Live to tell: A few who survived the Holocaust remember so that others do not forget

On Jan. 27, 1945, Red Army soldiers found 7,000 barely living souls still inside the Auschwitz concentration camp and set about trying to help them even as they tried to absorb the enormity of the crime they represented.

There is no moment of liberation but the date is set aside now annually for the rest of us to, yet again, absorb the enormity of the crime.

On our pages today are a few of the faces of Holocaust survivors still living in and around Cincinnati. Still living. Testament to human endurance and will.

Commentary: A rabbi reflects on the Holocaust and how, in some ways, we have not learned much

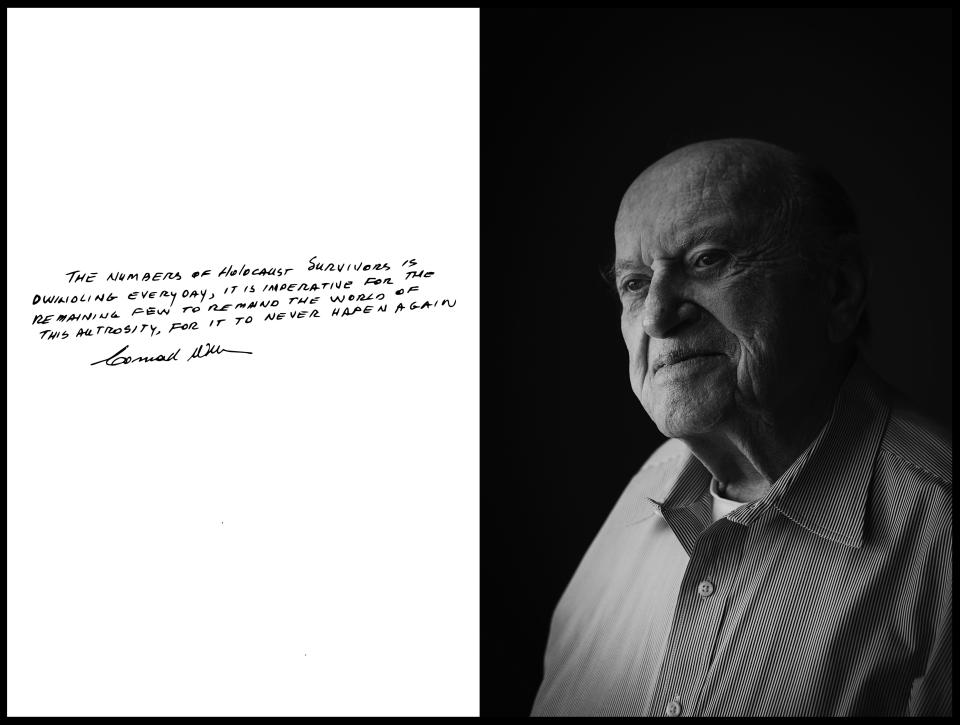

Conrad Weiner: "The number of Holocaust survivors is dwindling every day, it is imperative for the remaining few to remind the world of this atrocity, for it to never happen again.”

Conrad Weiner was born in Storojinetz, Romania in 1938. In 1941, Conrad was taken by cattle car for two days and one night and then forced to walk for two weeks in the snow to Budi, a forced labor camp. Conrad was only three and a half years old. When he arrived, he grew very sick and many of the other prisoners told his mother it was too late to help him. But she didn’t give up. She nursed him back to health, and in 1944, Conrad and the other 300 surviving prisoners were freed by the Red Army and sent back to Romania. In 1960, Conrad and his family immigrated to the U.S. Conrad was drafted into the U.S. Army shortly after he arrived, but he eventually moved to Cincinnati in 1963, where he lives today.

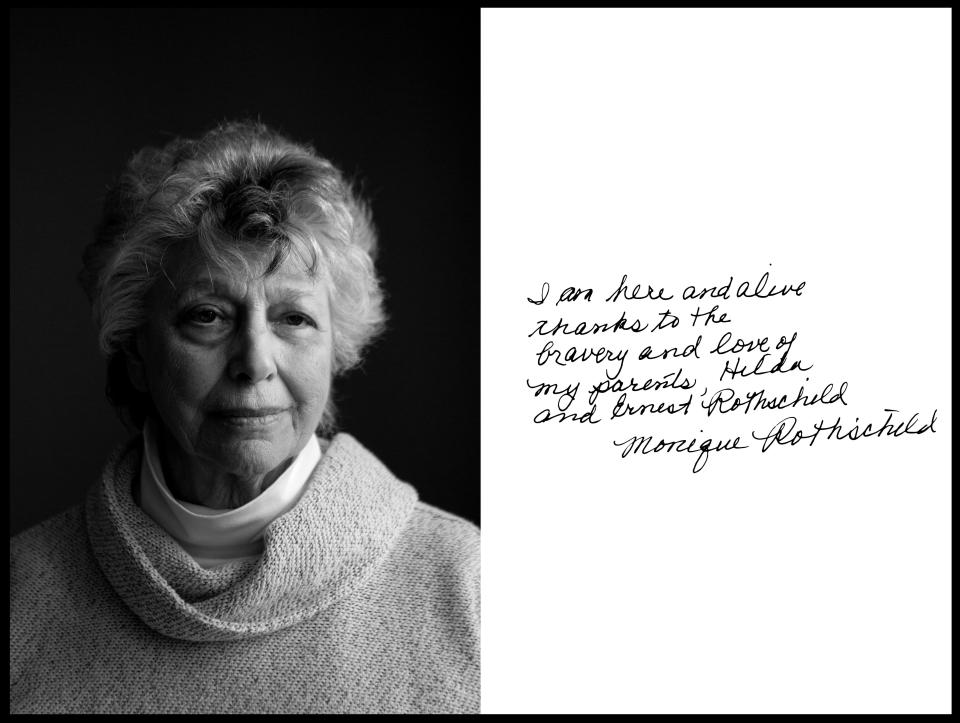

Monique Rothschild: “I am here and alive thanks to the bravery and love of my parents, Hilda and Ernest Rothschild.”

Monique Rothschild was born in Bellac, France in November 1940. Her parents, Ernest and Hilda fled Nazi persecution when she was born. First, they traveled across France to Spain, where they later boarded the Navemar ship in August 1941. They arrived at Ellis Island about a month later. They had family in both Cincinnati and New York, so they moved to Cincinnati, where Monique lives today.

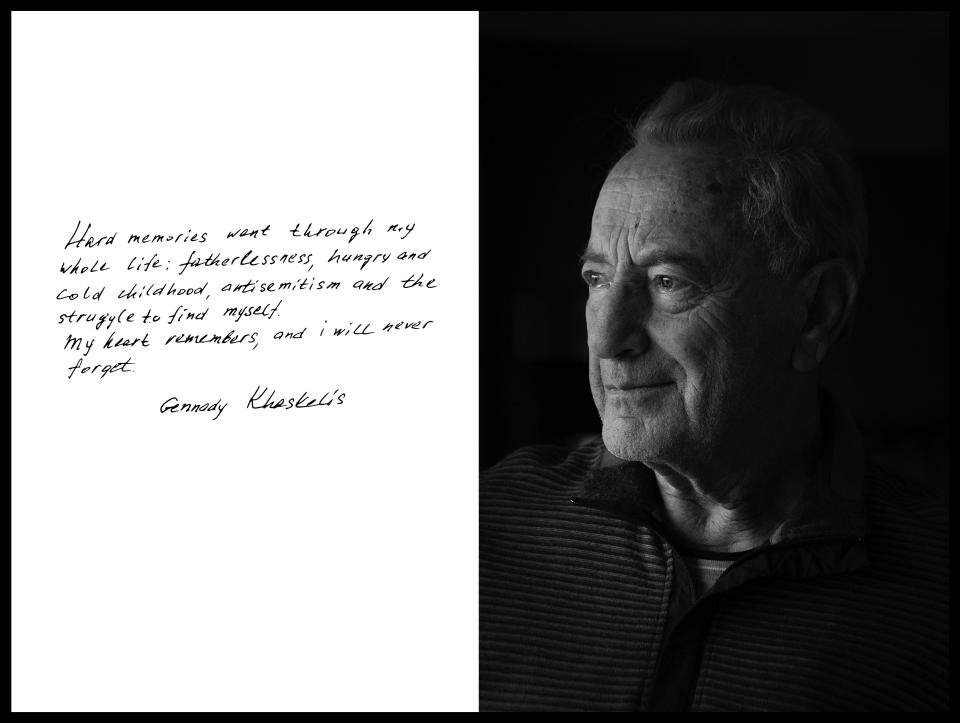

Gennady Khaskelis: “Hard memories went through my whole life: fatherlessness, hungry and cold childhood, antisemitism and the struggle to find myself. My heart remembers, and I will never forget.”

Gennady Khaskelis was born in Kiev, Ukraine, in June 1940. He fled to Uzbekistan with his family shortly after the war began, but his father stayed in Ukraine to fight against the Nazis. His family later returned to Kiev in 1945, but they didn’t have much food and for many years, they had to live in a small, crowded space to survive. In 1994, a network of Jewish organizations brought Gennady, his wife Inna, and their two young children from Kiev to Cincinnati. Inna and Gennady were both engineers in Kiev, but when they arrived in the U.S., they didn’t speak English and couldn’t drive. “It was very difficult,” they said. Jewish Family Service taught them English and helped them find jobs. Their son went on to get a Ph.D. in chemistry at UC and their daughter went to Harvard and Columbia Law School. Today, Genaddy and Inna still live in Cincinnati.

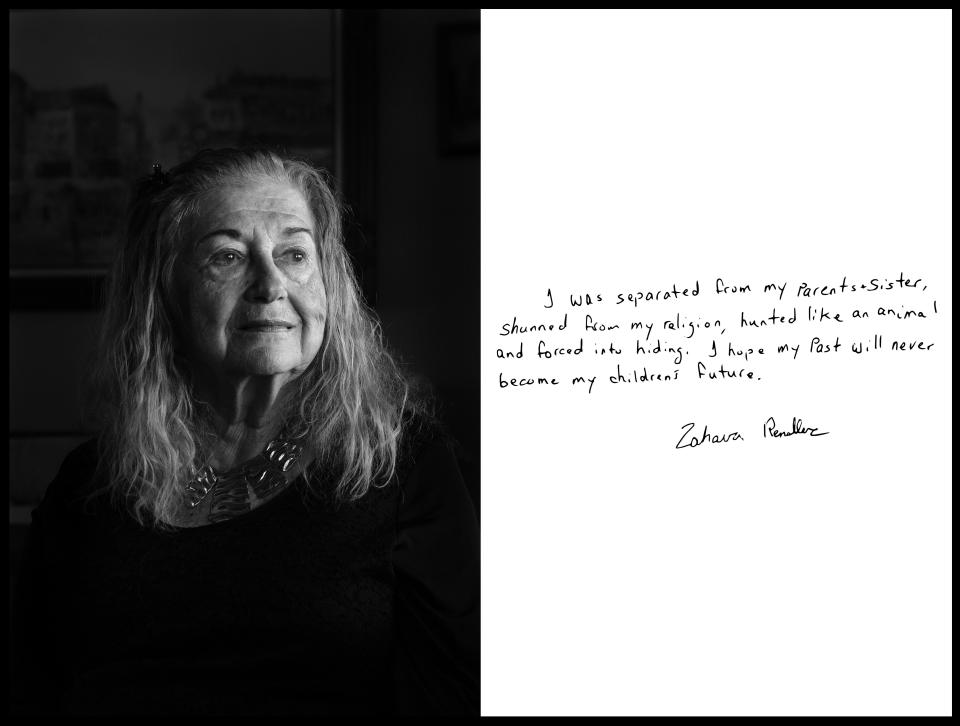

Zahava Rendler: “I was separated from my parents and sister, shamed from my religion, hunted like an animal and forced into hiding. I hope my past will never become my children’s future.”

Zahava Rendler was born Golda Feuerberg in March 1941, in Stryi, Poland. Zahava was born near the start of the war and immediately went into hiding in an underground bunker with her family and 25 other people. She was given sleeping pills to keep her from crying. Later, she was given false papers with the name Olga Pachulchak, and her parents sent her to live with a woman in Poland for a year. The woman later thought it was too dangerous, so she sent Zahava to a convent. After the war, her father found her in the convent, but the nuns wanted her to stay. Her father helped her sneak out and she was reunited with her family. In 1946, her family worked for a group that helped survivors illegally go to Palestine. The British caught them and sent to a displaced persons camp in Cyprus. Later, Zahava’s family was permitted to move to Haifa, Israel, where she changed her name from Golda to Zahava, the Hebrew word for gold. She moved to Cincinnati in 1963.

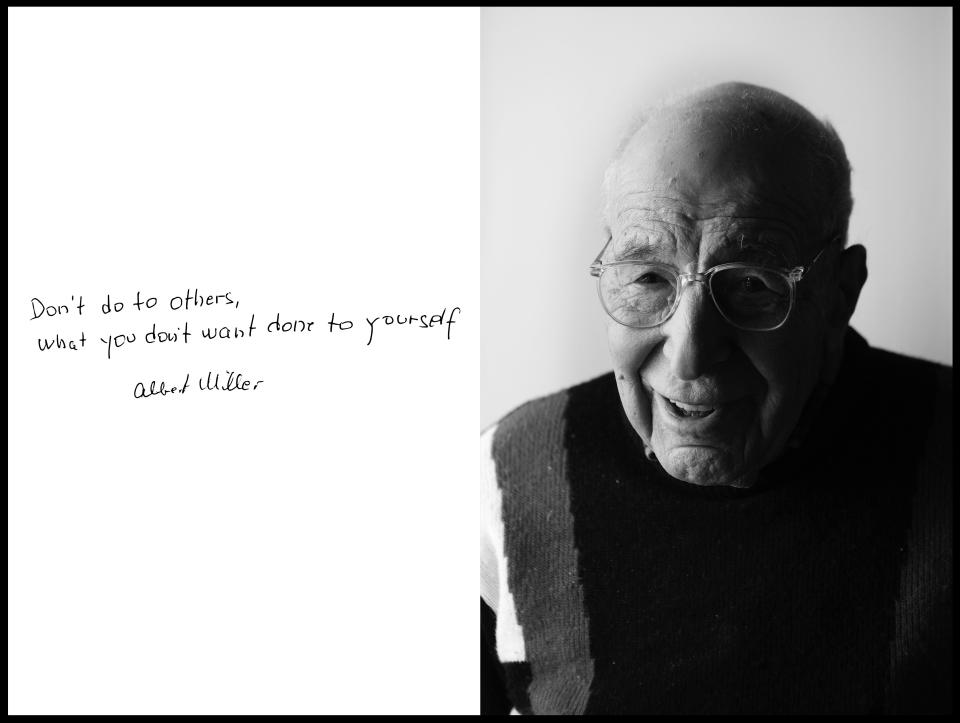

Albert Miller: “Don’t do to others, what you don’t want done to yourself.”

Albert Miller was born in 1922, in Berlin, Germany. In 1937, he left Nazi Germany to go to Switzerland. He later traveled to Belgium, the Netherlands, and then London, England, where he met his older brother Bruce. Albert’s parents stayed in Germany, surviving Kristallnacht by hiding in a friend’s house. They escaped Germany with the help of a friend and a consulate, who replaced their travel documents stolen by the Nazis. Albert was reunited with his family in England before he moved to the U.S. in 1939.

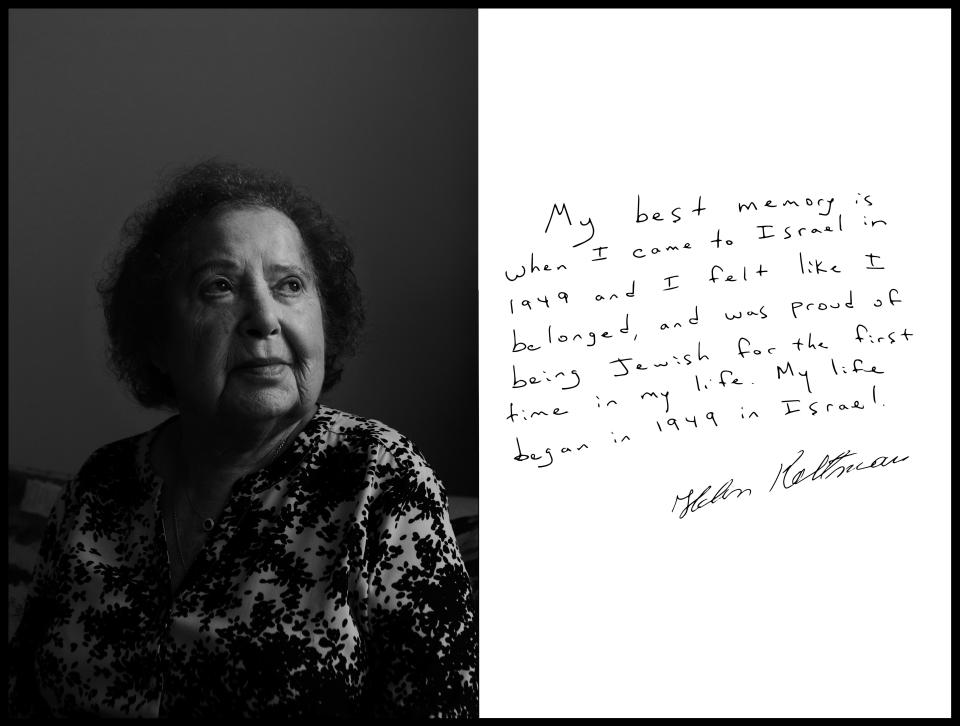

Helen Kaltman: “My best memory is when I came to Israel in 1949 and I felt like I belonged, and was proud of being Jewish for the first time in my life. My life began in 1949 in Israel.”

Helen Kaltman was born in 1937 in Warsaw, Poland. When the war began, she fled to the Soviet Union with her family. They first went to Siberia, where Helen’s mother had family. After a year they fled again to Uzbekistan. Helen’s father, Kissel, was drafted into the Soviet Army. Helen did not see her father until after the war. Her family went back to Poland after the war ended, but they experienced violence and antisemitism. Because they were afraid to leave their apartment, they were smuggled to Germany by Israelis to a Displaced Persons Camp. They spent four years in the DP camp before they immigrated to Israel in 1949. In Israel, Helen met another survivor, Simon Kaltman, whom she married in 1955. In 1959, Helen and Simon immigrated to Cincinnati to live near Simon’s brother Sam and his wife Roma.

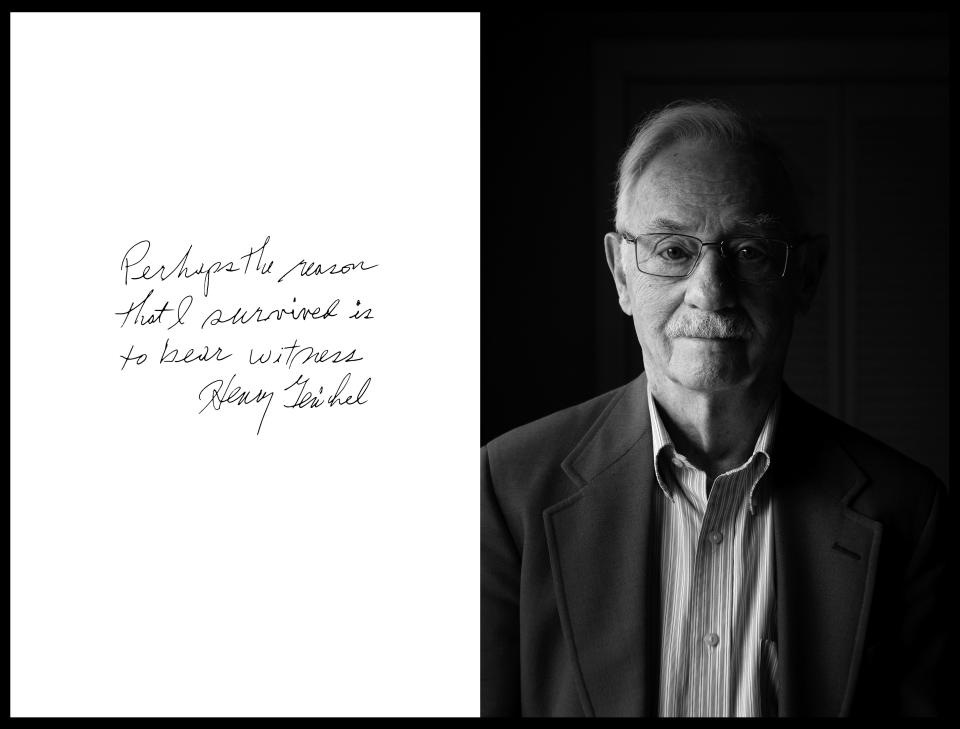

Henry Fenichel: “Perhaps the reason I survived is to bear witness.”

Henry Fenichel was born in April 1938, the Hague, Netherlands. Henry’s father, Moritz Fenichel, was born in Tarnow, Poland in 1903. When the German army occupied the Netherlands, Moritz was deported in July 1942 to Mauthausen, a concentration camp in Austria. Later, he was sent to Auschwitz, where he was murdered in November 1942. Henry and his mother Pessel hid from the Nazis, but in 1943, their Jewish identities were discovered. They were sent to Westerbrook, a transit camp in the Netherlands. Later, they were sent to Bergen-Belsen, a concentration camp in Northern Germany (the same camp where Anne Frank died in 1945.) Henry and his mother were saved by an exchange transfer to British mandate Palestine in 1944. In 1951, the two immigrated to the U.S. In 1965, Henry moved to Cincinnati, where he was a physics professor at UC for about 38 years.

To learn more about the Holocaust and survivors' lives once they arrived safely in Cincinnati, you can visit the Nancy and David Wolf Holocaust and Humanity Center at Union Terminal. It is open Thursday through Monday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

This article originally appeared on Cincinnati Enquirer: Live to tell: Holocaust survivors remember so others do not forget