Local history: Old age pension was glimmer of hope in 1934

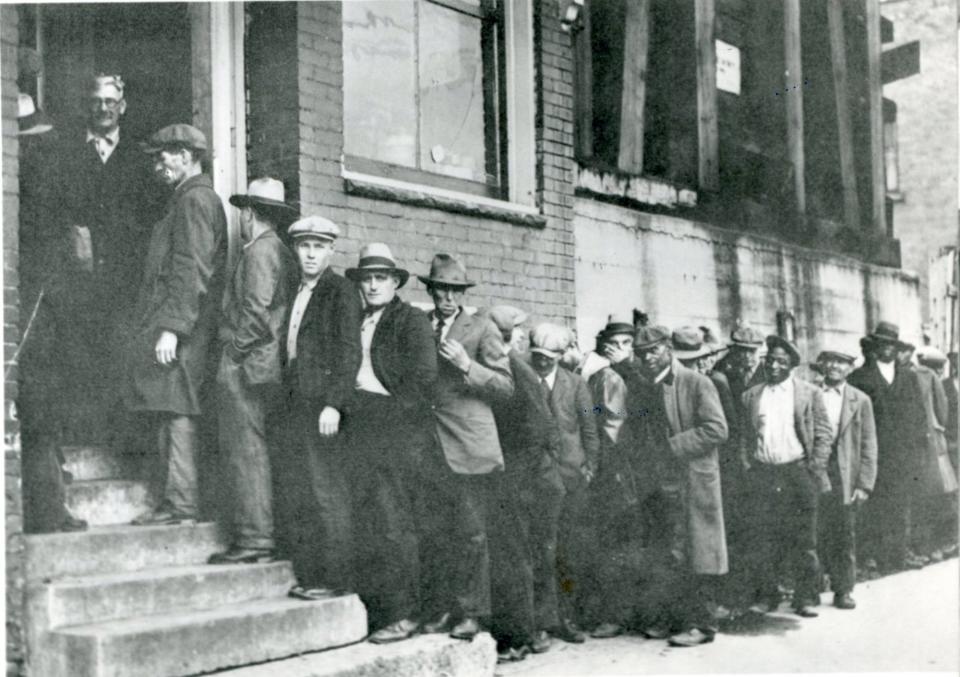

More than an hour before the office opened, they began to line up.

Some clutched canes, stooped by age and infirmities. Many couldn’t see or hear as well as their younger selves. They wore the finest clothes they could muster, suits and vests and dresses and hats, although some of the attire was noticeably threadbare.

Local history: Japanese student was trailblazer at Akron college in 1905

Buoyed by a glimmer of hope, they waited patiently. Maybe they wouldn’t have to go “over the hill to the poorhouse.”

Throngs of elderly people crowded the Summit County Relief Office on June 18, 1934, to apply for old age pensions. It was the first day that the state’s official forms were available in the downtown Akron office at 76 S. High St.

The crowd was so large that workers threw open the doors 15 minutes before the 8:30 a.m. opening. More than 11,000 people filed through the hot office on the first day.

“Men and women, some of them feeble of foot, some whose eyesight has been dimmed with years and some whose hearing is very weak, crowded a back room in the old Ohio Bell Telephone Co. early Monday morning,” Beacon Journal reporter Dorothy Doran wrote.

“They came there to file applications for old age pensions, their last ray of hope to fight a fate that has left them distressed in their advancing years. A gleam of hope shone in the eyes of the applicants despite their weary faces and their tired limbs.”

Old age and low income were a bad combination during the Great Depression. There was no safety net.

People lined up for soup, bread and jobs. Akron’s unemployment rate was roughly 60% in 1932 — or about 2 out of every 3 men.

Workers who had toiled their entire lives lost their savings and homes. People unable to support themselves feared living their final years at the county home in Munroe Falls.

Eagles propose old age pension

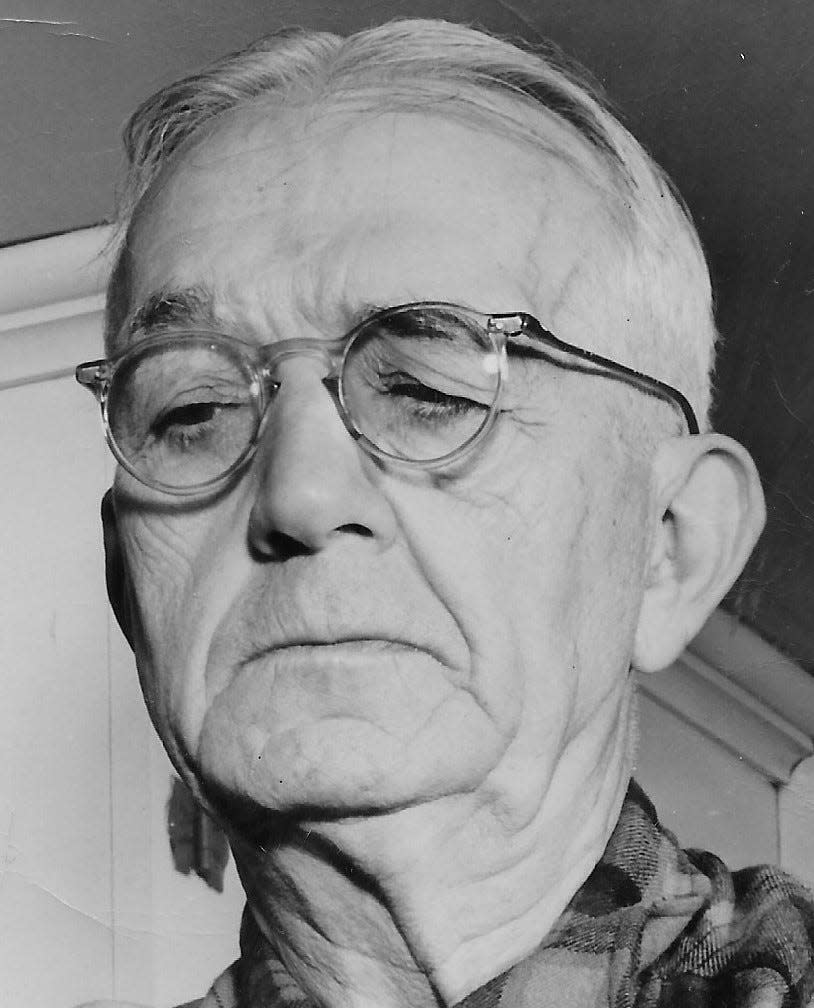

Akron resident Henry J. Berrodin wanted to make a difference. Under his leadership, the Akron chapter of the Fraternal Order of Eagles had distributed more than 300,000 meals to hungry people over a three-year span.

“The thing that gives the Eagles their greatest satisfaction is that they have been instrumental in adding to the sum total of human happiness,” Berrodin said.

After the Eagles elected him national president in 1932, he used the clout of his 600,000-member group to promote change. He turned his attention to old age pensions, which the Eagles had advocated since 1921.

“Not a state in the union at that time had old age pensions,” Berrodin said in a 1932 speech. “Today there are such laws in 17 states. Pens used by governors of those states in signing bills legalizing old age pensions are in the archives of the Eagles.”

Ohio was slow to act. A pension bill stalled in the legislature after opponents complained that the system would raise taxes. So Berrodin’s group went directly to the people.

The Eagles circulated petitions to get a state referendum on the ballot in November 1933. The issue proposed providing up to $25 a month — more than $500 today — to older Ohioans whose income did not exceed $300 a year (over $6,000 today).

To be eligible, recipients had to be 65 or older and U.S. citizens for at least 15 years.

It wasn’t close. State voters approved the issue 1.38 million to 526,211.

Ohio became the 26th state to adopt such a pension. Gov. George White signed the bill into law and presented the pen to Berrodin for preservation in the Eagles’ archives.

“The battle for old age pensions is not over,” Berrodin said. “Our fight now is to see that the necessary funds are appropriated. To stop fighting now will be giving the worthy aged a stone instead of bread.”

The legislature allocated $3 million from the state general fund to implement the program. County relief agencies added a division of aid for the aged.

Heloise Hendershot, secretary of the Summit County chapter of the American Red Cross, was named secretary of the local pension board.

“Our office is opening and the investigators will start work Monday,” Hendershot announced June 12, 1934. “The applications are lengthy and we don’t know yet just how much time will be required for the routine of making the necessary checkups.”

It was like playing a lottery. In 1934, Summit County had 11,627 people entitled to old age pensions, but there was only enough state funding for about 2,900 residents.

Busy scene at county office

First in line at 7 a.m. was Charles Burris, 73, who had walked 7 miles from the county home to apply. Hundreds arrived behind him. The crowd overwhelmed the bureau.

“The men and women in that perspiring mass in the little office were feeble, many were crippled, and all were uncomfortable, but all were good natured,” Akron Times-Press reporter Ruth Putnam wrote. “Each hoped she or he would be one of the lucky one-fourth likely to receive a pension under the new law.”

Milton G. Geissinger, 79, and his wife, Marie, 75, arrived at the office with their 73-year-old tenant Franklin M. Lacy. Geissinger had painted houses for more than 40 years but he figured he was too old to climb scaffolds.

“I’ve made a lot of folks’ houses look pretty in my day,” he said.

Retired carpenter Ransford Howland, 75, told a reporter that he hadn’t had steady work in years because of the Depression. He had earned a little money mowing grass.

“They had to go and have a drought and not need me for that,” he said.

He didn’t want to be a burden on his three adult children.

“I’ve run up a big grocery bill on my children already,” Howland said. “I want to feel like I’m paying my own way.”

Retired carpenter Jacob Yahres, 86, of Lakemore, a father of eight, remained philosophical about the tough times.

“If I ain’t got any money, I ain’t got any and that’s that,” he said. “I’ve lived as long as I have because I never worried about it.”

Zephaniah Caudill, 78, said his rheumatism was acting up and wondered if he could move up in line.

“But you wouldn’t want me to take you ahead of these good-looking ladies, would you?” secretary Hendershot said as she helped some elderly women.

“No, indeed,” Caudill said.

“God bless you,” one woman said. “I hope you’ll get it.”

The office ran out of applications by Wednesday and had to order more.

Board investigators Norma Dunn and William J. McClelland reviewed the forms. Within a month, the board had approved 50 applications out of more than 3,000 received.

Pension checks arrive in Akron

The first checks arrived Aug. 6 to six people in Summit County.

Allie Zimmerman, 68, who had provided home care to nursing patients over the past 40 years, was among the recipients. She received a $15 check.

“I am so tickled I don’t know what to think,” she told a reporter. “I think I can rent a room very reasonably in a home and I’m going to try to get by without any help.”

Joe Battin, 80, a former major-leaguer for the Philadelphia Athletics and St. Louis Brown Stockings, also got a $15 check. He lived in the basement of an Akron apartment house.

Asked what he would do with the cash, he joked: “All that money? I think I’ll found a hospital.”

Elmore Koplin, 81, who had repaired shoes for a living until he could no longer find work, received a $10 check and planned to buy new shoes. The other recipients of the first checks were William Henry Ward, $12, Bessie Danzig, $10, and Elma Wheeler, $5.

By late September, 95,000 of 120,000 eligible Ohioans had applied. Of that number, 9,600 won approval. In Summit, that amounted to 157 pensions for 534 approved applicants.

Thousands were rejected because they didn’t meet the criteria. Hundreds more died after filing the forms.

Within six months, 36,000 indigent older Ohioans had received checks. Anything was better than nothing, but it was clear that state funding was insufficient.

Social Security becomes law

U.S. lawmakers took up the gauntlet.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act on Aug. 14, 1935, as part of the New Deal program. Funded through a payroll tax, it created old age pensions, unemployment compensation, child welfare and public health programs.

“We can never insure 100% of the population against 100% of the hazards and vicissitudes of life,” Roosevelt said. “But we have tried to frame a law which will give some measure of protection to the average citizen and to his family against the loss of a job and against poverty-stricken old age.”

Today, 65 million Americans per month receive a Social Security benefit. That’s more than $1 trillion a year.

Nearly 9 out of 10 Americans 65 or older receive Social Security. According to federal estimates, the number of older Americans will grow from about 57 million in 2021 to 76 million by 2035.

One thing has remained constant since the Great Depression. Nobody wants to go “over the hill to the poorhouse.”

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com.

1972: The year that rocked the Rubber Bowl

Geauga Lake revisited: Vintage photos of lost amusement park

Remember Akron television? Memorable personalities from WAKR-TV, WAKC-TV

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: Old age pension was glimmer of hope in 1934