Little help for a million Californians on wells in historic drought

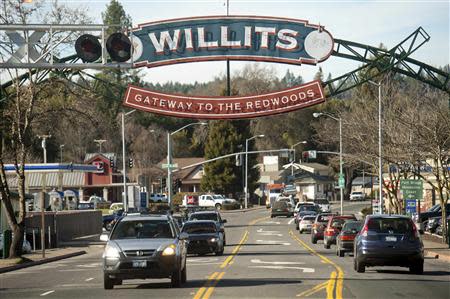

By Sharon Bernstein FORT BRAGG, California (Reuters) - Michael Holmes got by at his rural home near California's rugged northern coast on a disability pension and water from a decades-old well -- until the well dried up. Holmes, 65, is among an estimated million Californians who rely on private wells, many now threatened by the state's historic dry spell and with no direct access to a multi-million dollar state drought relief program. "When this place was built in the 1950s, the water was three feet below the ground," Holmes said, pointing a flashlight down the well's long, empty shaft. "Now, the pump is down 26 feet and we're still running out." These days, Holmes buys drinking water by the gallon and waits until enough water gathers to take a shower once a week. The pump hangs an inch off the ground at the bottom of his well, and when the water comes up, it's full of muck and minerals. "It turns my white hair yellow," Holmes said, tilting his head down to show. California is still counting the number of threatened wells, in the latest sign of how the state is struggling to address and even understand the extent of the worst drought in decades. A state report released last week showed groundwater levels in California had dropped over the past three, dry years, but focused mostly on issues faced by municipal water systems and agriculture, not well-dependent homeowners. Governor Jerry Brown declared an emergency in January in the most populous U.S. state, requesting voluntary conservation efforts, funneling millions of dollars to farmers and municipalities, and even providing funds to help farm workers idled by the drought buy food and pay rent. In a state where the lack of water for irrigation threatens a half-million acres of farmland, and a rapidly shrinking snow pack means less drinking water for nearly 40 million people, help was rushed to those who live within the boundaries of even the smallest municipal water districts. Even fish got help. As river waters receded, the state trucked 30 million hatchling salmon, a record, to ease their annual migration. The $687 million drought relief package of grants, loans and other financial assistance programs to fund solutions such as water storage and recycling projects, anti-contamination efforts and emergency water supplies, was aimed at communities in need. But the relief plan did not include funds targeted at helping those relying on private wells to dig deeper or make other improvements. They are not considered part of the public delivery system, and finding relief for them is more complicated, said Debbie Davis, the governor's drought liaison to counties. Oversight of water systems in California is limited and fractured. Counties are responsible for oversight of private wells, she added, and it wasn't until homeowners started calling a drought hotline in Mendocino County seeking help that state officials realized there was an extensive problem. "For the most part, domestic well users are expected to be responsible for their own resource," said Davis, who estimated a million people depended on wells. A working group is tracking down well owners and assessing needs, said California Natural Resources Agency spokesman Richard Stapler. About 10 miles south of Holmes's home in Ft. Bragg, many wells are going dry in the tiny beachside village of Mendocino, whose 900 residents rely entirely on private wells, said Roger Schwartz, president of the village's tiny water district. One woman in Mendocino County called the drought hotline to say she needed water to bathe her disabled husband, who was incontinent, said Brandon Merritt, a county analyst. Another family said it could not afford the $350 a private dealer was charging for a month-long supply of water. Schwartz, of the Mendocino Community Services District, has pushed the state to offer grants or loans to help residents purchase water or dig deeper wells. But Davis said the state will focus first on helping those who can be hooked up to existing water systems. Such efforts would likely not help Arthur "Mark" Fontaine and his wife Ellen. They estimate it would cost $20,000 to improve the well that serves their property, which lies four miles from the nearest town and is likely too far away to be hooked up to municipal water. Since October, they have been buying water from a broker. "We've always had to conserve here," said Ellen Fontaine, who grew up on the property, about 24 miles from Willits. "But I have not been able to do laundry here for almost two months." (Reporting by Sharon Bernstein; Editing by Cynthia Johnston and Peter Henderson)