Local history: The bell tolled in 1866 for the Tri-State’s worst steamboat disaster

We’ll never know exactly how many people were killed in the Tri-State’s deadliest steamboat disaster.

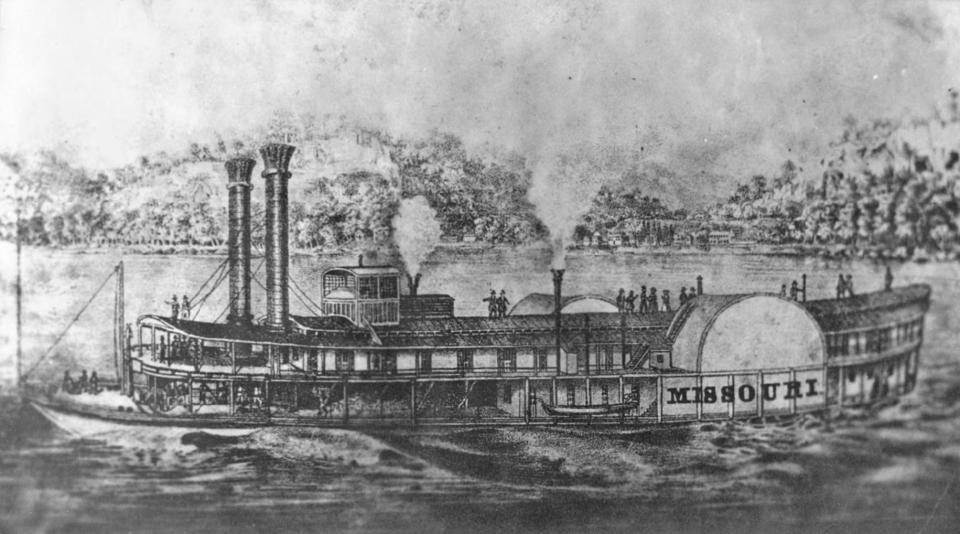

The Missouri was a relatively new boat that was 306 feet long and 42 feet wide. That’s longer than a football field if you discount the end zones. It had been built in Cincinnati in the spring of 1864 and its captain, Jesse Y. Hurd, was majority owner. It exploded near the mouth of the Green River at 2:10 a.m. Jan. 30, 1866.

We often think of steamboats as graceful works of art – and they are – but during the heyday of the steamboat age they frequently led brief and dangerous lives. A U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report for 1866-67 noted there were 18 derelicts blocking the river between Louisville and Cairo. The Missouri was one of them.

Snags and boiler explosions were the worst culprits. The latter is what did in the Missouri. The explosion “rattled windows and doors” in Evansville, according to the Jan. 31 Evansville Daily Journal, and presumably also in Henderson.

The first rescuers on the scene were from the Dictator, which had left Evansville about the same time as the Missouri. There was some talk that the two steamboats had been racing; more about that in a moment.

Henderson history: Anaconda’s first aluminum potline fired up back in 1973

The Dictator’s crew rescued what people it could, and then stopped at Newburgh to take on a couple of doctors, who stayed with the injured as far as Cannelton, before the boat proceeded upriver. Upon arriving in Louisville, approximately 25 of the survivors published a card of thanks praising their rescuers, according to the Feb. 2 issue of the Indianapolis Daily Herald.

That same issue included the tale of Indianapolis resident J.S. Fatout, who “awoke to find himself buried beneath a mass of shattered timbers, the forward cabin on fire, and the groans of the dying on every hand.”

He worked his way through the wreckage to the upper deck, where he was rescued by people from the Dictator. “He was considerably bruised by the falling timbers but is otherwise uninjured.”

Fatout was extremely fortunate. The Evansville Daily Journal’s account of Jan. 31 says, “From Mr. Roberts, who was at Newburgh when the Dictator landed there, we learn that many of the passengers and crew of the Missouri were terribly scalded and mangled.

“All the hands and officers on the lower deck were reported to have been lost – not a soul escaping. It was estimated that at least 100 lives were destroyed by the terrible calamity.”

(The same story provides an exact time for the accident: “The hands of the clock that we fished out of the wreck indicated 10 minutes after 2.”)

A story from the Evansville Courier that was republished in the Hendricks County Union of Danville, Indiana, on Feb. 22 indicates there may have been another rescue effort. Adam B. Linegar, a fisherman who lived on the point where the Green and the Ohio merge, was roused by the explosion.

Linegar, “imperfectly clad, jumped into his little craft and struck out in the dark river guided by the cries of those unfortunate men struggling for life.” His efforts “saved from the unpitying waters 32 souls.”

If I sound a bit skeptical, it’s because there was no word about where Linegar transported the victims.

The Evansville Journal’s reporter made multiple trips to the wreck site for that first story, so several updates were tacked on the end of it. Here’s how the coverage began:

Evansville and Henderson residents woke the morning of the explosion to find wreckage floating past their riverfronts.

“The steamer Charmer lying at the wharf immediately got up steam and, with a large number of our citizens on board, started for the wreck,” the Journal reported. The Missouri had floated down to the foot of Green River Island (about where Inland Marina is currently located) and lodged there. Upon reaching it, those aboard the Charmer “beheld a sight calculated to freeze the blood.”

The only body they could find was that of the captain’s wife, Catherine Hurd, who was badly mangled but remained recognizable. (The captain’s eldest son, pilot Henry Hurd, suffered a badly broken leg and died in Portsmouth, Ohio, according to the Feb. 7 Journal.)

Local life: Stopping the 'madman': Rockport, Indiana woman to appear in PBS Vietnam documentary

The boat had broken in two and sunk, with the bow and stern both elevated into the air. A careful search found not a soul aboard to tell the tale, although the officers of the Charmer recovered several packages of money. (A later steamboat recovered the safe with more than $10,000 in it.)

The Charmer then returned to Evansville for equipment to recover more efficiently what could be salvaged. By the time it returned most of the boat was under water. “We saw traces of blood, indicating that mangled and bleeding persons had been taken from their cabins through windows and holes in the roof.”

They made a thorough search for the passenger manifest and a list of officers and crew, but were only partially successful. The crew list was recovered and published, but no record of passengers was ever found. Without it, only estimates can be made of how many people died.

The official estimate is 65, but several newspapers at the time reported it at 100 or more.

“It is also stated four passengers got aboard at Henderson and six at Evansville, all of whom are supposed to be lost,” the Journal reported.

“The Missouri was valued at $125,000 and had, as we are informed, no insurance. She is the third boat of the Atlantic & Mississippi Line of steamers which has been lost within two months.”

Way’s Packet Directory reports the racing allegation – and worse. The first engineer, Jim Phillips, had written to his brother in Wheeling, West Virginia, and said he thought the tubular boilers were unsafe and that he planned to resign in Louisville. (Other boats with tubular boilers were also exploding about that time, which prompted the federal government to quickly ban them.)

The Evansville Courier also publicized the racing allegation, which I’ll admit sounds plausible. That prompted the New Albany Ledger to print a rebuttal that was republished in in the Evansville Journal of Feb. 5, along with a sample of the offending language the Courier had printed.

According to the Courier, the Missouri had been “trying her speed” against other boats and Captain Hurd had vowed to beat them to Louisville. While at the Evansville wharf the Missouri’s boilers reportedly were “red hot” and “the boat absolutely trembled from stem to stern with the terrible power concealed in her boilers.”

Three of the Missouri’s engineers – Lawrence Schroeder, James Cox and Jim Phillips -- were from New Albany and the Ledger there was quick to rise to their defense, particularly since Cox had died that morning. With his dying breath, the Ledger said, Cox maintained the boilers “were in the most complete repair” and that “in view of the death he knew soon awaited him, that the boat was not and had not been on a race with the Dictator or any other boat.”

All three men had sterling reputations, the Ledger said. “The statement that the boilers were red hot is absolutely false.”

The Journal of Feb. 7 contained a tongue-in-cheek follow-up to that controversy. The clerk of the Dictator had earlier telegraphed a death threat to the editor of the Evansville Courier warning of dire consequences “if certain statements relative to the Dictator, published in the Courier, were not taken back.”

There was no retraction “and similar threats were hurled back.”

When the Dictator returned to Evansville, the captain went to the Courier office to try to smooth the waters, so to speak. But he was not allowed in the building until the editor had been warned.

The captain quietly entered and the editor drew his weapon “but horror! – what a terrible result. Instead of shooting the captain the untutored pistol, perhaps like its owner, went off half-cocked … doing no other damage than to shoot a few holes through an ‘innocent’ pair of pantaloons.”

The captain kept his cool, saying he had come on an errand of peace. “An armistice was at once announced and hostilities ceased.”

Throughout the spring and early summer of 1866, the Journal ran pleas from family members searching for remains of their loved ones and notices of coroner’s inquests. The last article about a Missouri victim being pulled from the river appeared in the June 4 edition. The body was so decomposed that identification was impossible.

The Journal of May 29 noted the river was down and the Missouri’s engines could soon be recovered. “We hope they will be taken out and the wreck broken up and removed, as it is a melancholy memento of a most terrible catastrophe.”

The Aug. 18 edition reported that the N.W. Casey had arrived with a barge and a boat equipped with a diving bell.

The Aug. 23 edition said the salvagers had begun work “but are making rather slow progress.”

The Aug. 25 edition said, “Portions of the Missouri’s boilers have been recovered and landed on the wharf here. They show very clearly the terrible nature of the explosion” in that the rivets in the boilers did not fail but rather “the sheets of iron were torn into shreds like a sheet of paper.”

That iron was three-eighths of an inch thick.

E.L. Starling in his History of Henderson County gives only a brief – and partially erroneous – account of the Missouri disaster but adds this telling detail: “A large sheet of one of the boilers was blown several hundred yards into the woods on the Henderson County side.”

The Journal of Nov. 26 noted the boat with the diving bell had left the wreck site the previous day. The remainder of the wreck was not removed until the fall of 1873, according to the website of the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The last information I could find in the Journal about the Missouri disaster was a brief item Dec. 18 about another type of bell: “The new bell purchased for the new (fire) engine house has been hung and it is a very fine one. It is the bell of the ill-fated Missouri and possesses a very pleasing tone.”

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Local history: The bell tolled in 1866 for the Tri-State’s worst steamboat disaster