The little sub that could: Woods Hole tests the limits of science with 'Alvin' submersible

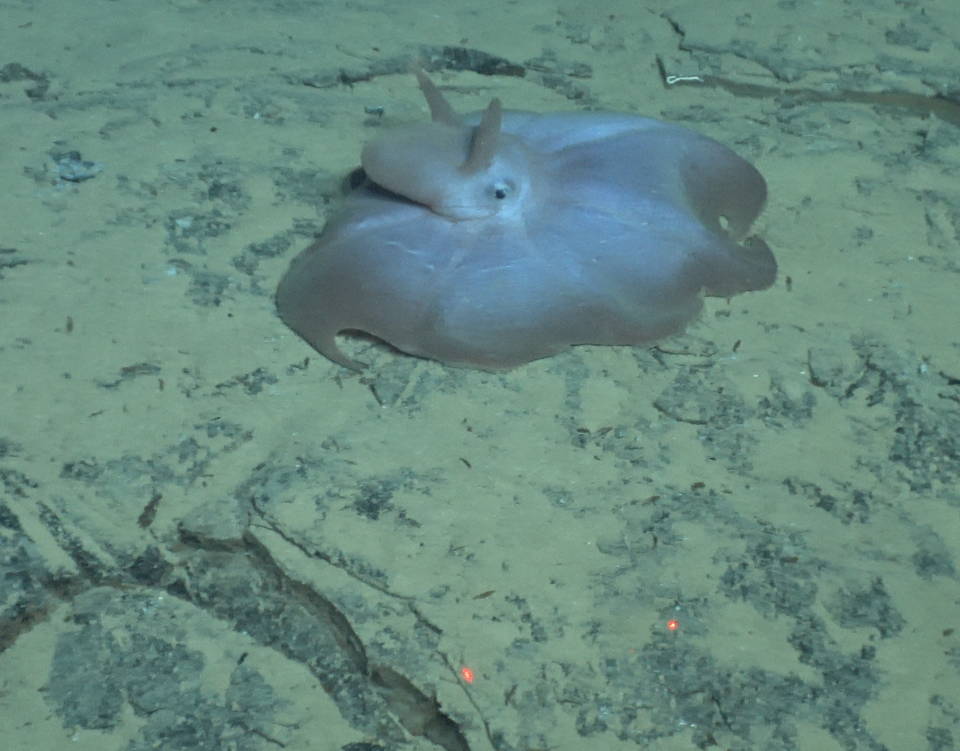

For a moment, the animal looks like nothing more than a bluish, amoeba-like blur on the seabed. Then, sort of like an inflated latex glove. But as the scientists maneuver closer, it takes shape: First stubby arms, an inky black eye, a bulbous head with endearing, ear-like fins.

A Dumbo octopus — a rare, deep sea umbrella octopus known to scientists as "grimpoteuthis," often called "the world's cutest octopus" because of its usually small size, plump shape and floppy "ear" fins that bring to mind Disney's flying elephant baby, Dumbo.

"That is amazing," one of the scientists can be heard saying as the octopus comes into focus.

"Oh my gosh, that's so cool," a second comments.

"He's very deep."

Capturing a Dumbo octopus on video

There is brief discussion about the difficulty of getting the zoomed-in camera to center on the animal, resting on a seafloor puckered with ancient pillow lava at the Mid-Cayman rise — a divergent plate boundary at one of the deepest points on the floor of the Caribbean Sea, near the Cayman Islands.

"Let's go nice and slow with this. Nice and slow," the first scientist says, his voice measured and calm. "Ok...line it up for the shot."

On the seabed, the pale octopus begins to flush, its pale flesh darkening to purplish and dark gray tones, its arms beginning to tense and curl, the skin between its tentacles starting to undulate like the folds of a Mexican Jalisco dancer's skirts in slow motion, giving glimpses of the first row of ruffle-like suckers underneath. The round, dark eye seems to reflect some wariness, but the animal does not flee — it has no predators here, but it is unaccustomed to the light flowing over its body and to the hum of machinery muffled by the weight of the sea stretching out overhead, no doubt its first human-created sound.

"I'm getting some awesome video right now," the second scientist announces, his voice low but barely containing the excitement.

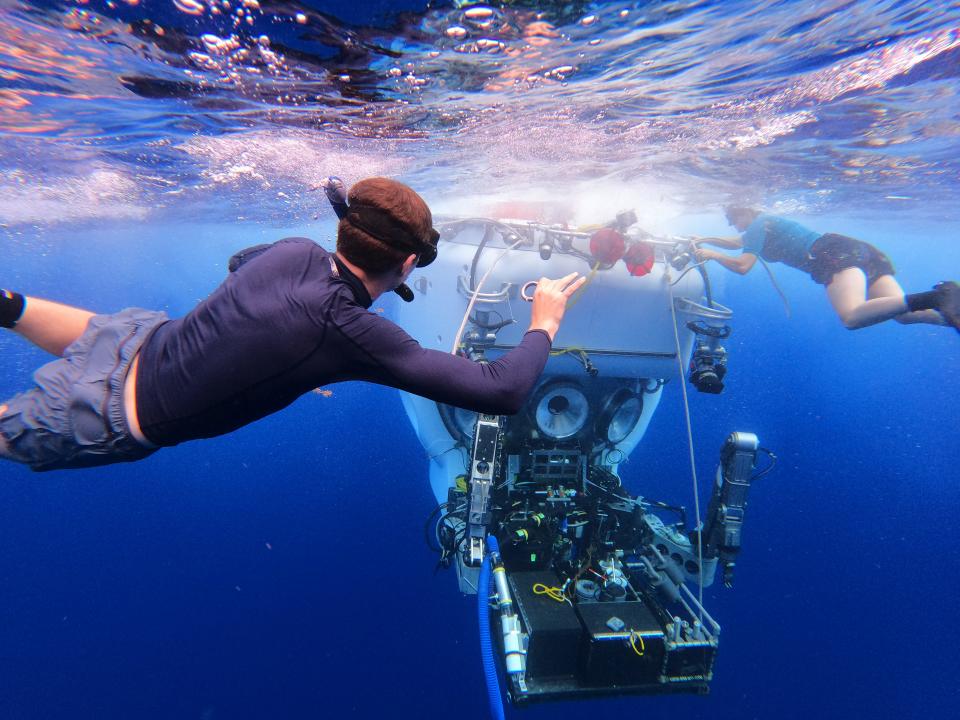

This was just one of the conversations that took place only a few weeks ago as scientists from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, joined by fellow scientists from other institutions, ran the research facility's recently upgraded, human-occupied submersible, Alvin, through the proverbial gauntlet at the Mid-Cayman Rise and the Puerto Rico Trench.

WHOI Associate Scientist Anna Michel, chief scientist of the National Deep Submergence Facility that operates the U.S. Navy-owned Alvin, explained that the science verification expedition — which consisted of 14 dives at and near the boundary of the Caribbean and the Atlantic over the course of three weeks this summer — was to test Alvin's scientific and engineering systems to make sure the submersible can be used for deep-sea sample and data collection.

Pushing the depths of science in earth's final frontier

Just prior to the science verification cruise, Alvin underwent sea trials starting in early July to achieve a new depth rating of 6,500 meters — or, to put it in more relatable terms, an astounding four miles.

For the research facility scientists, that's something to be excited about, especially considering that the very deepest point on the planet is about 6.8 miles, at the Mariana Trench's Challenger Deep.

From the depths: UMass Dartmouth gets funding to build new Biodegradable Plastics Lab

Once the depth rating was achieved, "we went out as scientists, and we brought a lot of early career scientists and new users to the program, to kind of test the scientific capabilities of the sub at these new depths," Michel said.

There is a lot of scientific equipment, including a new imaging system, that needed testing, she said.

"Science hadn't been using the sub at these new depths so we were really putting the sub through the paces to show that we could do science at these new depths," Michel said.

The effort was a resounding success, and the research institution is now sharing the results and some of the images.

“We set a high bar for Alvin, and it easily met or exceeded our expectations,” said Michel.

She and University of Rhode Island geophysicist Adam Soule led the science verification mission, conducted from the research vessel Atlantis, and both participated in the dives.

At the Puerto Rico Trench, five dives were completed. Those dives focused on Alvin's "ability to support multi-disciplinary research, including geological sampling and observation, among the towering cliffs formed by the collision between the North American and Caribbean tectonic plates, and biological sampling at abyssal and hadal depths," according to the research facility.

There, the scientists made direct observations of some of the deepest seabed areas in the Atlantic Ocean. They also collected samples of 100 million-year-old oceanic crust, as well as biological organisms — among them the deepest known specimens of their species.

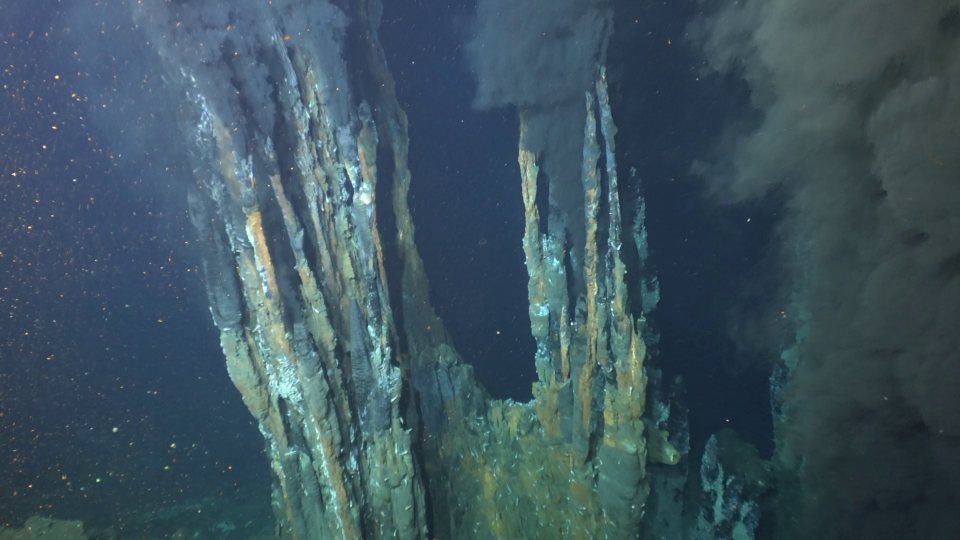

Then they proceeded to the Mid-Cayman Rise, described as the point "where the two plates are separating at a rate of about 15 millimeters (0.5 inch) per year." Nine dives were conducted there, focusing on "chemical and biological sampling around hydrothermal vent and seep sites, including at the Beebe Vent Field — the hottest and deepest known hydrothermal vents on Earth," the scientists said.

The Dumbo octopus was a highlight near the end of the mission, coming into focus during a mid August dive.

“These were complicated dives in complex locations that posed a test not just of the sub, but of the people who operate it and who make the science possible, as well,” said Soule, who was the chief scientist of the research institution's National Deep Submergence Facility before taking a professorship at the Rhode Island university and leaving Michel in charge.

Achieving a long-time goal

For Soule, the summer's accomplishments — the new depth certification and the successful testing of scientific equipment — were the realization of a long-time goal. Before a seven-year stint as the chief scientist of the submergence facility, he spent 17 years as a WHOI scientist. For a decade, he said, he was involved with pursuing upgrades to Alvin. A first set of improvements were completed in 2014, followed by the most recent overhaul that started in March of 2020, funded by the National Science Foundation.

"It just is really gratifying to see this vehicle reach this stage. This has been a goal for the Alvin group and the scientific community for many years — to enhance its depth rating and capability to look deeper into the ocean," he said.

Alvin's latest upgrades include new titanium ballast spheres, an upgraded hydraulic system, new thrusters and motor controllers, updated command-and-control and navigation systems, and a new 4K imaging system.

Soule, who has undertaken about 25 dives in Alvin, said the new depth certification is a remarkable milestone for the submersible, which was commissioned in 1964 and was the first deep-ocean submersible. Its previous maximum depth was 4,500 meters — about 2.8 miles.

"When it could dive to 4,500 meters, that allowed it to do science in maybe 70% of the ocean," Soule said. "What's exciting with this new depth certification is, it makes 99% of the ocean accessible to this submarine. Its ability to dive to these depths and bring back samples makes it a special tool."

A deeper dive: 'The ocean is alive': After $50M upgrade, research sub Alvin can reach 99% of ocean floor

Michel is just as effusive about Alvin's capabilities, and its future.

"Alvin is used by scientists all across our country to do scientific research," she said, calling it "a national asset." She explained that scientists can write grants for a chance to use Alvin, and the sailing vessel that carries it, for their research.

Working with Alvin is "really exciting," said Michel, who completed her first dives in Alvin this summer.

"It was incredible," she said, still sounding awed by the experience.

Going into the depths can be like looking into the night sky

During dives, Michel said, time seems to cease existing. It can take two- to two-and-a-half hours to reach the seafloor during the deepest dives, but it feels like no time at all.

"Initially the light still gets through the water, so you can see the water is a really, really blue color, but soon you lose the light in the water so everything is pitch black," she said. "If you turn the lights on and off on the sub you can see all the bioluminescence, which kind of reminds me of looking into the night sky and you see lots of stars. It kind of reminds me of that. You kind of see all these little critters lighting up."

Soule also talks about how the perception of time seems to be warped in the depths.

"You're down there for eight hours, but it goes by in a flash," he said.

He finds the transition between light and dark fascinating, as well.

"When you first get into the ocean there's this really vibrant blue out of the viewports, and as you descend the blue gets deeper and deeper, going to dark blue, to indigo into navy to black," Soule said.

Going from the part of the ocean lit up by the sun to the part that is dark, he said, "is a signal that I'm going to a place that is pretty alien, that no human has ever seen before, and that has the potential to reveal new discoveries. That's the part I like."

Even though this summer's dives were primarily for testing equipment at depth, he noted that there were still discoveries taking place, "like expanding the known range for different organisms."

Michel said she found the Mid-Caymen Rise and its Beebe Vent Field quite awe-inspiring, with its hydro thermic vents and colonies of extremophiles — shrimp and tube worms that have adapted to thrive at extreme depth and extreme heat.

"I've done quite a few cruises to vent sites before (with remotely operated vehicles). But the Beebe Vent Field...it was just the most incredible sight I've ever seen," she said, describing it as "Dr. Seuss-like."

Putting a stamp on history: Postmark honors WHOI

She found it interesting not only because of the surreal and strange beauty of it all, but also because her group at WHOI works on developing new instruments to study ocean chemistry — tools used to understand the geological processes through the fluids flowing through the seafloor vents.

"It is very exciting. I feel very lucky to get to work in the deep ocean," Michel said.

'It changes... your understanding of your place on the planet'

Soule, the Alvin veteran, said he found it especially exciting to watch a new generation of scientists experience the vehicle, and see the deep ocean floor, for the first time.

"Seeing them have their first experience of kind of seeing the sea floor is just awesome," he said. "For people who've studied the deep parts of the ocean for many years to then see it with your own eyes for the first time...it changes the perception of your work, and your understanding of your place on the planet."

He said he hopes these scientists will "become the next generation of scientists who use the sub to make discoveries and change the way we think about the ocean and the planet."

"The way it works is, you're trying to push the limits of knowledge," he said, "and a tool like Alvin is great at helping you do that."

Now that the submersible has been put through the paces for deeper exploration, and passed the tests with flying colors, Michel said, “Alvin is ready for science.”

Its first scientific expedition with its new depth certification sets sail into the northeastern part of the Gulf of Mexico on Sept. 24, to study methane seep sites, she said. And when that mission is done, there are several other cruises already lined up.

It is possible Alvin could be away, exploring the great blue depths, for the next five years, Michel said.

So, perhaps its mission log could begin this way: "The ocean: The final frontier on earth. These are the voyages of the human-occupied submersible Alvin. Its five-year mission: To explore strange new seabeds. To seek out unknown life and geological processes. To boldly go where no one has gone before!"

Federal workforce training: Will the program help invigorate Cape Cod's graying fishery industry?

This article originally appeared on Cape Cod Times: WHOI scientists go to new depths with 'Alvin' submersible