These local schools are named for people with racist histories. Is it time for a change?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Timyra Cotton of Chalmette was a freshman when, she recalls, the topic of her school’s affiliations with slavery and the Confederacy came up during conversation with friends in Nicholls State University’s cafeteria.

The students — members of the school’s NAACP chapter and of the Black Student Union — were scrolling through posts on the social media application Yik-Yak, many of which were about a pending change of street names on the Thibodaux campus. Mostly, they bore the names of local sugar plantations, a number of which were active when those who labored upon them were bound in slavery.

“A lot of students who were not students of color were saying we were making a big deal out of nothing,” Cotton recalls. “They said why should we change them now; the names have been there for so long. Some of us felt those posts showed that our feelings didn’t matter.”

Discussions continue between the Nicholls NAACP and university President Jay Clune for ways to make the campus more welcoming to all students. The proverbial elephant in the room when these talks occur is the university’s namesake, Francis Tillou Nicholls, a Confederate general from Thibodaux and governor of Louisiana, whose administration is credited with welcoming Democratic “redeemers” bent on retaining old ways in a new South, paving the way for institutionalized racial hatred and Jim Crow laws.

Nicholls is not the only local institution of learning, however, named for someone whose place on the wrong side of American history raises questions of whether their memories should continue basking in such an honor or whether a time for change has come.

Two schools and a school-related building in Terrebonne Parish and a private school in Lafourche are named for individuals with troublesome histories concerning race relations in addition to the university. Two have direct ties to the Confederacy or slavery. Two are 20th century individuals whose public statements or writings indicate tolerance if not promotion of racial segregation and bigotry.

H.L. Bourgeois: The public high school in Gray was named after Bourgeois, superintendent of Terrebonne schools for four decades, whose disdain for local Native Americans, and resulting policies, led to education being denied to them and fomented a bigoted culture.

U.S. Sen. Allen Ellender: Legendary Louisiana lawmaker who served from 1937 until his death in 1972, namesake of an east Houma high school, the library at Nicholls State University and a federal office building and post office in Houma. A staunch segregationist, Ellender, a native of Montegut, was an outspoken opponent of all civil-rights legislation and filibustered against it, voted against anti-lynching legislation and publicly referred to Black people as inferior beings.

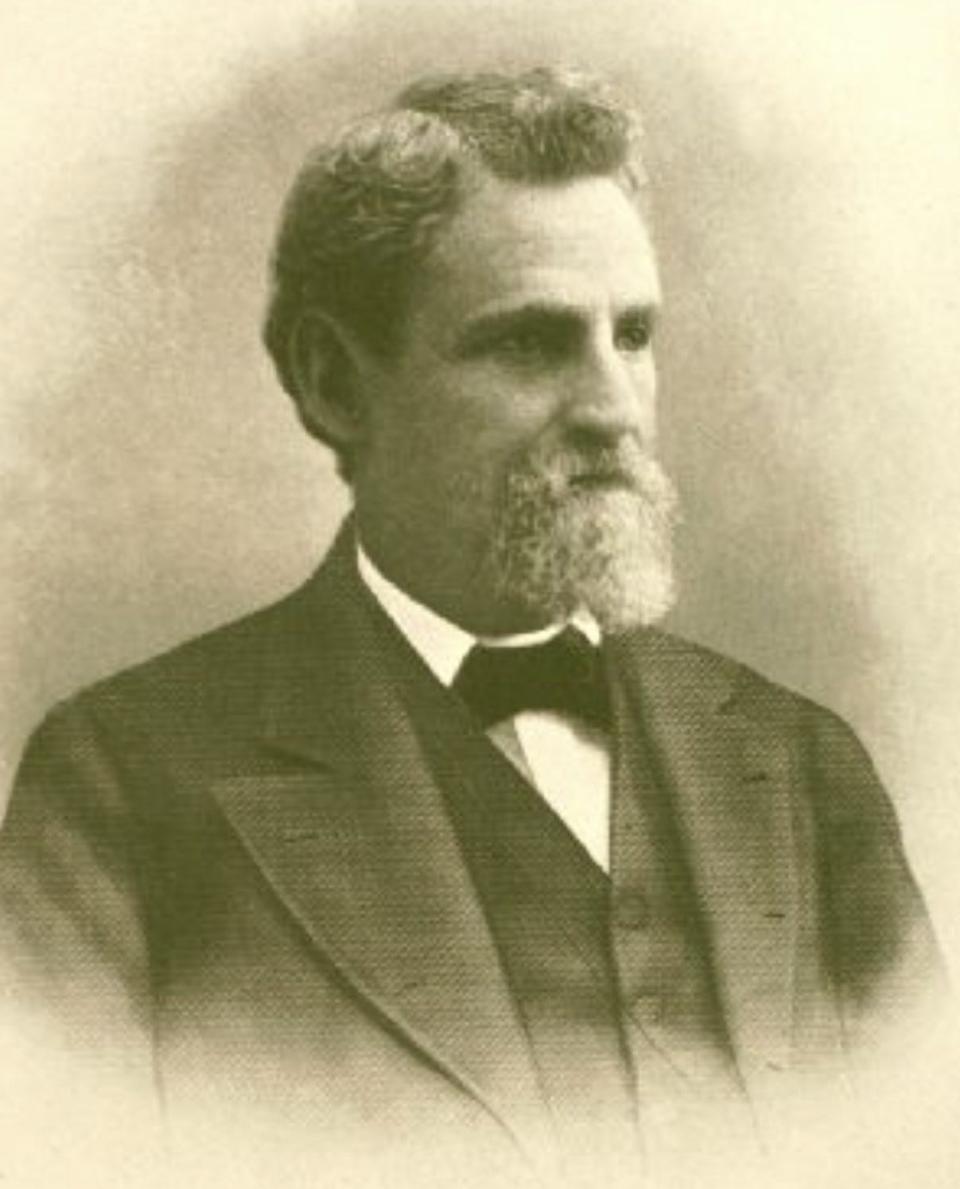

Edward Douglas White: A Thibodaux native born of a notable slave-holding family, whose father served as a Louisiana governor. White served uneventfully in a Confederate unit as a young man. As U.S. Supreme Court chief justice in 1896, White voted with the court’s majority in the Plessy vs. Ferguson case, which green-lighted “separate-but-equal” accommodations for Black people. A Catholic high school in Thibodaux bears his name. His boyhood plantation home is a state historical site.

Andrew Price: The four-term Thibodaux congressman and owner of Acadia Plantation was alleged to have taken part in the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre, which historical accounts say resulted in the deaths of anywhere from 30 to 60 Black people during a strike of sugar-cane workers. Andrew Price School in Schriever, now vacant, is his namesake, as is the separate recreation center next door.

‘No redeeming quality’

Manisha Sinha, Draper Chair in American History at the University of Connecticut, has written and lectured extensively on 21st Century American adjustments to the sins of the nation’s past, including removal of statutes and changing of street, building and school names that honor Confederate officers and others involved with the rebellion. She is particularly concerned about schools.

“Children are attending these schools, and Confederate leaders and generals had absolutely no redeeming quality to them,” Sinha said in an interview. “They promoted white supremacy in the South. They committed treason against the Republic. We should not be commemorating Confederate leaders, and we should not be commemorating segregationists.”

Unlike many cities, towns and counties across the U.S., Terrebonne and Lafourche have not experienced rancor and division over issues such as removal of statues. There are no actual monuments or statues honoring Confederates in the two parishes.

Confederate Reckoning: Across the US, universities grapple with past ties to slavery and segregation and threads of racism that remain

The names of schools in the area largely appear in a unique context, draped in confusing paradox.

Ellender — despite his white-supremacist views — is hailed as a hero by many locals for benefits to the community he arranged and supported as a senator. Bourgeois was a beloved figure for decades in Terrebonne. To residents who are not Native American, his contentious words and actions regarding that minority don’t appear to raise much in the way of red flags. E.D. White, whose racist views are well documented, also has a record that indicates more enlightened thinking in his later years.

‘The right thing to do’

The question of whose names should remain on school buildings or be honored otherwise in public spaces is a weighty one being asked more and more over the past decade throughout the country.

Locally, other than the discussions about Nicholls State, scant attention has been paid to the school-naming question. The Catholic Diocese of Houma-Thibodaux did address the question of whether E.D. White High’s name should be changed but decided against doing so.

Civil-rights advocates have not raised questions publicly, for the most part, though some acknowledge the issue has been a topic of private discussion.

“Around the country, there is a lot of talk about names, but locally a lot of times people don’t bring these things up because they think it might be too controversial,” said Terrebonne NAACP President Jerome Boykin. “But it should still be brought up. Clearly, there should be a discussion and an action taken against these schools remaining named against segregationists and people who had racist histories and intent. It is the right thing to do.”

Silence, Boykin said, should not be interpreted as acceptance.

“It has come up, but when you are fighting a lot of different issues on the forefront, sometimes other issues that are just as important don’t get discussed. Just because you haven’t said anything doesn’t make it less important.”

'Consider the context'

Other community voices, however, question the advisability of raising the issue of institutional names.

Dennis Gaubert, a retired Thibodaux attorney, former Civil War reenactor and former Sons of Confederate Veterans camp commander, doesn’t see an upside for local communities when it comes to raising the topic.

“The mere presence of a name or a statue doesn’t necessarily mean the person is being glorified,” Gaubert said. “You have to consider the context. What is in fashion now may not be in fashion 20 years from now. You can’t say this is frozen in time and that this is going to be the societal context that will forever exist. We must let each era be judged on its own merits.”

Confederate monuments: What the men honored by statues did and believed

But what are those merits?

Interviews with educators, activists, students and some elected officials over the past six months by The Houma Courier and Thibodaux Daily Comet indicate a paucity of local knowledge about people, places and events that relate to such discussions.

“I don’t know a lot,” acknowledged retired Terrebonne Parish Council member John Navy, who worked as a guidance counselor for years at Ellender High in Houma. “The students don’t know anything about the history. But I think the kids need to know the history, period. They need to know all aspects of the past so they know where they will go in the future.”

Next in the series: Nicholls State University in Thibodaux. John Kelly DeSantis is a freelance journalist and a former reporter for the Houma Courier and Thibodaux Daily Comet.

This article originally appeared on The Courier: Do you know the racist histories of these local schools' namesakes?