The story of Raleigh’s Red Hat began with a fight against Microsoft

“How is that possible, that one of the world’s biggest technology companies ... loses the product of the year to a company with 50 employees in the tobacco fields of North Carolina?”

Heading into 1998, the software provider Red Hat was little known outside a core of coders and computer geeks.

The 5-year-old company worked out of nondescript offices in Durham where it employed fewer than 40 people. Local press was rare, let alone national attention. Its unique approach to software, called open source, was niche, arcane and not obviously profitable. How do you build a business off a free code?

Its location didn’t help, either.

Nearly 40 years after North Carolina leaders established Research Triangle Park, the region still wasn’t known for producing major tech firms. By the late 1990s, the only homegrown star startup was the Cary analytics firm SAS Institute. A 1998 article in The Wall Street Journal listed the Research Triangle among the nation’s “second-tier technology outposts” while a Newsweek cover story from that time excluded Raleigh and Durham from its rankings of hot tech cities, instead naming Seattle, Austin and even Boise, Idaho.

The reputation of the Triangle would soon grow. Red Hat’s would, too — even faster.

By the end of 1998, the company had blasted onto the national stage as a major disrupting force in software, attracting media, investors and ardent fans worldwide.

Within two years, Red Hat would be the most valuable public company in the Triangle.

“It was kind of surreal the amount of fame you’d get for working at Red Hat,” said Joe Colopy, who started as an intern at the company in the spring of 1999. “It was just that cool.”

A quarter-century since it broke out, and despite recent news about what may be the company’s first-ever layoffs, Red Hat continues to define the area in myriad ways: delivering prestige, dollars, spinoff startups and downtown revitalization — plus an amphitheater.

It’s gone from a few dozen employees to thousands, from $10 million in yearly revenue to being bought by IBM for $34 billion. Every product launch or layoff round is closely tracked. Its founding ethos — an insurgent spirit promoting a then-revolutionary, now-commonplace concept of free information — lingers today.

Will Red Hat’s identity endure as it operates within its larger multinational parent? Will Raleigh or Durham lose what makes each city distinct as new corporations move in?

Other tech companies may hire more people in the region, but Red Hat is truly the Triangle’s own.

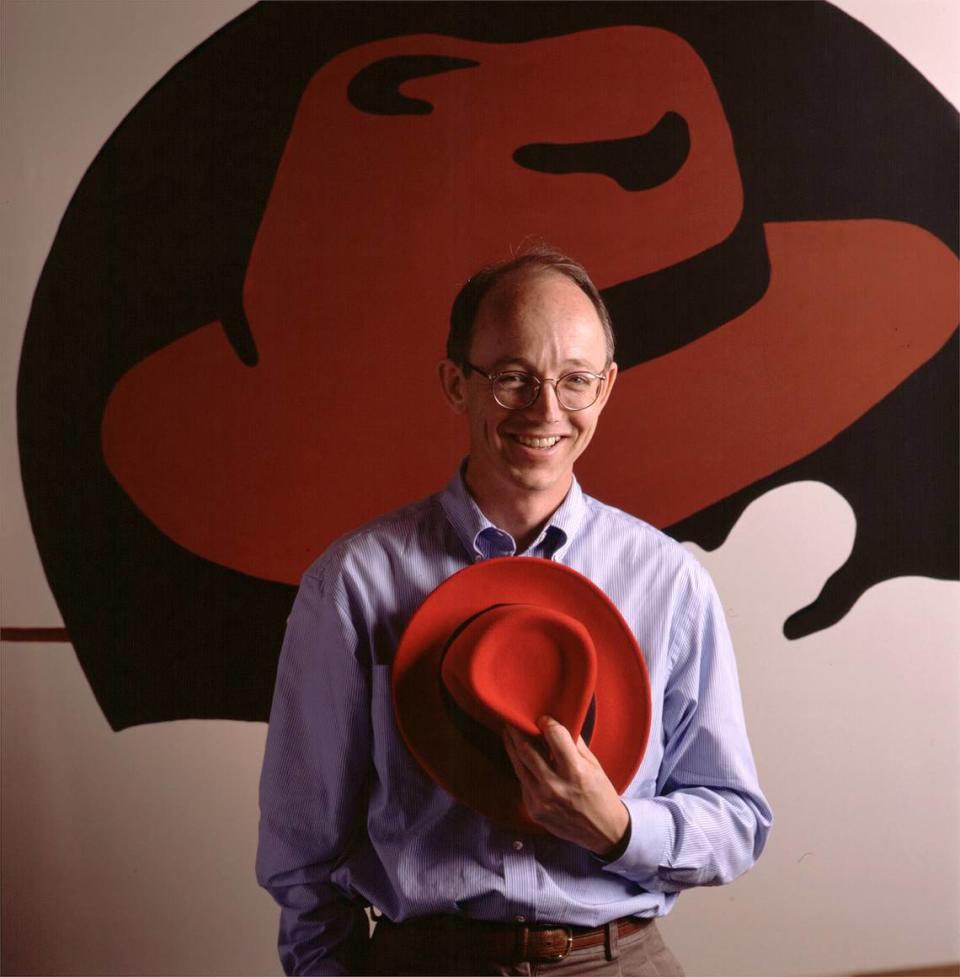

Bob Young, one of Red Hat’s two founders, pinpoints his company’s breakthrough to February 1998, when the tech magazine InfoWorld awarded its Operating System of the Year honor to Red Hat’s Linux 5.2. At the time, Microsoft controlled more than 85% of the market for operating systems, yet its omnipresent Windows 98 was bested by a little-known competitor from “a second-tier technology outpost.”

“How is that possible,” Young said, “that one of the world’s biggest technology companies, on this strategically critical product, loses the product of the year to a company with 50 employees in the tobacco fields of North Carolina?”

The answer, he would tell the many reporters who suddenly wanted to learn about his upstart company, strikes at “the beauty” of open-source software.

“Our engineering team is an order of magnitude bigger than Microsoft’s engineering team on Windows, and I don’t really care how many people they have,” Young would say. “Like they may have thousands of the smartest operating system engineers that they could scour the planet for, and we had 10,000 engineers by comparison.”

It started with a student from Finland

In 1991, a Finnish student named Linus Torvalds created a PC operating system called Linux. Rather than market his system, Torvalds famously posted its source code — its blueprint — online, allowing anyone to use Linux for free and suggest improvements.

A key advantage of Linux, Young explained, is that anyone can see its manual. Anyone, he argued, can make it better. If Linux were a car and there was an issue under the hood, its owner wouldn’t be reliant on the automaker to fix it using guarded instructions. This is the model Red Hat built its company around.

“We gave the customer control over the technology that customer was using,” Young said. “So we were not selling software, we were selling service. We gave away the software.”

Torvalds didn’t invent open source, but his decision to free Linux captured the imagination of programmers worldwide like Marc Ewing, a recent college graduate who moved to Durham for a two-month job at IBM. Finding his IBM work boring, Ewing began tinkering with Linux in his spare time, adding additional open-source platforms to the Linux kernel, or core, to create a program that enabled people to run computer tasks. He sold a few hundred of these bespoke Linux versions and named the product Red Hat after his grandfather’s Cornell University lacrosse cap.

Young was a 40-year-old Canadian computer equipment salesperson with a software catalog when he noticed what Ewing was doing. It’s pretty primitive, but it’s going in the right direction, Young thought. He began reselling Ewing’s Red Hat product.

Eventually, he called Ewing, and the two met at a tech conference in New York City.

“I needed a product, and Marc needed some marketing help,” said Young, who was living in Connecticut at the time. “So we put our two little businesses together.”

Red Hat takes on the Microsoft Goliath

Red Hat incorporated in March 1993, with the earliest employees operating the nascent business out of Ewing’s Durham apartment. Eventually, the landlord discovered what they were doing and kicked them out.

For the next few years, the company released new versions of its Linux operating systems on CDs, marketing them to computer science students and technical researchers. Red Hat made occasional headlines, like when a visual effects group used its Linux 4.1 to design parts of the 1997 film “Titanic.”

Then, over the course of 1998, Red Hat emerged, playing the perfect foil to Bill Gates’ Microsoft at a moment when anti-Microsoft sentiments were running high.

In the late 1990s, the Seattle-based tech behemoth was entangled in a federal antitrust lawsuit over its dominant Windows operating system. Red Hat, conversely, was a more ragtag operation that seemed to relish in poking Goliath. It was hip where Microsoft was establishment. Its business was predicated on a free and open source software, while Microsoft charged around $90 for its operating system. Microsoft was owned by the richest person in the world. Red Hat engineers were still linking servers together with extension cords.

“The only way you can compete against a monopoly is to change the rules on which the game is played,” Young said at the time. “It allows me to sleep at night knowing we compete under different rules.”

Halfway through 1998, Red Hat was on pace to ship 400,000 Linux CD-ROMS. It then picked up two corporate investors, as Intel and Netscape announced they would create products that could run on Red Hat’s Linux. The following year, Red Hat struck similar partnerships with Hewitt-Packard, Compaq, Dell and IBM to offer customers Linux on their servers.

It grew its office footprint, too, opening offices in the United Kingdom and Germany.

In 1999, Red Hat moved its headquarters to Durham’s Meridian Business Campus, which offered six times more space. There, on the wall, the company painted a Ralph Waldo Emerson quote: “Every revolution was first a thought in one man’s mind; and when the same thought occurs to another man, it is the key to that era.”

Talk of Red Hat going public intensified. In the spring, Red Hat kicked off a 12-city promotional trip it labeled Red Hat Revolution Tour 1999. Each stop drew cheering crowds who arrived in company T-shirts. Almost 200 people attended one tour event in Midtown Manhattan.

On Aug. 11, 1999, Red Hat hit the stock market with the eighth-largest first-day gain in Wall Street history, its share price leaping from $14 to $52,

Red Hat ended its first day as a public company worth $3.5 billion, making overnight millionaires of its earliest employees. After its second day of trading, the company was valued at $4.85 billion. $5.7 billion by the end of third day. The next month, its valuation surpassed $7.2 billion, making Red Hat the Triangle’s most valuable public company.

The scrappy open-source underdog had officially arrived. Or, as The News & Observer columnist Jim Jenkins put it in August 1999, “The once-meek have already inherited.”