Lloyd Austin’s preference for a low profile was seen as an asset by the White House — until now

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

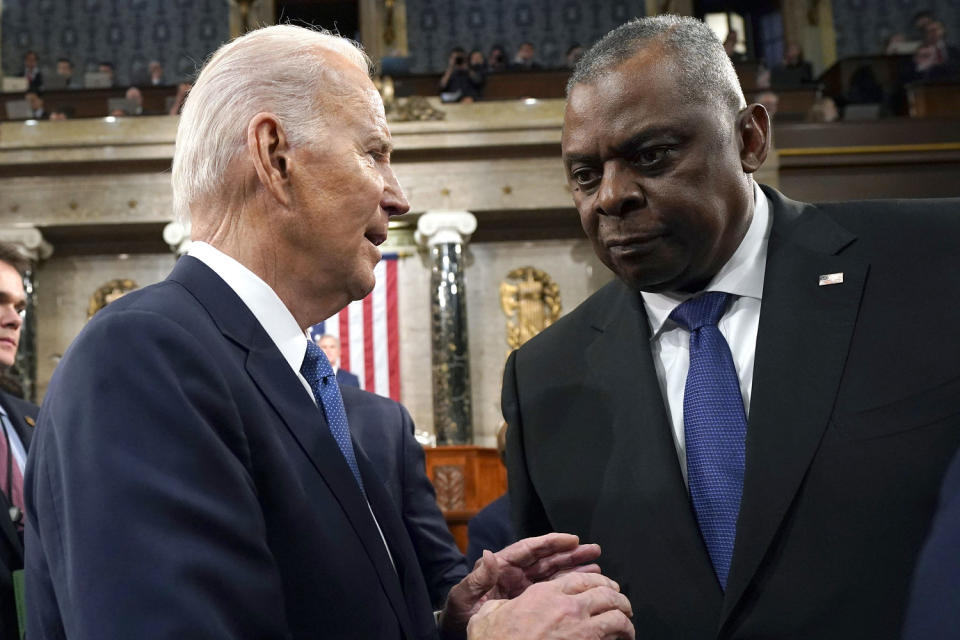

As an Army officer and as defense secretary, Lloyd Austin has earned a reputation as a man of few words who tries to avoid the public spotlight, a trait that the White House saw as a plus — until now.

Austin’s desire to maintain a strictly low profile has now backfired badly after he failed to inform the White House for several days that he had been rushed to a hospital on New Year’s Day because of complications from prostate cancer treatment.

His reticence about his medical condition has created a political headache for the Biden administration and angered lawmakers from both parties, who are demanding to know why the secretary and his senior staff kept the president in the dark about his stay in the intensive care unit at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

The White House has said President Joe Biden has full confidence in Austin, and officials have said the president does not plan to fire him or accept any offer to resign.

Inside the White House, from Biden’s top advisers to the president himself, Austin’s understated public demeanor has been viewed as an asset, particularly for a team that loathes leaks and drama. But, some officials said, sometimes an asset can turn into a liability. And, they say, that’s what happened in this instance with Austin.

A former senior military officer and friend of Austin's described him as an introvert, a “good, decent guy without a dishonest bone in his body.”

While the former officer did not believe Austin should be fired, they said the lack of disclosure about his condition and hospitalization was inexcusable.

“He’s a private guy, but he’s also the secretary of defense,” the person said.

Peter Feaver, a professor of political science at Duke University, who has written extensively about civilian-military relations, said that “while the desire for privacy is understandable, it’s not a privilege that you can have when you’re the civilian in the nuclear chain of command.”

Feaver said it was an “egregious mistake” for Austin not to inform the president, the national security adviser and the White House chief of staff about his condition.

Throughout his career, Austin, now 70, has been a quiet, understated figure. Unlike some generals who relish public speaking and pushing back against opposing views, Austin favored working behind closed doors without fanfare.

When he was head of Central Command as a four-star general, overseeing American troops in the Middle East fighting a U.S.-led war against the Islamic State terrorist group, Austin rarely spoke to reporters.

During his CENTCOM tenure, when he was scheduled to speak at a 2014 Washington event organized by the Atlantic Council think tank, Austin insisted that there be no television cameras in the room.

For Biden and his team, Austin’s reserve was seen as a strength when he was picked to serve as defense secretary. Keen to avoid a “team of rivals” Cabinet, they believed that some generals and Pentagon officials had undermined President Barack Obama, such as when they briefed reporters and lawmakers in a bid to pressure the president over whether to send more troops to Afghanistan, former officials say.

Having worked closely with Austin during his time in uniform, Biden and his aides viewed the retired general as a loyal, steady hand who would not undercut the White House and who shared the president’s cautious view about resorting to military action.

When Biden decided to withdraw American troops from Afghanistan in 2021, he rejected the advice of military commanders and Austin to retain a smaller force. But Austin carried out the decision without friction and kept a lid on any criticism from the Pentagon.

Administration officials also have praised Austin’s role in rallying support from NATO members and other countries to provide more weapons to Ukraine.

‘Could have done a better job’

But Austin became the unwanted center of attention in recent days, frustrating some top White House officials over what they view as an unnecessary, self-inflicted error by the secretary and his staff.

On Dec. 22, Austin went to Walter Reed to undergo a surgical procedure for prostate cancer and returned home the next morning. But within days, Austin had “severe abdominal, hip, and leg pain” and nausea, and had to be taken back to the hospital by ambulance on Monday, Jan. 1, according to his doctors.

Austin was transferred to the intensive care unit, having developed complications from the earlier procedure, including a urinary tract infection and a backup of abdominal fluid that impaired the function of his small intestines. Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks was told to assume Austin’s duties on Tuesday, Jan. 2, but was not told why, according to Pentagon officials.

It was not until Thursday, Jan. 4, when Austin was due to attend an event at nearby Joint Base Myer-Henderson Hall, that Austin’s chief of staff, Kelly Magsamen, told White House national security adviser Jake Sullivan and his deputy, Jon Finer, that the secretary had been in the hospital since Monday evening, according to Biden administration officials. Sullivan informed the president, the White House chief of staff and White House counsel.

Even then, the Pentagon had no plan to issue a public statement or to inform members of Congress, administration officials said, and no one around Austin seemed to understand the need to disclose his medical condition. Sullivan and White House chief of staff Jeff Zients demanded they issue a statement after Austin’s hospitalization on Thursday, according to officials.

The next day, the Pentagon released a statement revealing that Austin had been in the hospital all week because of complications from an undisclosed medical procedure. The Pentagon also said Austin had resumed his duties as secretary.

On Saturday, Jan. 6, Austin said in a statement that he “could have done a better job ensuring the public was appropriately informed” and “took full responsibility for my decisions about disclosure.” That same day, Austin spoke with Biden for the first time since his hospitalization. Two people familiar with the call said the secretary sounded groggy at the time. And it was not until Tuesday, Jan. 9, that Austin disclosed his medical diagnosis of prostate cancer —which his aides said was made in early December — to the president and the public.

Both Democrats and Republicans have sharply criticized Austin and the Pentagon in recent days, urging a full explanation of why the secretary’s condition was kept secret from the White House and lawmakers.

On Wednesday, Rep. Chris Deluzio of Pennsylvania became the first Democrat to call for Austin’s resignation.

“I have lost trust in Secretary Lloyd Austin’s leadership of the Defense Department due to the lack of transparency about his recent medical treatment and its impact on the continuity of the chain of command,” Deluzio said in a statement.

The chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Republican Rep. Mike Rogers of Alabama, has announced a formal investigation into Austin’s hospitalization, demanding a detailed account from the Pentagon about what medications Austin received, what official decisions he has made since Jan. 1 and all written communication between his office and the White House.

Not only Austin but his chief of staff and other aides are now under intense congressional scrutiny over their role, with growing questions about why they did not immediately alert the White House about his condition.

Although Austin is still recovering in the hospital, the Pentagon says he is “fully engaged” in his work and has received regular updates from senior military officers, including the head of Central Command, Gen. Michael “Erik” Kurilla.

At some point, Austin may be forced to face a high-profile grilling from lawmakers, but his previously closed-lipped approach means he may lack strong allies on the Hill.

“One of the lessons in Washington civil-military relations is you have got to build the trust when you don’t need it, so it’s there when you do need it,” Feaver said.

Austin has been less than forthcoming compared with his predecessors. But from now on, “I suspect he is going to have a slightly more forward-leaning public engagement,” Feaver said.

The defense secretary’s former colleagues say his long, successful career should not be judged by this single episode. Austin, who grew up in Georgia when segregation was still in place, is the country’s first African American defense secretary. He attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in the 1970s, at a time when Black officers were rare.

“This kid from south Georgia went to the U.S. Military Academy when there were almost no Black people at that level in the U.S. military. Every step along the way he’s a success,” said the former military officer.

“But I also used to think about the horrible pressures he must have been under — both personal and professional — that I never experienced. There was an extra weight” that Austin carried as a Black man rising within a largely white institution, the former military officer said.

In May, Austin spoke of his youth in the segregated South at an event in North Carolina.

“I grew up in Georgia in the time of Jim Crow. Our local public high school had long been all white,” Austin said at Fayetteville State University. “And one of my sisters and I were among the first Black students to integrate it.”

“Those were pretty ugly days,” he said. “And the first year was especially tough.”

Austin recalled the teachers, school leaders and officials who upheld the American principle that all people are created equal, praising their “quiet resolve.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com