Lively book tells fascinating tales of Civil War spycraft | DON NOBLE

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You might think that nothing new could be said about the American Civil War.

This turns out to be not altogether true. Alexander Rose has organized fascinating new information and has an enviably smooth prose style.

At the opening of the war, the Confederate arsenal consisted of “just 159,000 muskets, rifles and pistols, about 3 million cartridges,” and gunpowder “mostly left over from the Mexican War ….” There were enough bullets to provide 28 rounds per firearm — "barely sufficient for a soldier to fight a single battle.” One has read elsewhere that there were few facilities for making gunpowder, and Rose tells us the South could manufacture only 1,500 firearms per month.

President Abraham Lincoln called for a naval blockade and the Confederacy at first scoffed. After all, there were 3,549 miles of Confederate coastline.

Yes, but the Union did not need to blockade beaches and swamps and rocky coasts, only seven ports, from Norfolk, and Wilmington to Savannah, Charleston and New Orleans, Mobile and Galveston.

More:James Braziel tells stories of rough people in a rough place | DON NOBLE

The most startling piece of data, however, concerned the Confederate Navy. Total number of ships: one.

The South needed to obtain warships abroad, mainly in England, and pay for them with cotton. At first, this was actual cotton, then as time passed the collateral became cotton futures, promises of cotton that would be brought out by blockade runners who had brought in goods and then loaded up.

It was only near the end of the war that the Confederacy “nationalized” and controlled blockade running. For most of the conflict, the blockade runners, the Rhett Butlers of myth, were independent contractors. They brought in arms, but also the highly profitable wines, cigars, and finery that rich planters and their wives still craved.

The British mills truly needed that cotton, mountains of it. One-fifth of the British people were dependent in some way on the cotton industry.

And Southerners hoped, if the blockade could be proven ineffective, and if the South seemed to be winning, perhaps the Brits would recognize the Confederacy or, as many wished, actually take her side.

The English had fought and lost to the U.S. in 1776 and in 1812, so not everyone was on board with this idea, but some were. At first, the British felt the war was for Southern independence, but with the Emancipation Proclamation, that changed to a war to end slavery and British sympathy dwindled.

No doubt, cotton was indeed king. Rose quotes South Carolina Sen. James Hammond, who stated that the South “could bring the whole world to our feet” by cutting off the supply of cotton. Rose then, in a kind of aside, calls Hammond “an incestuous ephebophile, busy slave-rapist, and inadvertently amusing egomaniac.”

An ephebophile, one learns, is “an adult who engages in sexual activity with adolescents.”

To create a navy, the Confederacy sent a shrewd, in fact, slimy operator to Liverpool. This fox was James Bulloch. Under orders from Jefferson Davis, he would bribe and court the shipbuilders, pushing the limits of the arcane and complicated British laws concerning building ships for foreign powers. He was fairly successful. Bulloch managed to get several ships built — new, fast and steam-powered — including the one that would be renamed the “Alabama.” Under Capt. Raphael Semmes, that ship would wreak havoc in the Atlantic.

Bulloch was a super spy — clever and resourceful. He bought and sent home, clandestinely, loads of arms and even managed to plant a Confederate mole in the British foreign office.

His adversary, the American consul in Liverpool, Thomas Dudley, was determined to prevent any of this from happening.

Dudley was as righteous as Bulloch was dubious.

A Quaker from New Jersey, Dudley was ferociously anti-slavery and anti-Confederacy. He reported to Charles Henry Adams, the American minister to Great Britain, and together, with counter-spies and in law courts, they parried Bulloch and his schemes.

A good deal of this takes place in Liverpool, which Rose describes as the most depraved port in the western world, filled with drunks, prostitutes, con men, pickpockets, fences for stolen goods, pawnshops and murderers, with the highest homicide rate imaginable — 500 per year — around the same number as today’s Chicago, with one-sixth the population. Each morning, as in Charles Dickens’ “Bleak House,” people “roamed the docks” for corpses to search.

In Liverpool, the population density was 660,000 per square mile. In New York today it is only 27,000. In one area, 7,938 people were crammed into 811 houses.

Rose entertainingly lays out this four-year cat and mouse game.

Spoiler alert: The Union wins.

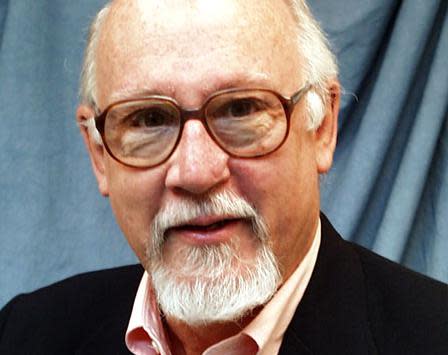

Don Noble’s newest book is Alabama Noir, a collection of original stories by Winston Groom, Ace Atkins, Carolyn Haines, Brad Watson, and eleven other Alabama authors.

“The Lion and the Fox: Two Rival Spies and the Secret Plot to Build a Confederate Navy”

Author: Alexander Rose

Publisher: Mariner Books

Pages: 270

Price: $28 (Hardcover)

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Lively book tells fascinating tales of Civil War spycraft | DON NOBLE