's most intriguing regions.

The Confluence.

The area is held sacred by several Indigenous peoples in the region, including the Hopi, Navajo and Zuni peoples. It's also the stronghold of the humpback chub, a minnow species that has survived in the Colorado River Basin's warm-water canyons for about 3.5 million years, but whose existence is threatened by dams and invasive species.

But the Confluence is only the end of the Little Colorado and its story.

Along the 338-mile journey from high in Arizona's White Mountain Apache tribal lands to its final stretch in the Canyon, the Little Colorado has left its mark on Indigenous cultures and settler farmers seeking to wrest a living from the wind-blown mesas in northeastern Arizona. It has fed dreams of developing the Confluence into a place where masses of tourists could ride a tram to the canyon floor, and it has sparked the possibility of electric current generation within its basin. Efforts to preserve an ancient fish threatened by human activities and to maintain the river's other natural resources remain a constant struggle.

It's a story that reflects the ongoing struggle between people who see the Little Colorado's waters and landscapes as a resource to tap and those who seek to preserve it as a place of worship, quietude and rugged, untouched beauty.

Small river, big footprint

The Little Colorado, one of the U.S.'s rare north-flowing rivers, bubbles up from the ground on the eastern flank of Mt. Baldy in the White Mountains, meanders through the high mesas of eastern Arizona and the Painted Desert, and parallels the western edge of the Navajo Nation to the Confluence.

The sparkling clean water that flows down from Mt. Baldy encounters its first hurdle at Lyman Lake, just south of St. Johns. There, the Little Colorado was dammed to create a 1,500-acre irrigation reservoir.

Although it's fed by several tributaries, including the Zuni and Puerco rivers, Silver Creek and several intermittent washes, the middle section of the Little Colorado rarely flows all year long until it gouges its way from spring runoff and monsoonal storms through rock and sands to Blue Spring.

The remaining 13-mile-stretch from the springs to where it meets its larger sibling is also the river's best-known portion, the Little Colorado River Gorge.

At some places, the walls of the gorge tower 1,500 feet above the river bed. Visitors are fascinated by the rich turquoise coloration the water takes on as it washes through deposits of travertine, a variety of limestone formed from calcium carbonate. At the narrow gorge's floor, the vibrant waters sparkle against the red rocks they have exposed after millions of years and the verdant plants that line the river's edge.

'Our place of emergence'

Indigenous peoples in the Southwest hold strong ties to the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers, the Grand Canyon and the Confluence.

The waters that live underground also provide life-giving water in another direction.

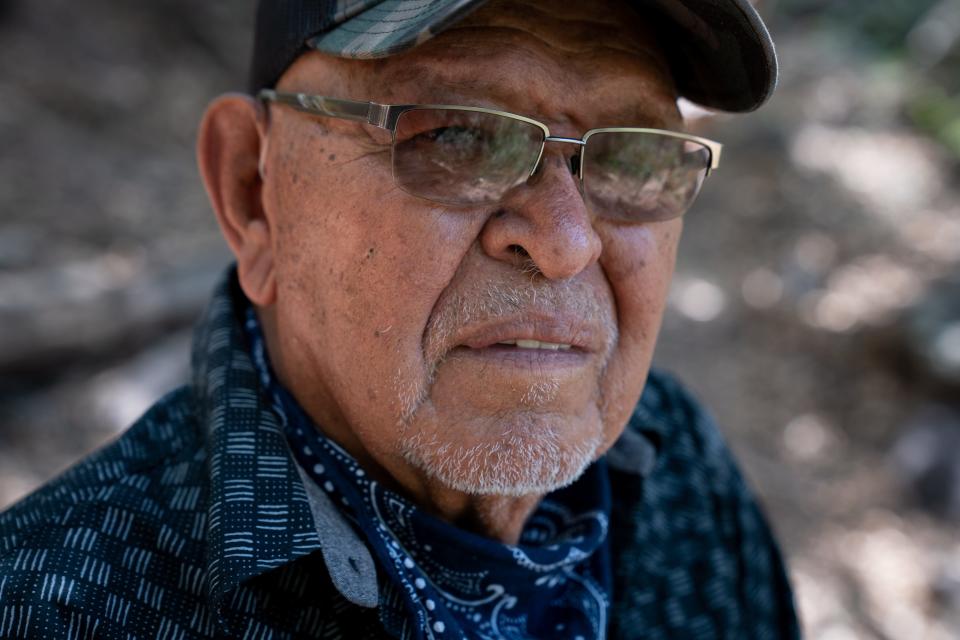

"We live on the headwaters of all the water that heads west," said Ramon Riley, cultural resource director for the White Mountain Apache Tribe. That water, he said, includes the four major reservoirs that serve central Arizona — the Roosevelt, Apache, Canyon and Saguaro reservoirs along the Salt River.

Apache elders say the rivers birthed within Mt. Baldy bring life to humans, animals, creepy crawlers and plants, Riley said. They also teach the need for Apache people to care for the mountain and the waters that lie beneath.

Close to the Confluence lie some of the Hopi Tribe's most sacred places. Sipapu, an almost perfectly round, large travertine dome and spring, is the place where the Hopi people emerged into this world. The rugged Salt Trail Canyon leads Hopis on pilgrimage and other people to salt deposits and eventually, to Sipapu. The Hopis call the Canyon Öngtupqa, or Salt Canyon.

The Canyon, or Chimik’yana’kya dey’a in the Zuni language, is also the place of emergence and beginning for the Zuni people, said Jim Enote, a Zuni tribal member and lifelong farmer.

"It is our ultimate point of reference and an essential part of our identity," Enote said.

Enote, the executive director of the Colorado Plateau Foundation and board chair of the Grand Canyon Trust, said if he followed the Zuni River, which meanders through his tribal lands in western New Mexico, it would take him to the Little Colorado River, known to Zuni people as K’yawinan A’honna or Red River and up to the Confluence.

This, Enote said, means that the Little Colorado River is like an umbilical cord connecting the Zuni people to the place where they came into existence, "like returning to our mother's womb." He likened it to other holy rivers such as the Jordan, the Columbia or the Whanganui rivers.

On Arizona's rivers: From New Zealand, Maori leaders bring Arizona tribes lessons in protecting the waters

Ancient fish threatened by dams and sport fish

The warm waters of the northernmost stretch of the Little Colorado are also the largest remaining stronghold for a fish that was almost driven to extinction by human development.

The largest population of the humpback chub, a member of the minnow family, can be found in the Little Colorado River near the Confluence. The chub have existed as a species for more than 3.5 million years, only to fall victim to human activity.

The fish, with the distinctive hump behind its head, needs water temperatures of at least 61 degrees to spawn, but Glen Canyon Dam's hydropower generation sends cold water down the Colorado's mainstem, which inhibits spawning. The chub took another hit because they are not adapted to fend off predators like rainbow and brown trout that were introduced into the river.

The chub was listed as an endangered species in 1967. After more than 50 years into a conservation and management effort, the fish was upgraded to "threatened" status in 2021.

Although the fish is no longer considered endangered, officials closely monitor its progress. David R. Van Haverbeke, a supervisory fish biologist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said the population is holding steady. Some of the chub have ventured out of the Little Colorado to take up residence below Lava Falls.

Van Haverbeke has spent decades on the canyon floor dealing with the chub and he's come to appreciate their unique appearance.

"These fish are cool if you get to know them and handle them," he said.

Invasive fish like small mouth bass and brown trout may also move closer seeking out their next meal — the chub. One solution is removal, although some tribes insist that wildlife agencies deal with the invasive species humanely.

"A long, long time ago, during an ancient journey, some of our kin became aquatic beings," Enote said. The Zuni regard those fish as relatives. "We understand and are okay with the rationale for removing the invasive fish but oppose the inhumanity of poisoning them."

Developers eye the Little Colorado River and the Confluence

In recent years, the Little Colorado River's northernmost reach and the place where its water merges with the Colorado's mainstem, have been targeted by developers. In the mid-2010s, a group of investors proposed building a resort that would have been named the Grand Canyon Escalade. The star attraction was a 1.6-mile gondola ride that would have whisked tourists from the canyon's rim down 3,200 feet to the Confluence in only 10 minutes.

Opponents of the resort formed the grassroots group Save the Confluence to fight the proposal. Other tribes with ties to the Confluence — the Hopi, Zuni and New Mexico pueblos — passed resolutions opposing the resort and the gondola. Finally, the Navajo Nation Council "slew the monster," as the Save the Confluence members described the 16-2 vote that rejected the project.

The river was also proposed as two of three sites for a proposed electric storage and generation project, which opponents say would have damaged cultural sites and humpback chub habitat.

The proposed Salt Trail Canyon and Little Colorado River projects would have used a technique called pumped hydro. Water would be stored in an upper reservoir with a hydroelectric generating station. When electric power demands spike, the upper dam would release water through the turbines, generating power that would be distributed using a substation and high-power lines, which would also have to be constructed to connect to the existing electric grid. The lower reservoir temporarily holds the water, which is then pumped back to the upper reservoir to recreate the "battery."

Residents and Save the Confluence mobilized once again to fight the developer, citing the expected damage to cultural sites, the chub and the area's ecology. In 2021, the developer altered the plans to move the project farther south, away from the Confluence and its ecological and cultural treasures. The current project would place the dams in Big Canyon, a dry wash that empties into the Little Colorado, on Navajo Nation land. That project would require pumping groundwater.

One hurdle the project faces: water to fill the reservoirs. The Navajo Nation has yet to quantify its water rights, including the groundwater developers want to use. In 2003, the nation sued for a share of the Colorado River. That case was heard on March 20 by the U.S. Supreme Court. The Navajo and Hopi tribes have also been embroiled in a decades-long adjudication to allocate Little Colorado River's waters along with 6,000 other claimants.

Other threats to the region include tourists trashing one of the river's best-known but intermittent attractions, Grand Falls, or Adah'iilíní. When monsoonal rains or spring runoff swell the usually dry riverbed south of Blue Spring, the chocolate-brown water cascades down a 185-foot cliff. But tourists have damaged cultural sites, left trash behind, accosted residents when they break down on the rough roads and generally created havoc in the area. In March, the Navajo Nation closed the area to nontribal residents.

Van Haverbeke said all players have to work together to protect often conflicting priorities for the Little Colorado and Colorado rivers.

"There are always trade-offs," he said. "Culture, vegetation, water, beaches and power generation make it difficult to come to an optimum solution for everything." But, Van Haverbeke said, everybody tries to do the best they can to work together, coordinate and collaborate.

Back at the headwaters, Riley said one of his tribe's biggest issues is maintaining pure, clean water for the rivers that are birthed in its land, including the Little Colorado. In the old days, Riley said, Apache people tried to protest what was happening to their lands and waters but didn't speak English.

"So we learned English and started to fight back." He said Native people were at the forefront of fighting for laws like the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act and environmental protection laws.

Indigenous peoples, environmentalists and their allies will continue their labors to preserve the Little Colorado River.

"Protecting the confluence is protecting part of the history of the human experience," Enote said. "It is a fragile place, and there is no place that can substitute for it."

Tribes and water: Arizona tribes wait for water as settlements languish in courtrooms and bureaucracy

Debra Krol reports on Indigenous communities at the confluence of climate, culture and commerce in Arizona and the Intermountain West. Reach Krol at debra.krol@azcentral.com. Follow her on Twitter at @debkrol.

Coverage of Indigenous issues at the intersection of climate, culture and commerce is supported by the Catena Foundation.

My articles are free to read, but your subscriptions support more local reporting that holds governments and other entities to account. Please consider a subscription to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Little Colorado River are key Indigenous cultures, fish