The New Loch Ness Monster Photo May Be a Fake—but the Mystery Endures

Is the new picture of the Loch Ness Monster really of the Loch Ness Monster, or of a large fish? Is it not a creature at all? Is the photograph real or a fake, as experts speaking to The Daily Beast—and as Twitter—think? Is it doctored or Photoshopped?

The kinds of questions about Steve Challice’s image of whatever-the-hell-it-is taken last September in the infamous Scottish body of water, and only now revealed to a world in urgent need of some Nessie excitement, have been asked of every photograph or video of the Loch Ness Monster since the first alleged photograph of the monster was taken in 1933 by Hugh Gray, which seems to show an eel-like shape making a thrashing mini-wall of water.

Loch Ness Monster’s Existence Could Be Proven With eDNA

The following year came the iconic “Surgeon’s photograph” of Nessie’s neck apparently protruding from the water, like a periscope, leading to the belief that the loch contained at least one plesiosaur, or family of plesiosaurs regenerating in the loch’s murky depths through time. Nessie’s period of enduring global fame is approaching its centenary.

Both those images have been marked as fakes as the years have gone on. But the Loch Ness Monster mystery is eternal, stretching back to its first alleged sighting by St. Columba in A.D. 565. Its believers do not believe faked pictures disprove their idol’s existence and point to less-contested images like Tim Dinsdale’s film of 1960, and evocative stories such as that of George Spicer and his wife.

In 1933 the Spicers allegedly came across the monster—which they called “a most extraordinary form of animal”—while driving their car beside the loch. The creature reportedly lurched across the road, burrowed through undergrowth, and then submerged itself back into Loch Ness’ welcomingly murky depths. A year later, a motorcyclist claimed to have almost hit Nessie crossing the road late one night.

Along with Bigfoot, Nessie relies on the oxygen of mystery. While a growing paucity of pictures suggests the monster has become shyer as the years have gone on (or died), in 2016 it was reported to have possibly moved to London.

A view of the Loch Ness Monster, near Inverness, Scotland, April 19, 1934. The photograph, one of two pictures known as the 'surgeon's photographs,' was allegedly taken by Colonel Robert Kenneth Wilson, though it was later exposed as a hoax by one of the participants, Chris Spurling, who, on his deathbed, revealed that the pictures were staged by himself, Marmaduke and Ian Wetherell, and Wilson.

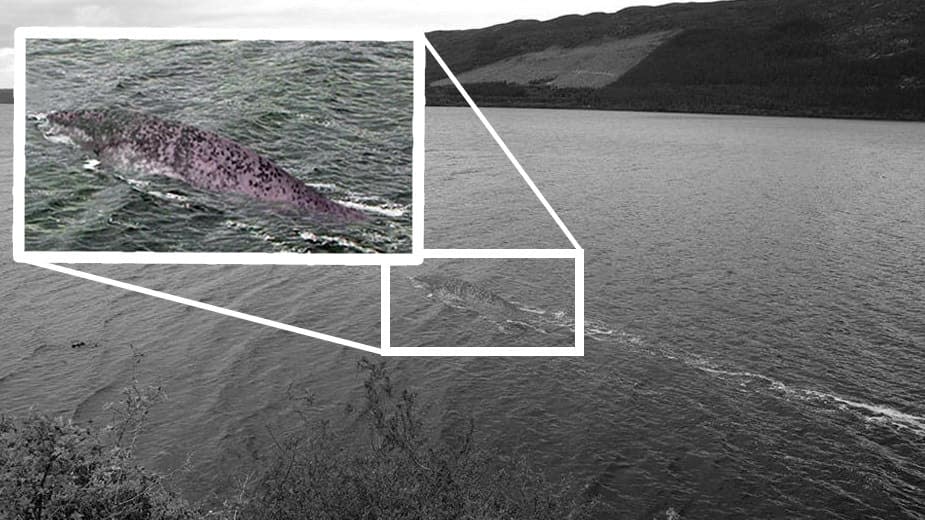

Challice, from Southampton, England, said he photographed this creature from the shore at Urquhart Castle. For any Nessie fan, this is catnip, raising the memory of Peter MacNab’s famous 1955 image of a black-humped mass in the waters forming a wake near the castle itself. (Yes, there is debate about whether this image is faked too.)

Challice’s shot shows what he was assumed was a big fish, about 8 feet long. It looks pink and speckled, like a ginormous salmon, and behind it is a foaming trail.

Challice told the Daily Record that he thought this creature was a catfish—a long-standing suggestion is that Victorians may have introduced this breed into the Loch.

“In my opinion (and I’m no expert) I think it’s a large fish that got into the Loch from the sea,” he told the paper. “As to what it is personally, I think it’s a cat fish or something like that but a big one. Someone suggested it may be sturgeon. It’s very large as the bit you can see must be at least 8-foot-long and who can tell what amount is below the surface. The water is very dark in Loch Ness so it’s hard to tell.”

On how the photo came to be, Challice went on: “I saw a disturbance in the water in front of me and took an image, then a second one, and suddenly this fish came out of the water and I got an image of it. It was gone almost instantly, so much so I wasn’t sure if I had got it or not. I guess it was something of a fluke shot. I waited about for a bit and took another image but didn’t see the fish again.”

Challice said that while the photographs were taken nearly a year ago, it was only now, during lockdown, he had had time to go through them.

Adrian Shine, naturalist and longtime leader of the Loch Ness Project, which studies Loch Ness, dismissed the new photograph as a likely fake.

“It tells us that the person is not bad with Photoshop,” Shine told The Daily Beast. “This photograph looks like it has been doctored. The person says they were 30 feet away from the Loch. This was taken from more than 30 feet away. There are trees in the foreground.”

“New photo looks like a fake to me. Looks Photoshopped,” Professor Neil Gemmell of the University of Otago in New Zealand told The Daily Beast. Professor Gemmell, with others like Shine and the Rivers and Lochs Institute at Inverness College UHI, conducted a mass-DNA sampling of the loch last year. The headline conclusion of this “very elegant study,” as Shine called it, was that the Loch Ness Monster might be a giant eel.

Shine was adamant that the foaming trail in the Challice photograph was not a wake from a creature but “Langmuir circulations,” cells of rotating water, formed by wind. It could also possibly be the propeller wash from a boat, which has been removed from the photograph and replaced by the mysterious hump. “It is not a wake,” Shine said sternly. “A wake is a series of waves which radiate out from a vessel.”

The image itself is certainly different from any other produced, said Shine. “Almost all the images produced are actually fakes,” he said. “Who knows, one day we might get a genuine one. This thing looks extremely, shall we say, fishy,” he added, laughing.

“I never did believe there were prehistoric monsters here. I am intrigued that might be a big fish, like a sturgeon”

Adrian Shine has been studying Loch Ness since 1973 and lives full-time in the loch-side village of Drumnadrochit. He describes himself as a “skeptical investigator” of whatever is in the loch, continuing the work that was begun by The Loch Ness Phenomena Investigation Bureau, founded in 1962 by figures including the famed naturalist and conservationist Sir Peter Scott.

“I didn’t enter the field as a skeptic,” said Shine. “At first I thought there was a strong human case from people’s testimonies of a phenomenon to be investigated that to all intents and purposes seemed to be an animal. Certainly the evidence seemed compelling at the time. But I have grown long in tooth in the endeavor, and you inevitably amass experience.”

For Shine, as for many other experts, Robert H. Rines’ famous “flipper” images of 1972 do not show the monster’s diamond-shaped fins, and Rines’ 1975 photographs of the monster’s alleged head and what looks like a suspended body, with cute belly, are misleading results of image enhancement.

“There is lot of fakery in the mix” when it comes to images of the monster, said Shine. “I never did believe there were prehistoric monsters here. I am intrigued that might be a big fish, like a sturgeon.”

Shine has taken part in all the major modern-era investigations at the Loch, including a decade-long special investigation, as well as a vigil involving underwater cameras and the sonar sweep Operation Deepscan in 1987. His team has collected an entire Holocene sedimentary sequence from the Loch’s bed. Shine also investigated the Loch Morar monster, with little success, but at least the water was clearer than at Loch Ness.

Most recently, last September Shine collaborated with Professor Gemmell’s DNA study, which found “a lot of eel DNA” in the loch. Shine said “lateral thinking” could extrapolate that an eel or family of eels that did not return to the Sargasso Sea stayed in the Loch “and becomes enormous.”

That idea has become known as “the eunuch eel theory,” said Shine. The eel DNA found last year only signaled the presence of eels, not their size. A giant eel’s DNA would be the same as “their more conventional brothers and sisters,” said Shine.

“There is not a lot of resident food in the loch. Virtually everything in Loch Ness has been recorded. There is nothing unusual there. It’s game over in that respect,” said Shine. “But that doesn’t mean the hunt for the Loch Ness Monster is over.”

The search, he said, now involved “human perception, human expectation, cultural tradition, and the way our minds work. I look at the loch to see many things that make up the amalgam that is the Loch Ness Monster. Do I believe in the Loch Ness Monster? Yes, of course I do, like I believe in the Fata Morgana, and the Brocken Spectre. They are all elements of illusion and human perception. When we see them we are confirming what we are supposed to see.”

Former Royal Air Force pilot Tim Dinsdale displays a model he made of the storied Loch Ness Monster in London, June 16, 1960. Dinsdale said he thought the monster could be a type of large reptile, possibly an evolved form of Plesiosaur, an aquatic dinosaur that existed more than 60 million years ago.

In blunt terms, for Shine the Loch Ness Monster may be the unexpected behavior of an animal that people at Loch Ness label its resident monster. For Shine, the Loch Ness Monster is “70 percent boat wakes, 20 percent water birds, and 10 percent everything else—logs and whatever.” (The Caledonian Canal passes through the Loch, meaning large craft traverse it.)

Shine is adamant that he does not want to rain on anyone’s monster-loving parade. As a fervent naturalist, he is as captivated today by this mysterious expanse of water as he was when he arrived in the 1970s.

He loves to talk about species diversity, plankton, fish, and sediment, or locating the wreckage on the bed of the loch last year of Crusader, the boat John Cobb used in his attempt to break the world water speed record in 1952. (Cobb died in the crash.)

“I have made a lot of general discoveries over the years, which is more than enough to keep me interested,” said Shine. Asked if he had ever seen anything he could not explain, Shine said there were things he couldn’t explain at the time that subsequent investigation later provided an explanation for.

“The mystery will be retained because there is some uncertainty around all the scientific approaches thus far used to look for evidence of a monster,” Professor Gemmell told The Daily Beast.

“There are creatures which could be seen there which might be unexpected there,” Shine said of the presence or not of something at Loch Ness. “We’ve got a seal in there who a month or two ago came in chasing salmon up river. People may see unexpected animals, but you would have to define ‘monster’ for me.”

A time-defying Plesiosaur, perhaps?

“Definitely not. The problem is they’re extinct you know,” Shine laughed. “Loch Ness is terribly cold. It’s the last place on Earth you’d expect a Jurassic reptile known to live in shallow, warm seas.”

But Nessie may be hiding, the monster’s faithful believers will think. Every time the scientists come, Nessie dives deeper and hides. She’s a diva. She’s the Garbo of the animal kingdom. She knows when to do her headline-grabbing cameos and when to disappear.

“It’s called cognitive dissonance when you get bad news about your world view,” Shine said about the continued belief in the monster. “There are two ways out of it. Denial: In the case of the Loch Ness Monster this means dismissing years of investigation, and claiming the monster is hiding in caves at the bottom of the Loch, hiding from sonar. You’d say that the 20 percent of DNA found in Loch Ness as unreadable meant something, or that the research was faulty.”

Yes to all of that, Nessie fans would say.

“That’s denial,” said Shine, brusquely.

He has his own theory of “cognitive revision,” which allows that people still want to believe in monsters, but modifies what “monsters” might mean. This would mean accepting people were seeing individual animals, not a resident monster. It might mean accepting the monster is a big fish.

“This would have been unthinkable to the credulous hippies of the 1960s,” said Shine. “That would not have been an acceptable monster. Now it’s OK to think it might be an eel.”

“A sturgeon is a very acceptable monster to me,” said Shine, sounding very Dowager Countess of Grantham. “Or there’s the big eel idea. Or a cat fish, which is what the man who took this photograph said. Why did he think that? Because it’s doing the rounds.”

Shine paused. “It’s all quite complicated. You could have a monster fish, a monster mammal—some people have suggested it could be long-legged seals. The only credible theories left are fish-y ones, and is an unexpected big fish going to qualify as a monster?”

There was still “plenty to discover” in Loch Ness, Professor Gemmell told The Daily Beast, “albeit not anything overly large and glamorous—small nematode worms, bacteria, and other life that is nestled in the depths of the Loch. We are hopeful to get those findings out soon.”

For Shine, “the monster” is probably boat wakes. But he will continue his work there for the rest of his life. “I’ve been captured by Loch Ness,” he said.

His successors “will discover more things. This won’t be the last theory about what the Loch Ness Monster might be.”

The battle to accept the Loch Ness Monster for what it is—and isn’t—lies within ourselves, Shine told The Daily Beast.

“Ultimately, when we recognize the combination of cultural stereotypes and expectations that are confirmed by physical phenomena on the Loch, then we will indeed have a ‘Loch Ness Monster’ as a phenomenon, if not an animal,” he said.

Well, at least the new picture, fake or not, has cheered everyone up a bit in this tense, dour time, this reporter said.

“Yes, it has added to the gaiety of nations,” said Adrian Shine. “And long may it go on.”

Get our top stories in your inbox every day. Sign up now!

Daily Beast Membership: Beast Inside goes deeper on the stories that matter to you. Learn more.