Local history: Little mysteries from the Soap Box Derby

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Who doesn’t love a little mystery? As the All-American Soap Box Derby rolls into Akron for the 85th championship July 16-22, we’ve decided to add intrigue.

With the aid of derby historian Jeff Iula, we’ve gathered some mysterious and unusual events in the long history of the downhill race. Maybe you can help crack these cases.

A disguise among guys

Who is that little girl in the photo?

More than 325 boys entered the first Soap Box Derby on Aug. 19, 1933, in Dayton. Photographer Myron E. Scott organized the competition after seeing kids race in homemade cars on a street.

Nearly 40,000 people attended the inaugural event as ramshackle vehicles coasted down a hill. Steering a yellow racer, Randall Custer, 16, captured first place and won a motor scooter.

Scott didn’t recognize the third-place finisher.

“What’s your name, son?” he asked.

Alice Johnson, 12, the only girl in the contest, took off her hat.

“She had her long hair tucked into a cap and nobody suspected he was a she until Alice took off that cap when she came up to claim her prize,” Scott recalled years later.

Alice won a boy’s bicycle. Randall gave her a bouquet that had been presented to him. In a group photo of prize winners, Alice gazes down instead of looking at the camera.

She had built her car with her father, Edward “Al” Johnson, an aviator famous for selecting the site for Dayton International Airport. She went on to compete in the 1934 race, finishing third again.

In 1935, the All-American Soap Box Derby moved to Akron. Despite Alice’s early achievements, girls weren’t officially allowed to race until 1971.

Alice grew up, graduated from Wittenberg and served as a lieutenant junior grade in the WAVES during World War II. In 1947, she married Paul Cochrane, a former naval officer, and they settled in California.

She lived long enough to see Karren Stead, 11, become the first girl to win the All-American in 1975.

Alice Cochran died in 1985 at age 64. She is buried next to her husband at Mount Tamalpais Cemetery in San Rafael, California.

We know so little about that daring girl from 1933. What is her story?

Hat’s off to ‘Bonanza’

What happened to Hoss’ hat?

The cast of NBC-TV’s “Bonanza” made two famous appearances at the derby in the 1960s. Akron crowds were thrilled to see the cowboy actors in their Ponderosa attire at public events.

Lorne Greene (“Ben Cartwright”), Michael Landon (“Little Joe”) and Dan Blocker (“Hoss”) had such a great time in 1962 that they returned in 1964 with co-star Pernell Roberts (“Adam”), who opted to wear street clothes.

The Oil Can Derby, a celebrity race, was delayed in 1964 while handlers removed a steering wheel from a car so Blocker could fit his 285-pound frame in a seat. Blocker coasted to victory over Landon and Roberts.

During a celebration with fans, Blocker lost his cowboy hat in the crowd. Someone may have grabbed it as a souvenir. The actor left town hoping that his Hoss headgear would be returned, but he never saw it again and had to use a substitute at the Ponderosa.

Do you know where to find the hat? Maybe it’s gathering dust in an Akron closet.

Race too close to call

Who won the All-American derby in 1938? It was too close to call until someone called it.

More than 100,000 people watched the exciting finale as three cars raced down the Akron track Aug. 14:

Lane 1: Richard Ballard, 12, of White Plains, New York.

Lane 2: Stanford Hartshorn Jr., 10, of Gardner, Massachusetts.

Lane 3: Robert Berger, 14, of Omaha, Nebraska.

Stanford fell behind, but Richard and Robert were neck and neck as they neared the finish line. It was so close that spectators couldn’t tell who won. Trackside cameras offered conflicting views.

The crowd roared when an announcer hailed Richard as the winner. Derby volunteers lifted the boy in his car and brought him back to the finish line to be interviewed. For 4½ minutes, the New Yorker was champion. He even began to give a thank-you speech.

And then a voice interrupted over the loudspeaker: “There has been a mistake — correction please! The winner is Robert Berger of Omaha.”

After developing film from an overhead camera, race judges announced that the Nebraska boy was the true victor. The announcer had called the wrong car. Awkward.

Reporters and photographers abandoned Richard in mid-speech and raced to interview Robert.

The champion received a four-year scholarship.

The consolation prize wasn’t too shabby, though. Richard won a Chevrolet automobile.

To avoid future controversy, derby officials installed improved photo-finish equipment before the next race.

Pranksters in the parade

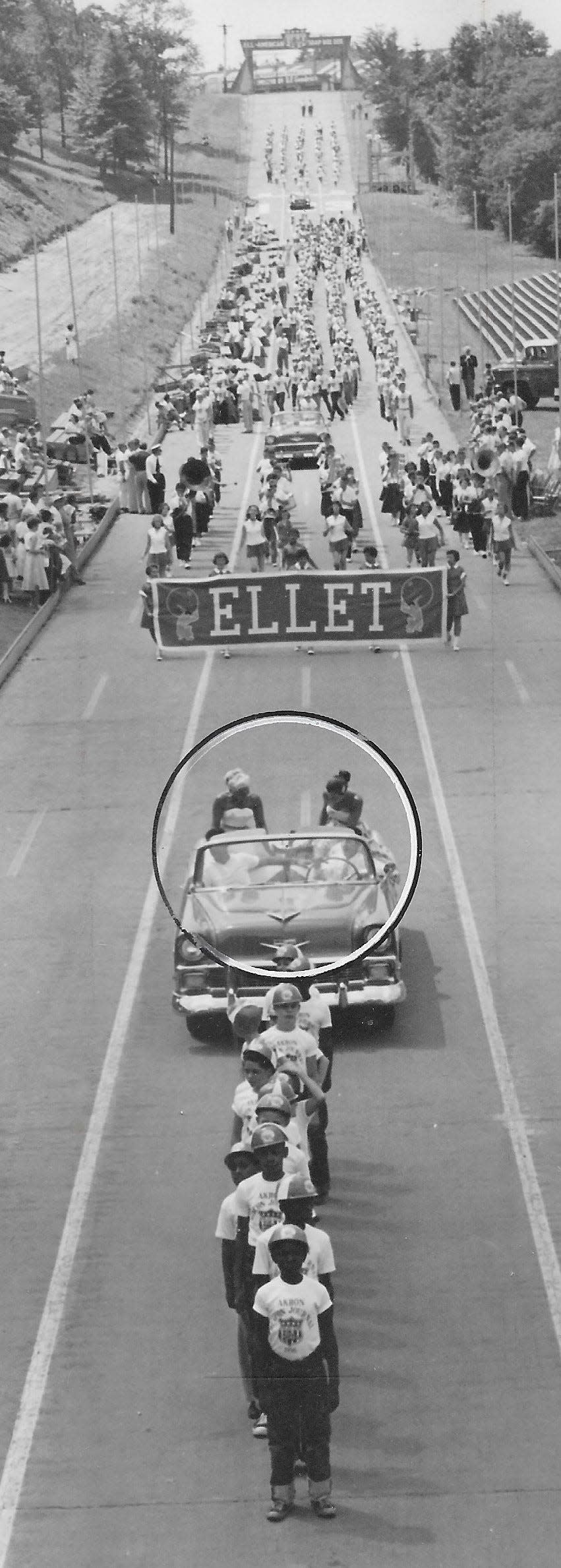

Who were the two young women riding in a convertible during the Akron parade in 1956?

They apparently were party crashers.

A blonde and a brunette, both wearing evening gowns, smiled and waved to spectators from the back seat of a Chevrolet at Derby Downs on July 25.

Announcer Jack Fitzgibbons couldn’t find them on the roster as he introduced VIPs over the public address system. Nobody in the booth knew who they were. They appeared on television unidentified.

Ralph Iula, executive director of the derby, didn’t recognize the women. He thought parade marshal Bain E. “Shorty” Fulton had invited them until Fulton asked: “Hey, Ralph, who were those girls in the convertible?”

The car had been reserved for Claude Smith, the 1941 champion from Akron, but he sat next to the driver while the women rode behind him. Smith assumed they were pageant queens.

“The parade started and they came running up to the car and jumped in,” Smith later explained. “I figured they belonged there. After all, they were prettier than me — so I sat up front.”

The two pranksters, if that’s what they were, vanished in the crowd as the parade broke up.

Calling all cars

Where did those two championship cars go?

We still don’t know whether they were stolen, lost or misplaced, but they disappeared in the 1960s after going on display at the Mayflower Hotel in downtown Akron. Coincidentally, both were from Indiana.

Freddy Mohler of Muncie built the 1953 winner, a red car painted No. 99 and emblazoned with “The Muncie Star.” David Mann of Valparaiso built the 1962 winner, a black car painted No. 66 and marked “Gary Post-Tribune” and “Gary Indiana.”

Is it a clue that 66 and 99 are similar numbers? Maybe the cars got shipped to the wrong places because someone read the figures upside-down.

Mohler, who attended the derby every year, admitted decades later that the car’s loss was a major disappointment.

“I was hurt when I got to Akron and my car wasn’t here,” he said.

In the 1990s, derby backers built exact replicas of Mohler and Mann’s cars, using the same style of vintage parts that were found in the originals.

The search continues for the real racers.

Paint it black

Did black cars run faster than light-colored ones?

Springfield Township native Fred Derks, who won the All-American in 1949, insisted that his choice of paint color was a factor in his victory because black absorbs heat.

“Out there on the hill, my black racer becomes hotter than the racers of any other color because it soaks up the heat from the sun and doesn’t throw any of it back,” he explained a year later.

“So when I drive my black car down the hill, it heats the air around it. Hot air is lighter than cold air. The light hot air around my car becomes more fluid than the air around the other cars. It eliminates drag. That is why I win.”

It was true that a higher percentage of black cars had won the All-American in Akron. Of the victors since 1935, seven rode black cars. The other four were silver, yellow, blue and red.

Derby engineering expert Walter Mackenzie threw water on the theory, insisting that “if two cars could be built exactly alike, one painted black and one white, and drive over the same measured course under identical conditions, there would not be a fraction of a second difference in their running time.”

The paint-it-black debate continued for a decade without a consensus among scientific minds. Anyone care to prove or disprove it?

Holy heartbreak, Batman

Who was that unmasked man?

Adam West, the star of ABC-TV’s “Batman,” made a rather low-key appearance at the 1967 derby. Many kids were disappointed when the Caped Crusader didn’t wear his crime-fighting costume as expected.

They didn’t recognize him.

West explained that he had injured his leg while riding a Bat surfboard in California and decided not to wear the famous outfit because he couldn’t put on his Bat boots. Honestly, that was his explanation.

Maybe the thought of wearing a hot mask in summer played a role, too.

At any rate, West competed against actors Robert Lansing and Christopher George in the Oil Can Derby.

“This is going to be a real Batman cliffhanger,” West said.

After cruising to victory, he joked: “I’m going to purchase this car. It’s faster than the Batmobile.”

Children weren’t buying it.

“My 2-year-old is broken-hearted because Adam West didn’t appear in the derby parade wearing his Batman suit,” Joyce Rhodes wrote to the Beacon Journal. “It seems West doesn’t realize the age range of his fans. Most parents and children expected to see Batman, not West.”

It’s a mystery why Batman selected Akron as the place to reveal his secret identity.

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com

Local history: Singer Pat Boone recalls 1958 visit to Akron for Soap Box Derby: ‘I’ll never forget that’

Geauga Lake revisited: Vintage photos of lost amusement park

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Local history: Little mysteries from the Soap Box Derby