‘It’s a little scary’: How $1M homes are changing Kansas City’s Hispanic West Side

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

High on the bluffs of Kansas City’s West Side, Monique Ortiz stepped out onto the porch of her 120-year-old home and, with a mixture of uncertainty and sad acceptance, looked across the street at the future.

“It’s a little scary,” she said. “I just hope we get good neighbors.”

On this April day, workers hoisted plywood panels to a frame of two-by-fours. The snap of nail guns cracked the air. At Mercier and 18th streets, a hydraulic jackhammer pounded through a limestone ledge.

In the next few months on this block, seven contemporary town homes — slender, built shoulder-to-shoulder and priced by Lambie Homes at $494,000 for 1,400 square feet — are rising on empty lots across from Ortiz.

Five more homes, each costing about $600,000, are being built alongside her by New Line Homes.

That does not include the $800,000 towering house with an elevator and bocce ball court that went up in 2019. Next to it are three empty lots soon to be developed by Edward Franklin Building Co., a high-end firm whose multiple West Side properties include side-by-side $1.2 million homes a few streets away.

Total count: 16 new houses on one block.

“These houses don’t look like anything in the neighborhood,” noted Ortiz, 40, a third-generation West Side resident who, with her Navy veteran husband, Manuel, is raising their four children there. “It’s like one world is here and, across the street, is another. It changes the culture.”

It’s precisely that cultural change that has many longtime West Side residents worried.

Their concern is existential. They fear that given the pace of gentrification — with ever more magazine-worthy homes raising property taxes — with lap pools, waterfalls and sweeping rooftop views of the downtown skyline — the West Side’s Hispanic population will gradually vanish, becoming Hispanic in name only.

A new real estate tax structure signed into law last year is designed to help stem that change, at least for awhile. Century-old community stakeholders, like the Gaudalupe Centers and Mattie Rhodes Center, also insist that as long as they are around the neighborhood’s Hispanic influence will remain.

“I tell people every day, we will never physically leave this neighborhood,” said Beto Lopez, CEO of Guadalupe, which is preparing for its annual Cinco de Mayo Community Fiesta on Friday and Saturday.

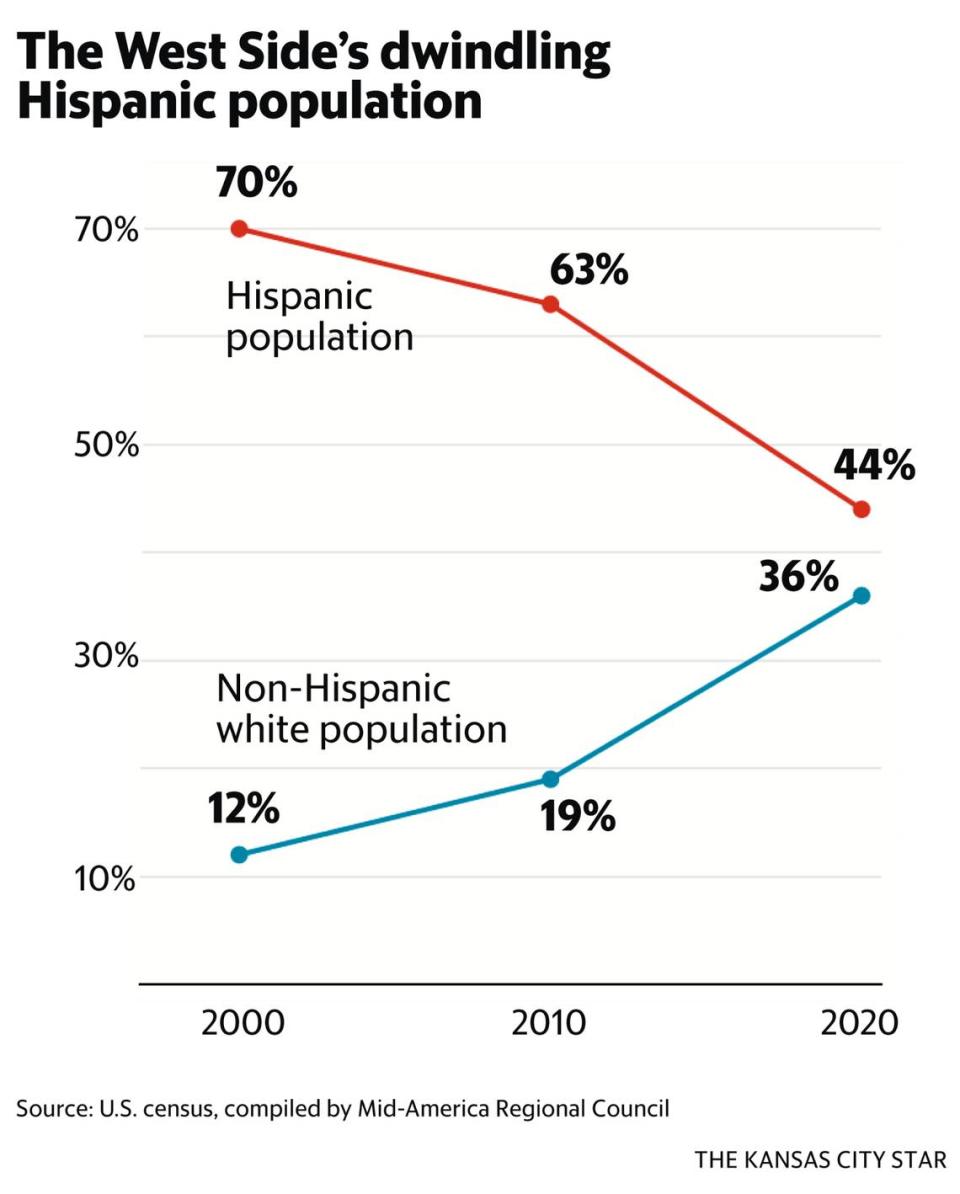

But U.S. census figures also speak to the trend.

Back in 2000, 70% of West Side residents were Hispanic. In 2020, the number slid to 44%, meaning that already, the Hispanic West Side is no longer majority Hispanic.

Over many years, longtime West Siders have dispersed to the suburbs. For newer Hispanic immigrants, home has become Wyandotte County (33% Hispanic) or Kansas City’s Northeast area along Independence Avenue.

On the West Side, meanwhile, the percentage of non-Hispanic white residents since 2000 has tripled to 36%.

“As Hispanics, we cannot afford to live here anymore,” said Augustin “Gus” Juarez, 53, who grew up in the neighborhood and who, for 22 years, has owned Los Alamos Cocina at 17th and Summit streets. “I tell people, you have $1 million, you can do what you want.”

Lap pools and legacies

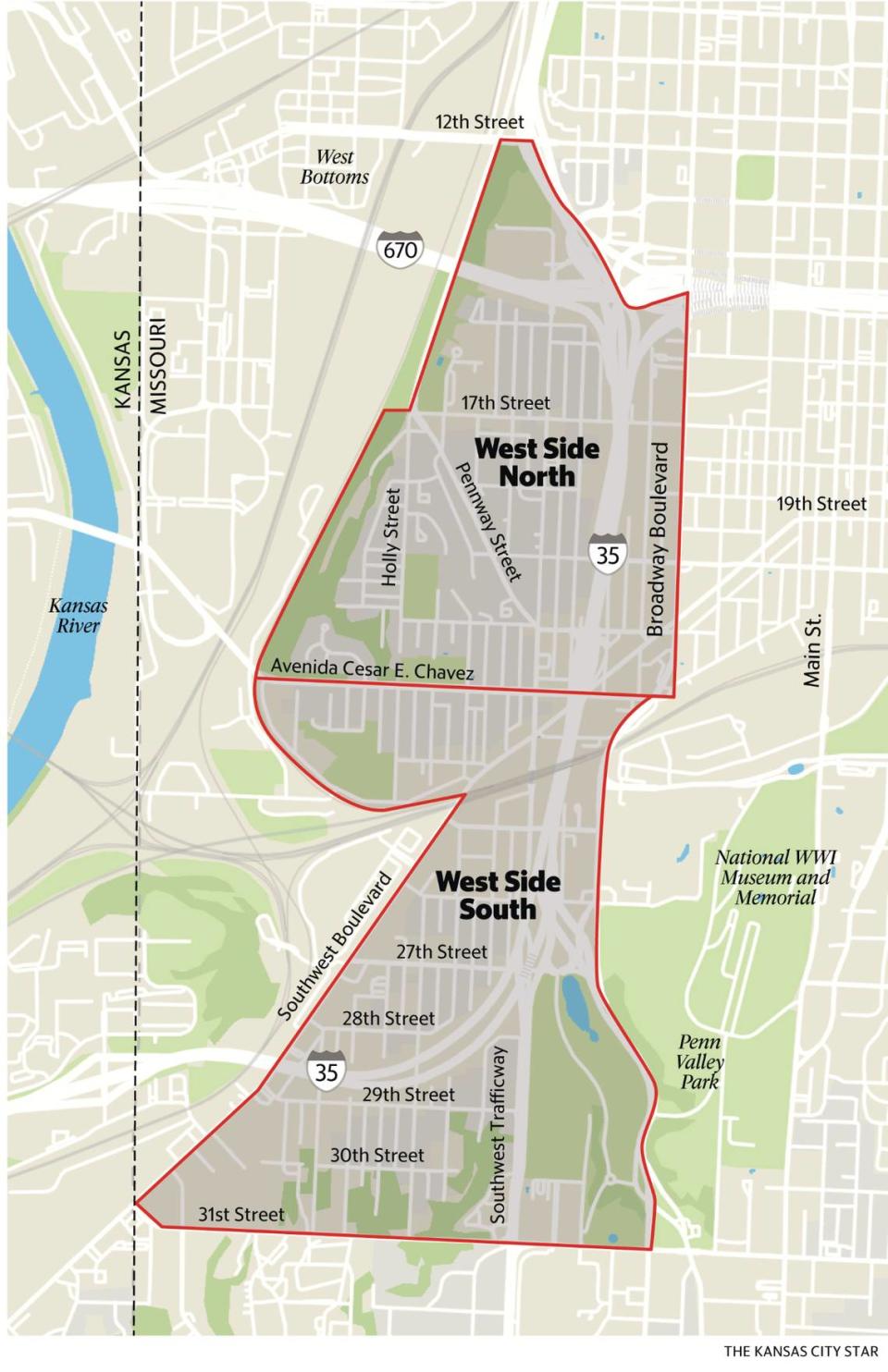

About 3,500 people live on the West Side. Populated first by Irish, Germans and Swedes, the neighborhood west of downtown became home to Mexican immigrants who, in the early 1900s, traveled north during the Mexican Revolution to find work on the railroads and in the slaughterhouses of the West Bottoms.

Generations of descendants cling to that legacy.

“I’m 74. I’ve been here all my life,” Tony Castaneda, third-generation in the neighborhood, said from his bungalow, now in the shadow of two towering new homes. His grandfather, a crop grower in Mexico, worked his lifetime at the rail yards. “He walked every day up and down that hill. Every day.”

The West Side is a distinctive neighborhood of mixed — many say “eclectic” — housing and people who span the economic spectrum. Fully one-third live below the poverty line, many in aging bungalows 100 years old or more.

Lined with Mexican restaurants such La Posada, Le Fonda and El Patron and businesses like the Roasterie and Boulevard Brewing Co., Southwest Boulevard cuts the neighborhood in half. Sacred Heart church sits to the south; Our Lady of Guadalupe to the north.

Along and atop the hill near 17th and Summit streets, some 30-plus years of slow and now accelerating gentrification — begun in the late 1980s by baby boomer artists — has turned it into what may be the closest area Kansas City has to a San Francisco enclave, a hillside mix of wealth and hipster trendiness.

Shops and restaurants that include the Blue Bird Bistro, Clay & Fire, The Westside Local, Yoli Tortilleria (a James Beard finalist this year for outstanding bakery) anchor streets where bungalows mix with renovated Victorians and cubist and A-frame contemporary homes with prices ranging from $700,000 to more than $1 million.

Sporting KC’s Graham Zusi bought an $882,000 home up the hill in 2019. Bill Lyons, the former president of American Century Investments, bought his 5,000-square-foot house there in 2013 with his wife, Peggy, for $685,000. Zillow now prices it at more than $1.1 million. John McDonald, the founder of Boulevard Brewing Co., owns an 1880s home there. So does Adam Jones, an early developer of the West Bottoms.

“We loved the view. … We’re urban dwellers,” said Mary Zahner, 70, who with her husband, Tom Kramer (both Ph.D. psychologists) moved up from Florida to take residence in a wing-shaped home recently finished on Jefferson Street. It has a lap pool and panoramic view of downtown through floor-to-ceiling windows.

Zahner, who had been away from Kansas City for 50 years, is a member of the Zahner Co. family, metal fabricators based in Kansas City for more than 100 years. Her brother Tom, the company’s chief operating officer, is building his own modern home two parcels away.

“We had no intention of moving,” said Zahner, who conceded to being largely unfamiliar with the West Side’s history. “My brother said, ‘Oh, you’ve got to look at this house.’ So we just happened to make an appointment. … We thought, ‘Oh, my gosh. This is beautiful.’”

When Kim and Jeff Armstrong moved into their new home in 2021 — Zillow prices their gray-black cubist house at $857,000 — one of their prime intents was not to change the character of the neighborhood. Their stretch of Madison Avenue had already become a mix of old and new. They purposely built on an empty lot.

“We didn’t push anybody out,” Armstrong said. “When we lived in Fairway, one of the things that was disappointing was how many people would say, ‘Gosh, this is such a charming neighborhood. We really would love to live here. Let’s buy one of these houses, tear it down, and build a 5,000-square-foot home that doesn’t have any charm and doesn’t fit into the neighborhood.’

“It was where you’re kind of ruining what you bought there for.”

‘Three garages?!’

While only a few West Side residents possess panoramic views, tons possess sweeping and often conflicting viewpoints on how it’s changed. Voices range from developers to luxury homeowners, from lifelong Hispanic residents to community stakeholders to business owners.

Pedro Zamora, executive director of the Hispanic Economic Development Corp., sees a threat in West Side gentrification — accompanied by skyrocketing property taxes and what he called “rapacious” developers. He blames policies that he says push luxury over affordable housing, rich over the working class and poor.

Faced in 2019 with tax hikes averaging 128% — some rose 400% — many West Side residents struggled to pay bills, stay in their homes, or felt forced to move.

“It’s a problem. It’s a big problem,” Zamora said. “I think as you build those homes, you displace moderate to low-income housing.” At his most incendiary, he said, “I call it ethnic cleansing.”

Jerry and Anna Roseburrough, lifelong West Siders, sat on the front porch of their house at 27th and Jarboe, a bungalow they bought some 50 years ago for $2,800. Anna, the vice president of the Sacred Heart Neighborhood Association, is of Mexican heritage. Jerry is of German. They met and fell in love working at Macy’s downtown.

“I grew up, got married, and moved three feet north,” Jerry said, and pointed next door. The house once belonged to his parents. His late sister lived down the street. His daughter still does.

“My mom and dad said that the only way they wanted to leave their house is feet first,” Jerry said. “And that’s how they left. They died in that house and they took them out feet first.”

The Roseburroughs said they expect to go the same way, although it may be in a changed landscape. Luxury apartments fill downtown and the Crossroads. These days, when the couple look atop Signal Hill in the southern reaches of their neighborhood, they see 48 shipping container studio apartments staring down at them — tiny at 360-square-feet each and renting for $1,000 a month.

The Roseburroughs see what’s happening: old West Side resident dying, their kids or grandkids who live in the suburbs selling off their tiny homes or empty lots, developers snapping them up at a song to build anew.

“I think our time over here is numbered,” Jerry said, blaming city and other leaders for so long neglecting the West Side, setting it up for easy sale.

“I think they’ll flatten us out,” Anna said.

“They’ll come in here and build apartments,” her husband predicted. “You see apartments going up everywhere.”

At 23rd and Jarboe streets, 63-year-old Rosario Coronado-Castaneda’s eyes filled with tears, her voice choked with emotion as she talked about the “monstrosities.”

Coronado-Castaneda grew up in her house. All her life, she could crack open the back kitchen door, or step into her backyard, and see the tower of Our Lady of Guadalupe church on Avenida Cesar E. Chavez. She could hear its bells.

But this year, just one street away, sits a new, four-bedroom, three-and-a-half bath cubist home on Belleview Avenue that is nearly twice the height of its neighboring bungalows and blocks Coronado-Castaneda’s church view. And the sound.

“I can barely hear the bells anymore,” she said.

Across and up the street from her is a second modern house that is equally tall, built on four lots that had been empty for decades.

“As it was growing, as it was building, we were like, ‘This thing has three garages?!’ We could do nothing to stop it,” Coronado-Castaneda said. “If you want to be part of the neighborhood, then why the monstrosity? You had to have known when you were doing the plan that this was not going to fit in.”

Except Barb Johnson does want to fit in.

Age 66, a former teacher for 29 years, she and her husband built the home that blocks Coronado-Castaneda’s view. The other tall house belongs to her married son.

“My son wanted to move down here,” Johnson said. “His wife is from Brazil and is used to living city life. So they built their dream house here. When he bought, I said, ‘OK, do you mind if I live a block away from my grandson?’”

So the Johnsons, who lived 39 years in Raytown, paid $150,000 for three parcels, two of which included small, empty and — vital to the couple — dilapidated houses, which they razed.

“We didn’t want to displace neighbors,” Johnson said. “The houses that were here: One had been filled with vagrants and everything else and had been empty for a long time. The other little one here had been empty for 20 years.”

An aunt had left it to a niece who was more than happy to sell, Johnson said.

“Both houses,” she said, “were unfixable.”

Beyond having her son a block away, Johnson said she and her husband loved that so many of the homes around them belong to Hispanic owners whose aunts, uncles, cousins, brothers, sisters and sometimes children live nearby. In designing their house, she said, they purposely included a welcoming front porch to fit in with others.

“We want to be part of the neighborhood, not change the neighborhood,” Johnson said. “I don’t want people to come in and think, ‘Well, we don’t like this. This should change.’

“No. You’re moving into their neighborhood. You fit into theirs.”

That sentiment sounds great, said Navid Jones on nearby Holly Street. Except he thinks it’s hogwash.

“They’re doing it like overlords,” he said. “’I want to be part of the neighborhood. But I’m going to tear down houses that have been here for 100 years — your grandmothers’, aunts’ and neighbors’ houses — and I’m going to build a four-story house and a giant garage. I want to be part of the neighborhood, but I’m going to do it by whacking half the block down.’

“It doesn’t make sense.”

Jones, 32, was raised at 17th and Summit. His parents, Adam and Noori Jones, own at least eight properties on the West Side. The bungalow he’s fixing up on Holly was built in 1890.

He maintains that while it may have made sense decades ago to demolish houses deemed blighted or unusable, that no longer is the case.

“Now the area is valuable,” he said. “They 100% could fix them up. They just don’t know how, or they say, ‘Oh, it’s a piece of s****, or it’s falling over. So I’m going to tear it down to build a house that you’d build at, like, 95th and Mission in Johnson County.’

“I mean every person is coming here thinking they can take advantage of the situation.”

Blowback

Developers hear the criticism loud and clear.

Their view is that they are not trying to take advantage of anyone, let alone erode the Hispanic culture that, for buyers tired of suburban sameness, is part of the West Side’s appeal. That, plus skyline views, plus downtown proximity. Together, they have created a market, which only exists because people, often Hispanic people, are willing to sell their lots or houses.

Even some longtime West Siders are sympathetic to that view.

“These people who gripe about gentrification: Don’t sell,” said Ron Estevez, 70, living in the house his family has owned since the early 1900s. “We get stuff in the mail all the time: ‘We’ll pay cash for your house.’ Don’t sell.”

The arguments favoring gentrification are well known: It’s good for languishing neighborhoods, bringing vitality; good for homeowners, who see rising property values; good for cities, who get more taxes; good for local businesses, who attract customers.

Anne and Greg Rothers, owners of the New Line Homes company, nevertheless understand the neighborhood nervousness.

“This is a deep, rich, family heritage area. There are forces at play,” said Anne, standing on Mercier Street where five of their 1,800-square-foot homes, slim inside at 15-feet wide, are rising. “I think the change is bothersome.”

That fact was made crystal clear, she said, when at a neighborhood meeting, one community leader accused the Rotherses and their project of being “racist.”

“I think the feeling is, ‘My family won’t be able to afford to live here anymore. It’s not our neighborhood anymore.’ I mean, look at this,” Anne said of some of the houses going up. “This is a big, big change.”

Greg, like others, pointed out, “We didn’t tear anything down. It was vacant land that we’re coming in and improving. I mean, we’re not coming in and tearing down homes that were family-owned or anything.”

“It’s an opportunity that exists,” Anne said. “I mean it (the land) had been sitting here for a long time. My feeling is that everybody who wanted to do something different with it had the opportunity. We had the vision and we thought it would be popular, and it has been. … We do our best to be respectful.”

Grant Baumgartner, 44, a founding co-partner in the Edward Franklin Building Co., said it was blowback at a neighborhood meeting that prompted his company to scale back a project they had planned at 21st Street and Belleview Avenue.

“There were like 20, 25 people there. And they were angry, oh my God,” Baumgartner said. The plan was to erect five, three-story townhomes on a subdivided lot. “They were complaining that the houses are too close. No one had spoken to them. They felt like we tried to circumvent them to just do this thing and get in as many houses as possible.”

Baumgartner said he worked to convince residents that they never intended to insult or circumvent anyone.

“We apologized,” he said, and began working with neighborhood groups.

Instead of five side-by-side homes, they built four.

Diane Kuenne, 55, and her husband, Jeff, 59, moved into theirs 14 months ago. Its rooftop view overlooks the city. They were drawn to the house in part because it blended into the block and did not “shock the neighborhood.”

“We wanted to integrate into the neighborhood instead of being the problem that caused people to move,” said Jeff, his last name pronounced “Kenny.”

“The neighborhood is endearing and embracing if they sense that you’re here to be part of it, and not walk all over it.”

Something better

Where an old tavern once stood, a near quarter-acre garden occupies half the block at 17th and Summit streets. Kathy Marchant sat in its greenhouse as rain pelted the roof.

For 40 years, Marchant has witnessed the West Side’s gentrification, benefiting in ways she never anticipated

In the 1990s, it was Marchant and her partner turned husband, Michael Martin, who bought the lots that created the garden, hauling manure up from the stockyards. Before that, they were the ones who bought the crumbling red brick building across the street to start the Blue Bird Bistro, never guessing that their little “Mayberry” place (the bistro later sold to owner Jane Zieha) would one day anchor businesses surrounded by $1 million homes.

That’s because in 1982, the year the couple and their then-8-year-old daughter moved into their house on Madison Avenue, the neighborhood was almost nothing like it is today. When Marchant views the West Side’s changes, it’s through that lens.

“It was really high poverty,” Marchant recalled.

The cost of their house, built in 1881, was $12,000. The couple, artists out of the Kansas City Art Institute, owned so little, no bank would give them a loan.

“We couldn’t afford it. So the person who owned it financed it for us,” Marchant said. Skilled at carpentry, she would fix it up. Others were doing likewise.

“The reason I moved here,” she said, “is because I had friends who lived here who were artists. Artists were moving in. … I would say, in the early ’90s, on our one block, I counted 29 art school graduates.”

What others remember: drugs, murders, gangs, robberies.

Gus Juaurez of Los Alamos Cocina lived on the north West Side then.

“Bad, bad,”said Jaurez who said gentrification has been only positive for his business. “I’m going to tell you exactly what it was back then. You heard shotguns, somebody killed. We were afraid to come to the Boulevard.”

So Zita Ramirez attests. Age 66, a Children’s Mercy Hospital nurse retired after 41 years, she was a young mom in 1984 when she built her home — just over 1,000 square feet — on the hillside near 18th and Jefferson streets. She was lured by a Westside Housing Organization program offering down payments, plus 15 years of no property taxes to get people to move in.

“It was blighted. It was very, very bad,” Ramirez said. She recalled empty lots strewn with garbage, refrigerators, couches. She feared letting her two children play outside.

“It was very dangerous. There was always shootings. I never walked at night. I think people don’t remember it,” she said.

Many Hispanic residents by then had already left the West Side, Ramirez said, including her parents, who had grown up in the Sacred Heart and Guadalupe neighborhoods.

“They moved out because they wanted something better,” she said.

Opinions differ on when the West Side began to improve. Nearly all agree 1998 was a turning point. That’s when the former crime-ridden Pennway Plaza housing project was replaced by 120 picturesque Villa del Sol townhouses. A development created by McCormack Baron Salazar and HUD, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, it offers apartments from low-income to market rates. (Two-bedroom townhouses rent even now for $775 to about $1,200, depending on income).

The FBI headquarters at 12th and Summit opened that same year. Downtown was coming back to life. The Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts broke ground in 2006. The Sprint Center, now the T-Mobile Center, opened in October 2007, with the Power & Light District a month later.

“It’s been a 30-year process,” Marchant said. “And it had to happen. Half the buildings on our block no one had lived in for years. Without people moving here, saving the houses, this neighborhood would not be here. …

“There are people who are my generation who are really upset (about the $1 million homes), that it’s not what they wanted to live in. The trouble is we made it a beautiful, sparkling place. People want to be in a beautiful, sparkling place. It’s just human nature.”

Ramirez is not complaining. Gentrification may have raised her taxes, but it’s also raised the value of her property as an asset. It’s a reason people have sold. And, she believes, it’s saved what was a languishing neighborhood.

“I love it,” she said of the new homes. “I think it’s artistic. I like the mixed neighborhood. When you go to any big city, that’s what you see. I think that’s OK. I’m a firm believer that you should be able to do what you want with the property you have.”

Next door to Ramirez lives physician Patrick McCormick and his partner, Barry Eisenhart, an artist and trainer. Their home, finished in 2007, with its 24-foot-tall wall of windows and curved roof (Zillow prices the 4,800-square-foot home at $2 million) is among the largest and most visible from Interstate 35. Its 25-yard lap pool, hot tub and garden patio overlook downtown.

“When they proposed building the Kauffman — the rendering of the Moshe Safdie building was in the paper — I said this is going to have the best view of the Kauffman Center,” McCormick said.

And pretty much of everything else. On the Fourth of July, they can see fireworks as far off as Overland Park.

McCormick designed the house himself, buying multiple lots in 2000 when the parcels were empty and the only other homes on the crest of the hill were an underground house and, to the north, a 1983 inverted “L”-shaped house that the owners, the Wilson Development Group, tore down in 2007.

“We get accused of tearing that down,” Eisenhart said. “We had nothing to do with it.”

When McCormick looks to the West Side’s future, he too pictures ever-more development.

“It will probably be filled in with a lot of contemporary homes,” he said, which he hopes doesn’t come at a steep price. “I would hate this neighborhood to lose its Hispanic element. It’s one of the things I love.”

‘353 Tax’

An ordinance passed in September may offer an answer — at least for a while. The official name is a mouthful: The Westside Owner-Occupant Residential Property Chapter 353 Development Plan.

Most just call it “353 Tax.”

“The main point is to preserve the West Side as the cultural hub and heart of the Mexican community,” said resident Colleen Hernandez, former CEO of the Kansas City Neighborhood Alliance. “They’ve created this sense of community. They’ve lived here all their lives. They’ve raised their kids here and want to die here.”

The plan’s main goal is keep people in their homes, keep them from being run out by high property taxes. The City Council’s 10-2 vote to approve the ordinance allowed the entire West Side to be declared “blighted.” As a result, Chapter 353 of Missouri’s tax code allowed residents who were homeowners as of Sept. 29 — when the ordinance was passed — to sign up for as much as 25 years of tax abatement that does more than freeze their property tax rate, it lowers it.

Depending on household income, homeowners can receive property tax breaks ranging from 10% (for the highest earners) to 40% to perhaps paying no more than 2.65% of their household income, or even only taxes on their land. Moreover, part of the money that higher income residents pay goes to administer the program as well as provide services to their lower-income neighbors.

The plan is being administered through the Westside Housing Organization with Legal Aid of Western Missouri.

“We’re not fighting gentrification. We’re not fighting rich people. We’re not fighting white people. We’re fighting to retain the Hispanic nature of the community,” Hernandez said.

Stakeholders in the community insist they will do the same.

Lopez of the Guadalupe Centers acknowledges that many of the Hispanic people they serve now live in the Northeast area of Kansas City, so they have expanded their programs there. The Guadalupe Centers’ grade school and high school are now on the East Side. But the middle school is still on on the West Side. After-school programs, like spring baseball, are there, too. The organization has run an adult day care for 20 years.

“Seniors are here every day,” Lopez said.

Raised in West Side public housing, John Fierro, 57, moved back to the neighborhood 19 years ago. As a boy, he played baseball at the Guadalupe Centers and worked there as a teen. He did ceramics at the Mattie Rhodes Center, a nearly 130-year-old community organization where he is now executive director.

Fierro suspects the West Side will continue to slowly change.

“I think it’s going to be culturally diverse,” he said, predicting a West Side that drops to 40% Hispanic, maybe 35%, in a decade.

Whatever the case, neither he nor Mattie Rhodes is going anywhere.

“The pride and dedication to preserve one’s culture and one’s history is the same,” Fierro said. “You know, my wife and I have already talked. One day we’re going to leave the house to one of our kids, with the understanding, ‘Well, you’re going to come live here. You’re not going to sell it.’

“So that is our kind of contribution to the future that, ‘Hey, we want to preserve Hispanic culture here.’ … This community raised us. We owe this community.”

Includes reporting by The Star’s Kevin Hardy.