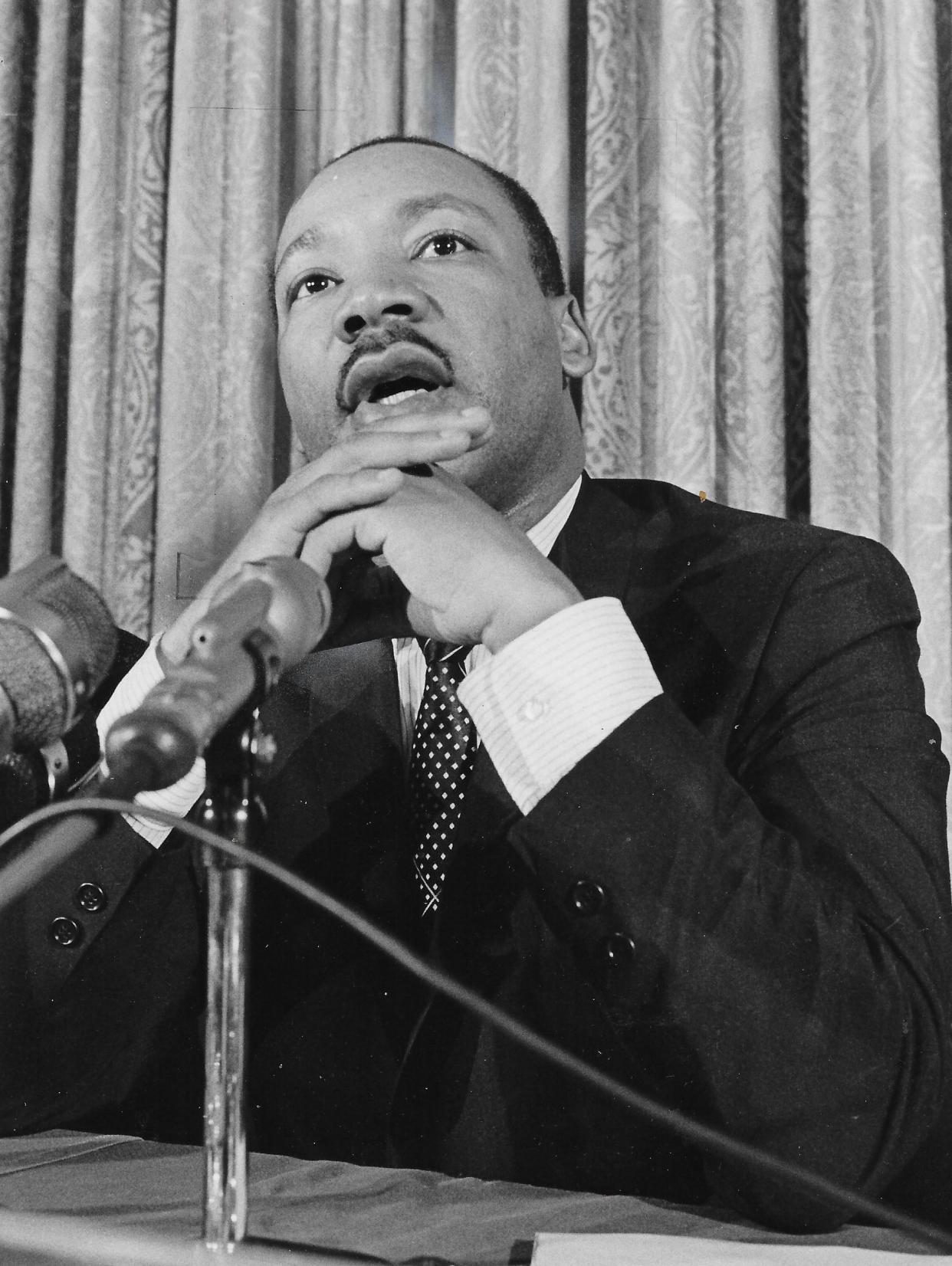

Local history: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was guest at Boston Heights hotel

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Boston Heights played an unexpected role in civil rights history.

The predominantly white village in northern Summit County served as the unlikely backdrop as the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., 38, held a series of private meetings over three days in 1967 to address ongoing concerns in Cleveland.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference reserved several rooms for King and other officials at the Yankee Clipper Inn, a seven-story hotel on Route 8 at Hines Hill Road north of the Ohio Turnpike.

The secretive proceedings, which included conversations with NAACP, Urban League and other leaders from Cleveland, addressed such topics as improving employment, housing and other opportunities for minorities.

Cleveland Mayor Ralph S. Locher, a Democrat, refused to meet with King, labeling the Nobel Prize winner “an extremist.”

Among the participants at the Boston Heights sessions June 7-9 were future U.S. congressman, U.N. ambassador and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young, executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference; the Rev. E. Randel T. Osburn, chief strategist of the SCLC; the Rev. Albert R. Sampson, project director for the group; the Rev. Walter Grevatt Jr., director of Housing Our People Economically (HOPE Inc.); and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, national coordinator of Operation Breadbasket.

Reporters looking for clues about the hotel meetings noticed a chalkboard in a conference room with charts, arrows and a scrawled list:

Basic Needs:

1. Base of money raised.

2. Office set-up

3. Staff hiring

4. Community left with permanent personnel

5. Federation

The journalists didn’t know what it meant until the final day of the meetings. King held a news conference to announce plans to improve the living conditions of Black people in Cleveland.

“We are ready to take action necessary to grapple with the problems that confront Negroes here,” he said.

King said his Cleveland goals included organizing tenant unions to bargain for better housing conditions, starting a block-by-block volunteer campaign to register voters and improving police-community relations a year after the deadly Hough riots of July 1966.

King also announced that Operation Breadbasket would expand to Cleveland. A year earlier, King had organized the program in Chicago to promote the employment of Black workers in companies.

“We feel any business ought to have a percentage of Negroes employed similar to the percentage in the population,” King told Ohio reporters. “If they don’t comply, we will urge people not to buy their products.”

With a strategy mapped out in Boston Heights, King said he would organize “a determined communitywide program of selective patronage or economic withdrawal.”

“We are not trying to put anyone out of business,” King said. “We are trying to put justice in business.”

Jackson, 25, the leader of Operation Breadbasket, further noted: “No longer will we allow the colonial powers — the white owners — to take profits and leave poverty … to take joy and leave sorrow … to take our sense of dignity and leave only despair. Ultimately, the Black ghetto must be controlled by Black people.”

King checked out of the Yankee Clipper, but returned to Cleveland a week later for the formal opening of the Operation Breadbasket headquarters on St. Clair Avenue.

On June 15, he called for the city’s bread industry to hire more Black workers or face boycotts. He said Cleveland unemployment figures showed that nearly 60% of young Black men in the city were out of jobs.

King said the city’s Black population lived behind an invisible wall “in a triple ghetto of race, poverty and human misery.”

“We will move down the line of bread companies,” King said. “We hope that all will cooperate. If some are recalcitrant, we will call on the whole community to withdraw economic support.

“We will start negotiations to get new and better jobs and increase the income and buying power for Negroes.”

The United Pastors Association pledged $150,000 to the cause. More than 200 ministers also voiced support for Operation Breadbasket.

Reporters asked bread company executives to respond to King’s efforts.

Cliff Hunt, general manager of the bakery division of Fisher Foods in Cleveland, acknowledged that the number of Black employees was “lower in the outlying bakeries,” but said: “This is not because of choice, but lack of skilled applicants.”

M.B. Beyer, president of Laub Baking Co., said “there are Negroes in all kinds of positions — sales and production. The number has never been important to me — just the qualifications.”

Robert Spieth, general manager of Ward Baking Co., noted: “There are quite a few Negroes here. There are some in the office, but that is because we have never had qualified persons to fill openings.”

Operation Breadbasket leaders reported securing agreements that led to the hiring of hundreds of Black workers in Cleveland. If companies didn’t comply, pickets went up outside stores until agreements could be reached.

With King’s support, Ohio Rep. Carl Stokes defeated Mayor Locher in the Democratic primary in October 1967 and edged Republican Seth Taft in the November general election to become the first Black mayor of a major American city.

Stokes called on Cleveland’s citizens to help him build “a great and wonderful city.”

“Never has one man owed so much to so many,” Stokes told cheering supporters. “Truly never before have I ever known, to the extent that I know tonight, the full meaning of the words: God bless America.”

The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated April 4, 1968, in Memphis, Tennessee, where he had gone to show support for striking sanitation workers. He was 39 years old.

The Yankee Clipper suffered a deadly disaster only five months after King’s stay in Boston Heights. A carbon monoxide leak Nov. 18, 1967, killed three guests, sickened more than 100 and hospitalized at least 60. Investigators traced the source to a swimming pool heater in a basement laundry room.

After the hotel shut down, the furnishings were sold at a sheriff’s sale to pay off debts. The building changed hands several times over the decades, operating as the Golden Dolphin, Brown Derby Inn, Regency Inn, Red Roof Inn, Days Inn and Hudson Inn, before finally being condemned.

The crumbling structure fell to the wrecking ball in 2004. Its role in civil rights history had long since been forgotten.

Mark J. Price can be reached at mprice@thebeaconjournal.com

Local history: Akron landmarks in Black history

Local history: 101 trailblazers who achieved famous firsts in Akron Black history

This article originally appeared on Akron Beacon Journal: The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. stayed at Boston Heights hotel in 1967