Living in Blythe: Amid city's fiscal struggles, residents see hope and opportunities

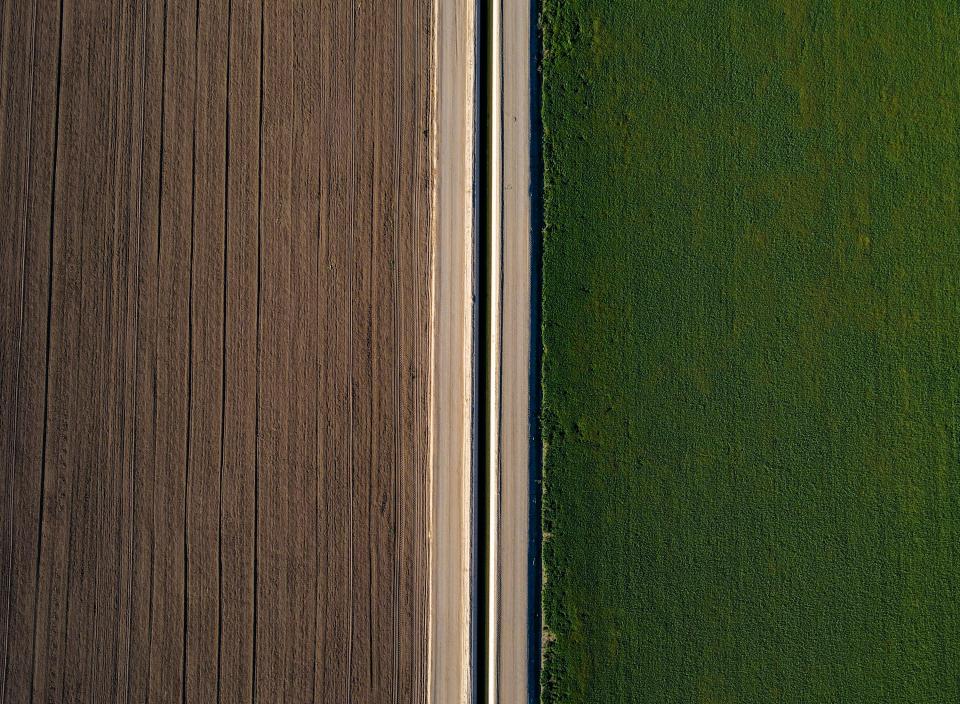

In the heart of the Sonoran Desert, nearly halfway between Los Angeles and Phoenix, the city of Blythe unfolds in a patchwork of green farmland from the western shore of the Colorado River amid the fertile Palo Verde Valley.

But according to the Riverside County Grand Jury, Blythe is terminally ill.

The city of approximately 17,000 is the county's most easterly and has long been the last pit stop for travelers before entering Arizona. Some consider the location cripplingly remote, while others value its seclusion and ruggedness.

For most of the desert city's nearly 110-year history, it's enjoyed unlikely agricultural success in large part due to its founder securing what became valuable rights to a significant share of the Colorado River's water.

But that legacy has been challenged and its future questioned as its residents have seen businesses shutter and the city government's finances falter.

In 2021 the California state auditor called Blythe's finances unsustainable, warning in a report that it had among the most at-risk city governments in the state and had not charted a clear fiscal path forward. Earlier this year, the grand jury followed suit, but added an eye-catching title in its report "City in Peril - Blythe is Dying."

That struck a nerve.

City officials acknowledge Blythe's fiscal struggles and say they've already made some progress in addressing them. But they add the tone of the grand jury report is counterproductive.

"City leaders have worked hard to revitalize the city and be an attractive place for new residents and developers," said Mallory Crecelius, the interim city manager. "The report does nothing to help the city achieve its goals."

Largely unheard in the report, too, are the thousands of people who live in Blythe, who are raising families or going to school or starting businesses there. A Desert Sun reporter and photographer spent time in the city to hear what some of them have to say.

Against the odds, preserving the family farm

From the beginning, Debra Keenan knew she wanted to commit her life to agriculture. Growing up in a farmhouse that sits like an island in the middle of 340 acres of Blythe farmland at the end of a dirt road, farming was in her blood.

She remembers following her dad out of the house past the massive nopal cactus and beyond the bulging oleander windbreak, to the fields of alfalfa, melons, cotton and wheat. It was hard work, but she liked it and it was a great way to spend time with her dad.

"It gave me a chance to hear his stories, even if he told the same ones over and over again," Keenan said. "He talked about his time driving a tank in the military, a period of time he served with Elvis Presley, and growing up potato farming in Idaho."

Keenan, 58, is the youngest of Wayne and Gloria Stroschein’s four children, and the one, as she describes it, who took to the family trade the most readily. Keenan now manages the family’s approximately 1,400 acres, land they’ve owned most of the time since her grandfather came from Idaho in 1946.

She’s both a Blythe native and a self-described outsider farmer who isn’t afraid to try new things. For example, for someone who lives hundreds of miles from the nearest open ocean, she’s unexpectedly fond of the benefits of seaweed to drylands farming.

It started when Keenan was working with her dad after school at the age of 5. Cotton farmers in the area were plagued by the pink bollworm, and to determine when to spray for the pest, a pheromone trap was set to attract them and approximate their population.

"The trap looked like a little spaceship, and I thought it was so cool," Keenan said. "I went home and in the best way I could I drafted a contract that said I would work for my dad for free as long as he paid for my school."

And that interest not only in growing but the scientific research helping enhance crop yields led to her studying and working at the University of California, in both Davis and Riverside.

That’s when she started to get a sense of how her ambition, her education and her gender rooted her in the fringe of the Palo Verde Valley’s booming farming industry.

"One of the biggest farmers in town told me that I was gonna fail in school," Keenan said. "He said that the only way to succeed in farming was to work for him. I told him no, I’m not gonna work for you."

She’s now a research scientist with a master’s degree and a thriving business working with some of the largest agricultural companies in the world on chemical and fertilizer applications — seaweed among them.

Her education and business has taken her all over the state and country, to leadership positions in organizations like the California Women for Agriculture and the National Alliance of Independent Crop Consultants.

But in 2012, when her father died, she came back to help her mother with the farm in Blythe. The operation had a lot of momentum, she said, the people who had worked closely with her father helped keep the transition smooth. It was when his right-hand man made the decision to retire, that she remembers the fear setting in a little.

"It was all on me at that point, to hire the right people and keep things working," Keenan said.

And to make matters worse, drought and population growth have wreaked havoc on Blythe’s lifeblood, the river that creates the town’s and state’s eastern border with Arizona. The Colorado River made Blythe and the valley into an oasis of desert agriculture for most of the last century, but those years are fading fast.

Keenan has all of the family’s 1,400 acres of farmland in the state’s fallow program, which saves water by essentially paying farmers to not farm. According to the contract, she can’t have even a speck of green on 35% of the 1,400 acres, and each year she rotates fields in and out of fallow.

The Colorado’s water has been fiercely fought over for as long as Keenan has been alive. But she said she’s never quite gotten used to the feeling of being at the whim of changing politics in seven states managing a shriveling snowpack.

But she has faith in her skill and her research. She’s proud of how her alfalfa is of particularly high quality, meeting a protein measurement deeming it useful for more than feeding livestock. She has long studied how to use additives that make it grow more leaf and less stem. The additive is derived from seaweed, which is plentiful and cheap. The "good old boys" who told her she’d never succeed think it’s all a joke.

"They call it snake oil," Keenan said. "But I keep telling them, I’m making protein. I’ll show them how to do it. But they won’t listen."

Amid all the barriers she’s faced in her career, all the extra work she puts in to try and keep the family farm alive, these local squabbles are the ones that test her patience the most.

"Ya, I get fired up, and I don’t like it," Keenan said. "I wasn’t raised like that."

She was raised in Blythe, and yet she still gets treated like an outsider in a region that’s grappling with a mindset she thinks is partially to blame for its uncertain future.

Driving up the dirt road to her property can feel so distant from everything, even from the city of Blythe’s struggles over its path forward. Keenan said that isolation makes it easy to get caught up in water politics, in state farm legislation, in agricultural research. But all of that is meaningless, she said, if she doesn’t have a grocery store to go to in town or the people who work for her don’t have a good school for their kids.

She feels pressure to keep her family’s legacy alive in a town they’ve called home for three quarters of a century. She wants the farm to succeed and she wants the town to succeed, two legacies intertwined since her grandparents arrived just after World War II ended.

"There’s a lot of history here, but the mindset has got to change," Keenan said. "Legacy is not about blood, it’s about how you impact humanity."

‘When the chips are down’

About 13 miles northeast of Keenan’s farm, Danielle Lara runs Blythe’s first cannabis dispensary, The Prime Leaf, with her brother Trevor. It’s a family business through and through, started by her father, Mike Ferrage, and his two cousins, who had experience with medical marijuana in Arizona.

And in the coming weeks the family is opening one of the first two dispensaries in Quartzite, Arizona, about 20 miles east of Blythe. Lara said she’s excited to expand now that The Prime Leaf has an established staff and clientele.

Currently, Blythe houses the open desert’s only dispensaries east of the Coachella Valley until Phoenix, and the one in Quartzite will be the only within about a 75-mile radius in Arizona.

Ferrage had several careers before landing on cannabis entrepreneur: car salesman, melon distributor. He was born and raised in Blythe as was his dad, who owned a clothing and jewelry store.

At 13, Ferrage started working for Fisher Ranch, one of the largest farmers in the Palo Verde Valley. He started his first business soon after: selling burritos, chips and drinks at a small food stand. After a stint selling Fords, he was looking for new opportunities and heard Blythe was considering allowing recreational cannabis sales. His cousins had already been in medical marijuana in Arizona, but recreational was a different story.

"We went through the whole process," Ferrage said of gaining a city license. "There was a lot of uncertainty at the time, and they turned us down at first. But eventually we persuaded them. They knew I was a community-minded person, and that we’re local. This is where our roots are."

They renovated a years-vacant storefront near the town’s Albertsons grocery store. August marked the dispensary’s third birthday.

And the family is eager to share its success with the community. They raised some $23,000 that went to the city’s recreation center and the little league, among others. And were able to raise about $15,000 to help struggling businesses through the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I mean, the amount of money we were able to help with isn’t life-changing, but it definitely helped some people who needed it," Ferrage said.

He’s happy to support the fighting spirit to survive that he believes is a natural characteristic of people who live in a remote desert town like Blythe. For Ferrage, the city leadership’s financial hardships are just the latest in a string of challenges residents will rise to overcome: "When the chips are down, Blythe survives."

Welcoming new industries, like cannabis, is one way the city has to continue to adapt to remain vital, he said. To him the next step could be music and the arts, marketing Blythe as a town where people can live cheaply and have the freedom to explore new ventures and ideas.

"We’re not in demand right now," Ferrage said. "Businesses are leaving California for markets they can compete better in. To create demand here, we’ve got to be more inviting. The way I look at it, we’re in the middle of everywhere. And we need to help people see that."

He remembers when the road to Phoenix ran right through the heart of downtown, not the Interstate 10 that catapults drivers past Blythe on their way through the desert. Maybe Blythe will never be “quaint” like it used to be, Ferrage said, but its future can both embrace its historic and inviting small-town character while exploring new reasons for people to not only stop on their way elsewhere, but to stay awhile.

"We’ve got to clean up some of these buildings, work on curb appeal and reimagine what Blythe can be," Ferrage said. "It’s still a cheap place to live and spend time by the river. It can be attractive to all kinds of people."

Lara, who is raising her son Chase in Blythe, agrees the town has a lot to offer. But as a mother, she’s acutely aware of its more unfortunate hazards, like a growing wariness about crime.

"When I was a kid growing up here, I could walk to the grocery store by myself," Lara said. "But I wouldn’t let my son do that."

Chase Lara, 11, is in the sixth grade at Margaret White Elementary School, which offers classes through eighth grade. He likes writing and playing baseball and football. He rides his BMX bike and explores canal roads on a motorized go-kart he got from his uncle. His mom takes him out of town about every month, to visit her dad’s house in Phoenix or her sister in San Diego, where they can eat at restaurants and shop in stores they don’t have in Blythe.

It’s the lack of access to certain staple stores that Danielle Lara says can make living in Blythe a hassle. She remembers right around the time of the Great Recession, many family-owned, small businesses shuttered. KMart was the only big outlet store for years, until it finally closed in 2017. Lara said it was one of the only places to get essential, everyday items.

"That was where a lot of people did their Christmas shopping," she added. "When it closed, that was a shock."

The scant business environment in Blythe does emphasize the kind of independence and self-sufficiency that has long been a defining characteristic of the town, Lara said. She trusts that Chase has the same resilience that growing up here instilled in her, even if it’s a little more difficult on this younger generation.

"Before we had a movie theater and a bowling alley, a Pizza Hut with an arcade where we hosted birthday parties and celebrations," Lara said. "I definitely wish there were more opportunities here for him and other kids. But they’re strong and they find ways to have fun."

Serving up second chances

Stacy Rene Davis had a lot of different careers before she decided to open Blythe’s only Southern food restaurant a few years ago, and still works several jobs to make ends meet.

She worked in rehabilitation and as a counselor for people serving life sentences at nearby Ironwood Prison. She’s still a substitute teacher, tax preparer and notary. But cooking was in her blood, and it all started in her home’s kitchen.

"Someone told me: If what you do is sleep, eat, and dream cooking, then you should be a cook," Davis said. "My heart’s in cooking."

She was accepted in 2019 by the Riverside County Department of Environmental Health’s Microenterprise Home Kitchen Operation program, which helped her bypass some of the challenges of opening a restaurant. Through the program she was able to promote dinners cooked in her own kitchen for friends and family and keep perfecting her craft, one that is deeply rooted in her commitment to service.

Her father was a pastor near Oceanside, where she grew up, who often enlisted her to help feed the community and those experiencing homelessness. Her cooking style is a combination of his ribs and greens; her mom’s mac and cheese; and a variety of her grandmother's dishes. All suffused with her family’s Memphis roots.

She moved to Blythe from San Diego County in 2011 to help start a women’s transitional facility, before working at the prison along with other odd jobs. But 2019 is when she first attempted to realize her calling.

"I started at the city, I told them: 'I want to do this, but I really don’t know how,'" Davis said. "'Tell me what I need to do.'"

She saved the extra money she made as a tax preparer for a couple years and rented a dilapidated storefront that had once housed a restaurant. Some city workers guided her in the right direction on paperwork and inspections.

"Everything was really dusty. There were these huge ceiling fans, lots of black paint," Davis said. "People from my church helped me clean it up. And the city inspector let me do some trial runs, where I cooked for friends for donations."

For months, she kept practicing her craft as she got the restaurant into shape to pass inspection, which it finally did days before Stacy’s Kitchen opened in March of this year.

In addition to all her other responsibilities, Davis is a trustee on the board of Palo Verde Valley College, where she befriended the board’s President Stella Camargo-Styers, who is not only a booster of the town’s thriving community college but of Davis. Camargo-Styers got to know her during the time she was working through renovations and inspections.

"At the time, there were a lot of businesses that weren’t opening in Blythe. Just to have another restaurant in Blythe was a huge deal," Camargo-Styers said. "I’ve owned businesses here and my parents did too. You’ve gotta have two or three jobs to make it work sometimes. You've gotta be universal. Stacy has a very strong will. She has a lot of faith in her prayer and faith in making it happen."

Camargo-Styers ordered a hamburger on a recent Wednesday night when the restaurant was just beginning to fill up for the evening’s dinner. Davis threw in some chili, which to her surprise has been a top seller.

"I served chili at first to keep people occupied while I was cooking," Davis said. "But now people come in just for my chili and cornbread special."

She changes the menu from time to time to follow her creative impulses, but the staples stick around: meatloaf, “real home” fried chicken, brisket and pork sandwiches, mashed potatoes, greens, cornbread, fried catfish, dirty rice and mac and cheese.

For Davis, cooking and community are intertwined, she said. She knows how important it is to get an opportunity to work. She said Blythe’s struggles center on a lack of opportunities for people to develop skills that will help them to open small businesses like she did.

Nearly everybody who Davis employs is a former addict or had been previously incarcerated, and she works hard to help them learn the skills needed to change their lives.

"A lot of times society puts different people in boxes," said Davis. "Some people look around and think: he’s a bum. But people change and they need help doing that. I had no clue either, but I figured it out. There’s some teaching going on while I’m here cooking. How to be responsible is the biggest part of what I’m teaching. Not enough people are telling them: you can’t do less than your best."

Coming home — and going places

It’s a slow day at the Joe Wine Recreation Center and already about 25 kids are taking turns playing video games, shooting hoops on the basketball court and sparring at the air hockey table.

Supervisor Cristina Crowe says that on summer days some 150 kids will pack the center to fight the monotony of staying home when temperatures outside can reach 120 degrees.

Crowe, 37, grew up in nearby Ripley and would take the bus into Blythe to go to class and practice as a student athlete. She now manages the city-run center’s staff of seven and is also the youth sports coordinator, overseeing leagues for soccer, flag football and cheer.

"Some of these kids have been through a lot," Crowe said. "But most of them are doing a good job staying out of trouble and keeping busy."

A mother plays Connect 4 with her daughter at a nearby table while Joey Williams serves a couple kids ice creams from the snack bar before they run to play video games.

"I know why I’m here: PlayStation 4," one of the kids says before running to one of the video game stations.

Williams, 32, attends Palo Verde College, but he’s been coming to the recreation center since he first moved to Blythe from Riverside in 2003.

"When I moved, I asked other kids: what do you even do out here? They said: We go to the rec," Williams said. "This was one of the only things I really liked to do for a long time."

Julian Vaca, 19, also attends Palo Verde College, the local community college, where he’s studying criminal justice. He’s a staff member at the center monitoring things from its main desk in the back corner and going out to the center’s six basketball hoops. He was born and raised in Blythe and met Jonathan "Jonny" Crowe, Cristina’s son, at the recreation center when they were about 14.

Crowe’s a senior at Palo Verde High School, a Cavaliers fan and a self-described "sneakerhead." He swung by the center before practice to trade shots at the basketball hoop with his mom, and talk about retro Nikes with Vaca.

He’s meeting the goals he’s set for himself on the school’s football team: one sack and four tackles a game on the defensive line and seven carries averaging seven yards a carry at fullback. He’s clocked 10.5 sacks and improved to 9.5 yards a carry in the team’s first nine games.

"I’ve been happy with how I’ve been playing," Crowe said with a smile.

Crowe is new to the team this season but not to the town. He grew up in Blythe but moved to Palm Desert just before freshman year to live with his grandmother, Kellie Williams Crowe, who moved there after she retired from her job at Chuckwalla State Prison.

"It was hard," Cristina said of the move. "But we thought it would be better for him, more opportunities."

Jonny said he remembers the conversations well: "At first, I was up for it, but then as it got closer, I started getting pretty nervous. I just didn’t know what to expect."

"Go for a year, and if you like it, stay," Cristina Crowe said they finally agreed.

Crowe took well to the team at Palm Desert and made an impression as an under-the-radar counterpart to the notorious players the team already had at defensive line. And he also started on the offensive line when needed. But Crowe’s time on the Aztecs was cut short when his grandmother died last winter. The family made the difficult decision to bring him back to Blythe.

"I grew close to my teammates out there, and I still text them," Crowe said. "But coming back wasn’t so hard, I already knew most of the players here."

Cristina Crowe is proud of her son’s success in sports but worries a bit about what might be next for him. She hoped in Palm Desert he could garner some attention that might open doors for him in college sports. While not impossible here, it just seems a little harder for hardworking kids like him in out-of-the-way places like Blythe.

And it troubles her that athletes can get preferential treatment if, for example, their grades are struggling. Cristina Crowe thinks there’s little changes that could help the local kids out.

"I want computers for the kids to do homework on," Crowe said. "They have Chromebooks at school, but they can’t take them home. In Palm Desert, they could, but not here."

Jonny Crowe’s skills are being noticed noticed in Blythe. He received his first offer from a college football team, Arizona Christian University, and is hoping he’ll hear from more in the near future. He said he’s staying focused and positive, much like many of the other young people who flock to the recreation center. It’s an optimism rooted in community that he’s carried with him from town to town in the desert, through wins and losses, and one that illuminates his path forward.

"No matter where you’re at, you’re part of the team," Crowe said. "And whenever anybody’s struggling we gotta pick each other up."

Christopher Damien covers public safety and the criminal justice system. He can be reached at christopher.damien@desertsun.com or follow him at @chris_a_damien.

Editor's note: A previous version of this article included an incorrect last name for Stella Camargo-Styers.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Living in Blythe: Amid fiscal struggles, residents see opportunities