Local Big Brothers Big Sisters branch closes with no alternative for members. What now?

When Garen Haddad walked through the doors of the Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Mid-South office in 1998, he wasn’t exactly a model citizen. After a mild dust-up with the law, he had been required to complete community service hours, and he had decided to volunteer with the mentorship-focused nonprofit.

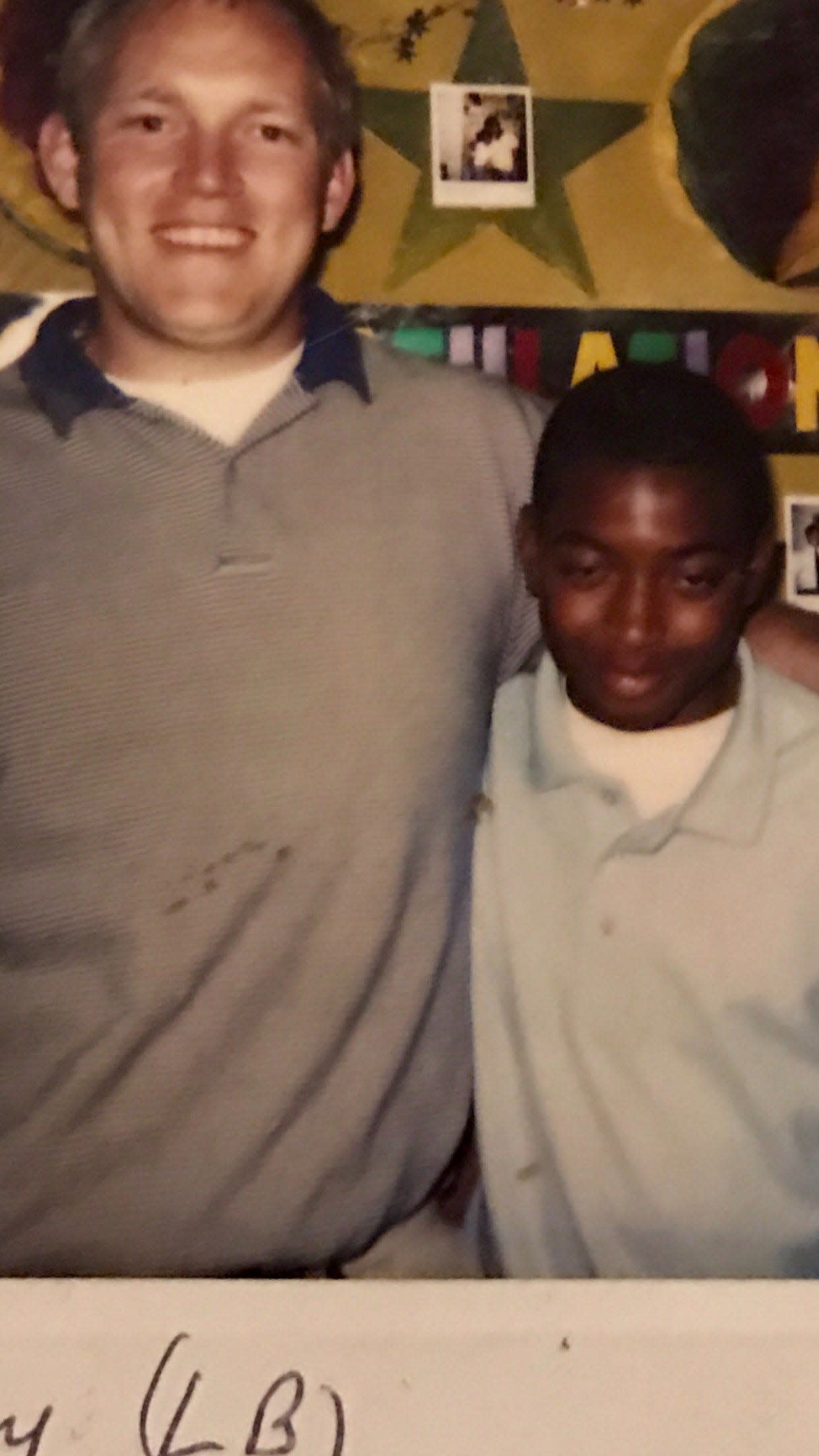

But when BBBS of the Mid-South matched him with 11-year-old Jeremy Whittaker, who was being raised by his mother, he decided to better himself. Haddad didn’t know what it meant to be a mentor. But he knew that Whittaker looked up at him, and he wanted to “walk the talk, rather than just talk the talk.”

“By nature of him looking at me, I cleaned up my act," said Haddad, who would serve on BBBS of the Mid-South's board from 2003 to 2017.

He also acted as an older brother to Whittaker, living up to the name of the nonprofit. He tossed the football with him in the backyard and took him to sporting events. He showed him how to barbecue and tie a tie. He helped him get into Christian Brothers High School ― his alma mater ― and discussed career possibilities.

But he did more than this. He allowed his mentee into his life, “not with a picture of perfection,” Whittaker said, “but a picture of genuine progression.”

The two became family, and as time passed, Whittaker reached adulthood and pursued his own academic and career goals, with the support of Haddad. Today, Whittaker has a doctorate and is the associate dean for student success and inclusion at the University of Memphis’ Loewenberg College of Nursing, and he’s remained close with his “big brother.”

The relationship between him and Haddad has been life-changing for both of them. And it’s a relationship that started because BBBS of the Mid-South connected the two nearly 30 years ago.

As Whittaker put it: “Big Brothers Big Sisters was the vehicle that made that magic moment that went on for a lifetime.”

But recently, Haddad and Whittaker heard dismaying news about the organization: after decades of matching children seeking mentorship with adults that can serve as their “big brothers” and “big sisters,” BBBS of the Mid-South had shut its doors.

'We regret to inform you'

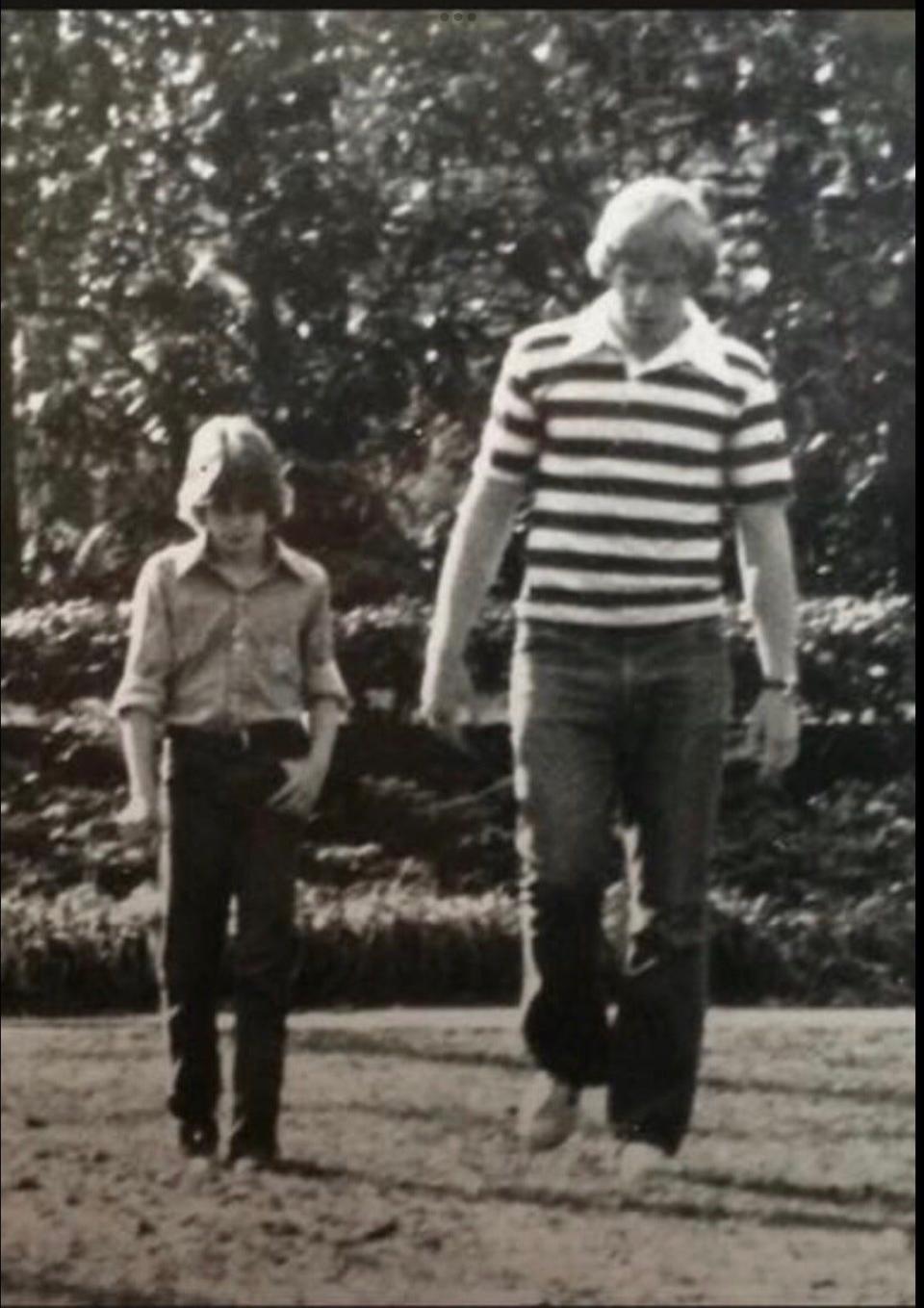

Forty-eight years ago, Chris Thomas’ mother signed him up to participate in BBBS of the Mid-South’s flagship program. He was 11 years old, and he was matched with 18-year-old Mike Edwards, who played football at Rhodes College. Flashforward to the present, and Thomas ― who has remained close to Edwards ― is now involved with the program by serving as a “big brother” for a boy named Casey.

The two love sports and Thomas has both taken Casey to professional matches and attended his own games. He’s taken him to movies and the Stax Museum of American Music, and Casey’s mother has told Thomas that the relationship has helped her son.

In mid-October, however, Thomas got a letter from Big Brothers Big Sisters of America, the national mentorship mentoring network BBBS of the Mid-South is affiliated with, which said the local nonprofit had closed ― and that mentors should freeze contact with their mentees.

“We regret to inform you that Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Mid-South is no longer authorized to operate a Big Brothers Big Sisters program,” it read. “Due to the closure of the Mid-South program, effective immediately, the match between you and your Little will no longer be active in the Big Brother Big Sister program management system, nor will the match be provided professional support services. We recommend that you immediately pause contact with your Little.”

The letter went on to say that any future contact between Bigs and Littles would “be at the risk of the parties involved,” and that the goal was for BBBS of America to bring the program back to the Mid-South in the near future.

Thomas has chosen to continue his relationship with Casey despite the letter’s recommendation, but BBBA of the Mid-South’s closure has troubled him. The juvenile crime rate in Memphis is high. The child poverty rate is above 30%. The loss of a longtime mentorship program, he believes, is far from ideal.

“This is not a time we need to be walking away from being mentors,” he said. “We need to step it up.”

He’s also wondered why the organization closed.

“It’s very puzzling to me, the more I think about this,” he said. “What happened?”

'A lot of balls in the air'

After learning that BBBS of the Mid-South had closed, The Commercial Appeal reached out to BBBS of America, which provided the following statement:

“Big Brothers Big Sisters of America is aware that BBBS of the Mid-South in Memphis, TN was no longer an active affiliate as of September 1. BBBSA understands and appreciates the role that BBBS of the Mid-South has played in Memphis and hopes to find an opportunity to continue serving the community in the near future.”

Exactly why the organization shut down and how many mentees were affected by the closure is unclear. Susan George, BBBS of the Mid-South’s executive director, didn’t respond to multiple requests for an interview. And though the organization’s website does say that it “currently serves over 680 youth,” it also says the chairman of the board is Christopher Hearn ― who told The CA he hadn’t been on the board in about two years.

From Thomas’ perspective, BBBS of the Mid-South had been less engaged with its mentors and mentees recently. The organization typically provides support services for its Bigs and Littles, but Thomas said it’s been at least six months since he had heard from a staffer, and previously, someone would have checked in on the match every two months.

He also isn’t sure the organization has been as proactive about fundraising in the last few years as it has in the past. And fundraising is one of many important areas a nonprofit like BBBS of the Mid-South must have success in.

The CA spoke to Adrienne Bailey ― wife of the late judge and civil rights activist D’Army Bailey ― who spent 20 years as the group’s executive director, before retiring in 2015. Running the nonprofit, she explained, was extraordinarily rewarding, but far from easy.

And it takes a lot to keep everything running smoothly.

“All cylinders have to go in the same direction at the same time, and that's difficult because there's a lot of balls in the air,” she said. “You're dealing with children's lives, volunteers’ lives, parents' and guardians’ lives. That's a lot, and there’s always a risk and a liability. And then you’ve got to convince supporters and funders to believe in it and invest in it.”

Bailey stepped down from her role after her husband’s death eight years ago. But when asked why she thought BBBS of the Mid-South might have closed, she said funding likely played into it, as running the organization isn’t cheap. It had to pay dues, she said, to BBBS of America, as one of its affiliates. It had to maintain its facility, pay staff, ensure children in the program were safe, and cover insurance costs ― which, she said, “were out of the roof” when she was running the organization.

This meant that securing ample amounts of funding was key.

The most recent public financial data about BBBS of the Mid-South is from the organization’s 2019 Form 990. That year, it earned $353,879 in revenue and had $499,924 in expenses, leaving it with a net loss of $146,045. While this type of number isn’t one that guarantees doom for a nonprofit, it was the third consecutive year the organization had recorded a loss, and its total assets had dwindled over time.

In 2012, the organization had $682,496 in total assets. By 2019, that number was down to $52,002.

“The economy is just crazy,” Bailey said. “We had COVID. So many barriers started popping up, and I don’t think the organization was resilient enough to support it.”

A community need

For Bailey, the closure of BBBS of the Mid-South was heartbreaking. She had championed the organization for two decades and helped turn it into a thriving nonprofit. She considers it, she said, “her life’s work.” And she can remember people coming to see her, years after their time as mentees, to tell her how much they had been impacted by the organization ― which leads to one of her concerns about its absence.

"The gangs and groups that are not doing the work that could be done in a good way to work with children, they're out there now… kids are going to be mentored, good mentoring and bad mentoring,” she said.

She’s also far from the only one who believes there’s a need for the nonprofit ― and others like it ― in the community. Just about everyone The CA spoke to expressed the importance of the mentorship BBBS of the Mid-South provided.

“It’s very unfortunate because we know we need mentors in the Memphis area in a big way,” said Mike Edwards, Thomas’ “Big Brother,” who was also the organization’s board chair in the 1980s. “Big Brothers and Big Sisters obviously, had a proven track record for decades.”

Added Haddad: “It would be a hell of a loss for our community.”

Haddad and others, however, are hopeful that it will be revived, just as BBBS of America hopes it will be re-established in the Memphis area. And Raumesh Akbari, a Memphian and the minority leader in the Tennessee Senate, shared her support for the organization, noting that representatives from it have spoken to the state in the past.

“They oftentimes are the difference makers, when you're talking about changing the trajectory of someone's life,” she said. “And I'm hoping that we'll be able to give them the resources they need to make sure that they continue to do this work.”

For now, however, the organization is closed. And as Haddad has reflected on his years with BBBS of the Mid-South, he’s thought back to the birth of his first son, Carsten, and when Whittaker, his “little brother” in the program, held him for the first time.

As Whittaker cradled Haddad’s son in his arms, he began to cry.

“You’re good,” Haddad told him encouragingly. “Carsten’s good. You’re not hurting him.”

“No, Garen, you don’t understand,” Whittaker replied, teary-eyed. “Now I get to be a big brother, to Carsten.”

As time has passed, Whittaker has served as a mentor to both Carsten and his brother Logan. To them, he’s “Uncle Jeremy,” and he’s been able to impact their lives, just as Haddad impacted his.

“That story is really what I think encapsulates Big Brothers Big Sisters,” Haddad said. “And I'm quite certain that if, given the opportunity, this community will once again throw incredible support around it. It's too important to fail.”

This article originally appeared on Memphis Commercial Appeal: What happens now Big Brothers Big Sisters of the Mid-South closed?