In a long line of medical conspiracy theories, ivermectin is the latest to seduce many, including Aaron Rodgers

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This story was republished on Jan. 14, 2022 to make it free for all readers

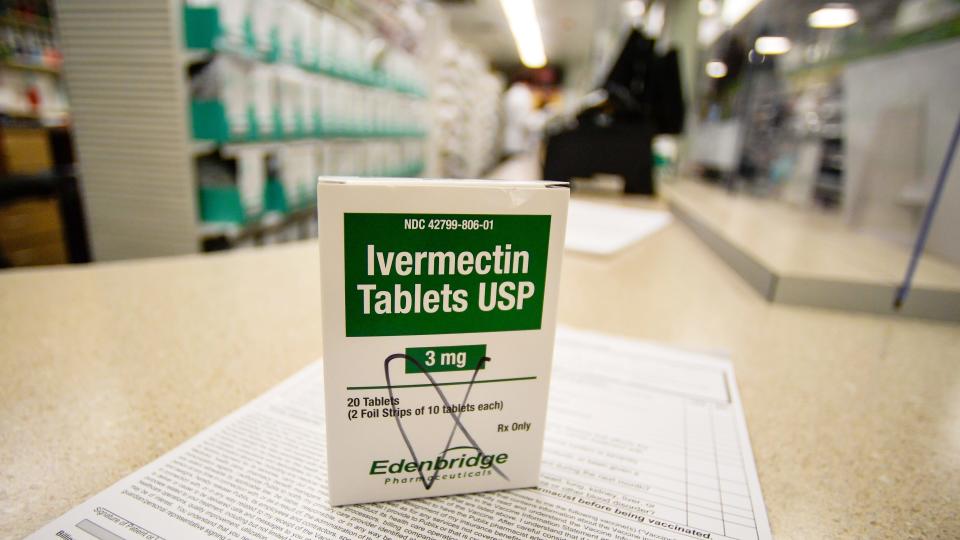

For nearly all of last year, the anti-parasite drug ivermectin remained largely outside the mainstream of American medicine as a potential COVID-19 treatment.

But beginning in early December, something changed. Retail prescriptions for the drug, which had remained mostly flat throughout much of the year, took off, jumping from less than 10,000 a week in November to nearly 40,000 by early January.

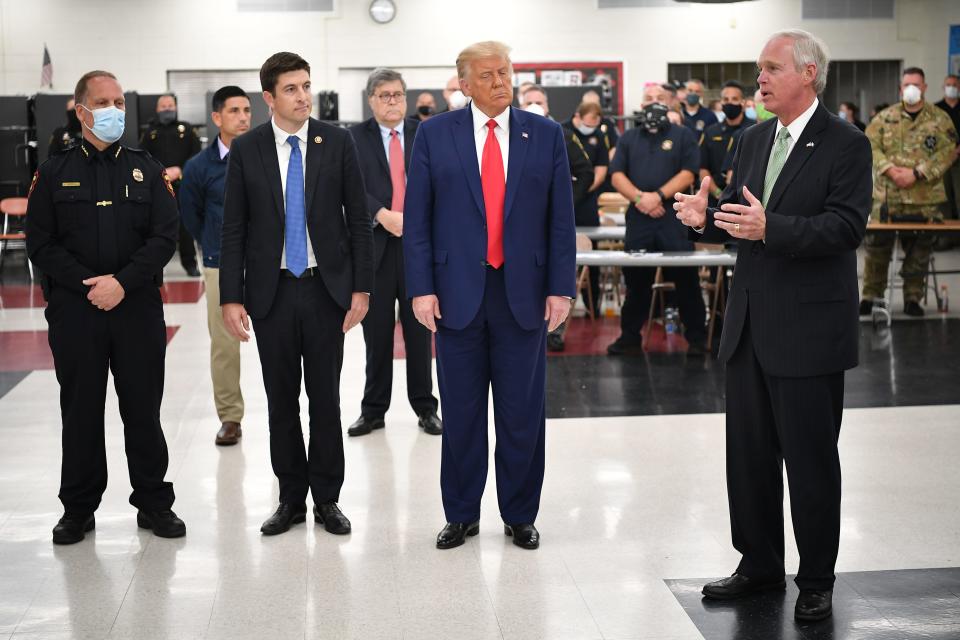

It is uncertain what prompted the surge, but on Dec. 8, U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson of Wisconsin received national attention when he held a Senate hearing in which physician witnesses touted the drug as a COVID treatment and claimed positive research about ivermectin was being ignored.

Since then, the country has been in the grips of a budding medical conspiracy theory surrounding the drug.

The theory suggests that the government and medical establishment have deliberately put their efforts behind vaccines and suppressed or distorted information about ivermectin that could have saved thousands of lives.

Pierre Kory, a Wisconsin physician and one of ivermectin's most vociferous promoters, testified at Johnson's hearing that if people took the drug they would not get sick. Eight months later, despite taking ivermectin weekly, Kory came down with COVID.

Undeterred, he has advocated for doubling the use of the drug to twice a week. A spokesperson for Kory did not respond to questions about whether he had been vaccinated prior to contracting COVID.

Also caught up in the ivermectin saga is Green Bay Packers quarterback Aaron Rodgers, who made a misleading statement about being vaccinated and then, after contracting COVID, used ivermectin as a treatment.

But recent research indicates the drug doesn’t work against COVID, and major health organizations, noting the low certainty of evidence of earlier studies, have said don’t use the drug outside of a clinical trial.

Ivermectin got a boost not only from Kory and a small contingent of like-minded doctors but also from a strong campaign on social media. The campaign has championed the drug, while simultaneously vilifying researchers who have found no evidence that it helps patients.

Ivermectin researchers have received deaths threats and hate mail; animal ivermectin supplies of the drug have flown off the shelves; and cases of human poisonings with animal and human formulations have surged.

Through Oct. 31 of this year, there have been 1,810 cases of ivermectin poisoning nationally, compared with 499 for the same period in 2019, according to the American Association of Poison Control Centers. The numbers only involve cases reported to the association's 55 poison centers across the country.

"There could be a much larger incidence than we are aware of ... that goes unreported," said association president Julie Weber, a pharmacist.

About 75% of the reported cases were considered to be of minor, minimal or no consequence.

A growing concern is that some people may not be getting vaccinated because they think a cheap, life-saving treatment is as near as their local pharmacy or veterinary source. All for a drug that remains unproven and that some recent research suggests does not work against COVID-19.

On Oct. 25, a large re-analysis by British researchers of 12 ivermectin clinical trials found that some of those trials had a high risk of bias or possible fraud. When those were excluded, ivermectin showed no significant survival benefit. That research has not yet been peer-reviewed.

The final word on the drug has yet to be written. Two large studies, one in the U.S. and one in Great Britain, are ongoing; it might be months before results are in.

Why do some people embrace the drug so strongly?

“It’s a conspiracy theory — 100%,” said Steven Novella, an associate professor of neurology at the Yale School of Medicine who also hosts the Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe, a weekly podcast that looks at pseudoscience and conspiracy theories.

“We are living in a time when basic medical decisions have been politicized,” he said.

More: Five things to know about ivermectin, one of the drugs Aaron Rodgers used for COVID-19

More: Aaron Rodgers raises concerns about COVID vaccines. Here's what health officials say.

Prescriptions soar

In humans, the FDA has approved ivermectin to treat infections caused by some parasitic worms and, topically, for head lice and the skin disorder rosacea. In animals, it is used as a deworming treatment.

In an August health advisory, the CDC said that prior to the pandemic, outpatient retail prescriptions of ivermectin averaged 3,600 a week. Though prescriptions started to creep up in the weeks just before Johnson's Dec. 8 hearing, by the week ending Dec. 11, prescriptions hit 15,000, according to data from IQVIA, which does drug market research. Scripts were at 39,000 the week ending Jan. 8.

In a statement, Johnson noted that he has held two hearings (he also held one in November 2020) to raise awareness on potential early treatment options.

"I have always been agnostic regarding which drugs might prove effective, and believe we should listen with an open mind to doctors who have had the courage and compassion to actually treat Covid patients," he said.

"If these hearings sparked interest on the part of Covid patients to ask their doctor about early treatment options, I am very happy they did," said Johnson, a Republican.

What does he think about experts who say ivermectin has become a medical conspiracy theory?

"I also believe a little more modesty on the part of ‘the experts’ making all their ‘science-based’ pronouncements might be in order,” he said.

Ivermectin also received favorable mention on the Dec. 1 Laura Ingraham Fox News show. Then, on the evening of Johnson’s Dec. 8 hearing, Ingraham brought on a doctor who promoted combinations of existing drugs, including ivermectin, that he said could cut mortality in half.

On the program, Ingraham floated a contention about why ivermectin and other existing drugs weren’t being taken more seriously by federal health officials: She questioned whether COVID vaccines could have gotten emergency-use authorization if there were existing drugs that were safe and effective against COVID.

“Ron Johnson deserves three gold stars for bringing those great experts to the field so people could actually hear them,” she said.

Echoing Ingraham’s suspicion, Johnson made a similar statement in April about possible early treatment drugs on a conservative talk radio program. “Is that what’s going on here?” he said. “I don’t know. I’m just suspicious.”

As the drug got more media attention, ivermectin prescriptions continued to surge in the months after Johnson’s hearing.

Weekly prescriptions took off again in July, jumping from 19,000 the week ending July 9 to 88,000 the week ending Aug. 13, according to IQVIA. Data since then has not been available.

'It is sinister'

Throughout this year, Johnson has brought up the drug.

In April, he mentioned it at a state Republican Party event. He said: “Ivermectin, hydroxychloroquine, just early treatment. That could have stopped the pandemic before we even had a vaccine.” He also told the audience that “health agencies” had vilified the doctors who promoted early treatments in comments before his committee.

And in June at a Milwaukee Press Club event, Johnson criticized the Trump and Biden administrations for “not only ignoring but working against robust research (on) the use of cheap, generic drugs to be repurposed for early treatment of COVID.”

It is true that it was not until April of this year that the National Institutes of Health announced a large clinical trial to look at existing drugs and over-the-counter medications that people could self-administer at home to treat COVID. The trial, which involves 15,000 people, is looking at three drugs, including ivermectin, as well as fluvoxamine, a drug used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder and depression, and fluticasone, an inhaled allergy drug.

However, early in the pandemic, NIH did sponsor a clinical trial of hydroxychloroquine in patients hospitalized with COVID, but that trial was stopped in June 2020 when it was determined that while there was no harm, the drug was unlikely to be of benefit.

It is also true that drug companies have not conducted big clinical trials of ivermectin, which, as a generic drug, doesn’t offer the kind of profit potential as new, proprietary drugs. Instead, they have focused on testing novel agents that can be priced much higher.

However, others have done important research on cheap existing drugs. Last year, a large British trial showed that the corticosteroid dexamethasone reduced mortality in hospitalized COVID patients on oxygen or ventilators. And last month, a large trial by researchers in Canada and Brazil of the generic antidepressant drug fluvoxamine found substantial reductions in hospitalization or retention in a mobile COVID hospital lasting more than six hours as well as mortality.

Last month, Johnson appeared on Fox News’ “Sunday Morning Futures,” claiming that drug companies, the FDA and health agencies were “denigrating and scaring people about ivermectin.” Then he presented some statistics on how safe ivermectin has been over the last 25 years and how many deaths have been linked to the COVID vaccines.

“So, again, there is something going on here,” he said. “I believe it is sinister. I can’t explain it. But hopefully, eventually, the truth will come out.”

Johnson also last month sent a letter to the top federal health agencies, accusing public health officials of taking part in an aggressive campaign against the use of specific early treatment options.

“Rather than seriously consider evidence showing the potential of early treatments including ivermectin, your agencies prefer to mischaracterize, conflate and misconstrue anything that goes against the mainstream narrative and the financial interests of the pharmaceutical industry,” the letter said.

The letter was signed by 21 of Johnson’s Republican colleagues in Congress, including 19 who voted against certifying the presidential election. Johnson voted to certify the election. One of the signers, Maryland Rep. Andy Harris, who voted against certifying the election, is a physician who has prescribed ivermectin, according to news accounts.

In his statement to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Johnson said he has been a leading advocate for researching existing drugs as potential COVID treatments, but he has been “agnostic regarding which drugs might prove effective."

“Had our federal health agencies devoted sufficient effort and research to help develop effective early treatment, thousands of lives could have been saved,” he said. “Unfortunately, federal health agencies and too many in the field of medicine ignored early treatment and focused almost exclusively on vaccines — which I also supported.”

'Do no harm'

Despite warnings from public health officials, ivermectin is considered an effective COVID drug by a segment of society.

“We hear stories of people saying they were on ivermectin and they were doing well, then someone pulled it, and some of them ended up on a ventilator,” said Twila Brase, president and co-founder of the Citizens’ Council for Health Freedom, a national nonprofit group that has put up billboards in Wisconsin and other states urging people “Don’t Be Bullied” into taking the vaccines against COVID-19.

“Our overall position is that patients are suffering, and they don’t have enough information to make an informed decision," Brase said. There’s information being withheld from them about adverse reactions (to the vaccines) and the early treatment options.”

But federal health agencies provide a considerable amount of data about vaccine adverse events and treatment options. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention posts information about deaths following vaccination on its website with the caveat that the numbers do not mean that the deaths were caused by vaccination. The CDC also posts information on treatments options here and here. The FDA has explained why patients should not use ivermectin.

Carl Solie, 55, said he tried ivermectin after getting COVID in early August. Solie, who was not vaccinated and lives in Elm Grove, said he did not have breathing problems or a fever, but after 12 days of feeling like he could not get out of bed, he got an ivermectin prescription.

He took his first dose around 5 p.m. on a Thursday and by Saturday afternoon he was feeling better, he said.

"It was like somebody flipped on a light switch," he said. "I had no brain fog. I got my sense of smell and taste back."

Solie said he is 90% certain it was the ivermectin and not the illness running its course that led to him getting better. "I don't see any downside to trying it," he said. "It's cheap and it works."

Such stories are not endorsed by Wisconsin doctors contacted by the Journal Sentinel who were adamant about not prescribing the drug because of a lack of data that it is of any benefit.

"I don't use it, and as far as I know, nobody in the Advocate Aurora system is using it at all," said Minhaj Husain, a doctor specializing in infectious diseases at Aurora St. Luke's Hospital. "We don't have any robust data to suggest that it's of any value in treating COVID patients."

He added: "I have an obligation to do no harm. It would not be morally or ethically right to treat a patient with a drug where there is no data that supports its usage."

Husain said some COVID-19 patients and their family members have asked for ivermectin, and "I've told them I can't do it and I won't do it. It's my job to protect patients. It's our job to educate them about the lack of evidence and the potential for harm."

He took issue with those who suggest doctors have been pushing vaccines while withholding an effective treatment.

"It's unfortunate that some patients think we have something hidden up our sleeves," Husain said. "I wish ivermectin were the cure, but that's not the case."

Nasia Safdar, medical director, infection control, UW Health in Madison, noted that the CDC, FDA and even the company that makes ivermectin do not recommend its use. "UW Health is committed to following the best available medical evidence and does not support the use of Ivermectin to treat or prevent COVID-19," she said.

Some ivermectin supporters say the drug is being dismissed because pharmaceutical companies can make more money selling other products or that it was being ignored in order to rush vaccines onto the market. The argument is that if an effective COVID treatment already existed, the need for emergency vaccines would have been reduced.

Medical conspiracies have captured the public’s attention for decades. Among the most believed, according to a 2014 paper in JAMA Internal Medicine: The FDA was deliberately preventing the public from getting natural cancer cures because of pressure from drug companies, which was believed by 37% of Americans; health officials and corporations knew cellphones caused cancer but did nothing to stop it, believed by 20%; and doctors and the government knew that vaccines caused autism and other psychological disorders but continued to vaccinate children, believed by 20%.

When people embrace unproven treatments it is a form of magical thinking, said J. Eric Oliver, lead author of the JAMA paper and a professor of political science at the University of Chicago. “It’s a whole world view that is distrusting of science and secular political authority,” said Oliver, who co-authored the 2018 book “Enchanted America '' about conspiracy theories and false information.

Earlier in the pandemic it was the anti-malaria drug hydroxychloroquine that saw booming prescriptions after it was promoted by former President Donald Trump and others, only to be shown later that it did not work against COVID.

The fundamental elements of a medical conspiracy theory are that entities or individuals are working secretly to achieve some sinister goal such as ignoring important medical research or discouraging the use of a proven treatment.

The pandemic has brought about a marked rise in medical disinformation, largely through social media, to the point where up to 30% of people believe in some form of COVID conspiracies, according to a paper published in March in the journal PLOS One.

Those include claims that COVID is a hoax, was a pretext for mass vaccinations and is caused by 5G electromagnetic radiation.

The ivermectin conspiracy is "mainly amplified by the anti-vaccine community,” said the paper’s author, David Robert Grimes, a researcher affiliated with Dublin City University and the University of Oxford. Grimes also wrote the 2021 book “Good Thinking: Why Flawed Logic Puts Us All at Risk and How Critical Thinking Can Save the World,” which addresses medical conspiracy theories.

A Nov. 8 survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that 38% of Americans believed that the government was exaggerating the number of COVID deaths while another 22% were unsure if that was true; 18% believed that deaths due to the COVID vaccine were being intentionally hidden by the government while another 17% were unsure of that; and 7% believed the COVID vaccine contained a microchip while 8% were unsure of that.

High-profile supporters

In August, Republican Kentucky Sen. Rand Paul said hatred of former President Trump has kept researchers from looking into ivermectin as a COVID treatment.

"The hatred for Trump deranged these people so much that they're unwilling to objectively study it," Paul said to a group of constituents. Paul, an ophthalmologist, said he does not know if the drug works against COVID.

Kory called it a "war on repurposed drugs." He made that allegation in an interview with the Journal Sentinel prior to being asked about contracting COVID.

“You would have to believe that the pharmaceutical interests and government interests are separate," he said. "If the government agencies are correct (in their actions) then I’m wrong.”

As for the government campaign against the use of ivermectin to treat COVID-19, he said, “I don’t want to use the word conspiracy, but what I have seen is nothing but repeated efforts to convince the public that ivermectin is ineffective in fighting COVID-19.

“My entire year,” he said, “has been spent watching the distortions and manipulations about ivermectin.”

Kory, a Wisconsin-based pulmonary critical care specialist, said he has treated between 200 and 300 COVID-19 patients with ivermectin.

“Only one or two did go to the hospital, but they got to me late, about 10 to 12 days into the illness,” Kory said. He said the one or two who did go to the hospital only required short stays before being discharged.

When later asked about his own case of COVID, Kory issued a statement. “The most important event that occurred between my testimony (at Johnson's Dec. 8 hearing) and my getting sick was the delta variant," he said, explaining that the variant floods the body with a much larger amount of the virus than previous versions of SARS-CoV-2.

At Johnson’s Dec. 8 Senate hearing, Kory called ivermectin a “miracle drug.” He said: “It basically obliterates transmission of this virus. “If you take it, you will not get sick.”

Reports of death threats

But while some early ivermectin research showed promise, many of the studies were considered to be of lower quality. And some recent research has found that the drug is not effective against COVID:

For example, a July paper involving a clinical trial of 501 people published in the journal BMC Infectious Diseases found ivermectin had no significant effect on preventing hospitalization of COVID patients. And those who got the drug required mechanical ventilation earlier in their treatment.

And in August, researchers at McMaster University in Canada presented what they say is the largest randomized clinical trial with results to date of ivermectin in 1,355 people with COVID. The trial, which was conducted in Brazil, found no significant benefit in reducing the need to undergo extended emergency room observation or hospitalization. They also found no significant mortality benefit.

The results were presented at an online forum sponsored by NIH and have not yet been published or peer reviewed.

In addition to the big NIH clinical trial, a large clinical trial of ivermectin is underway in Great Britain, but the McMaster University trial suggests that ivermectin is not a miracle pill and is very unlikely to have substantial benefit as a COVID treatment, said F. Perry Wilson, an associate professor of medicine at Yale School of Medicine, who was not part of the trial and who teaches a course at Yale on how to understand medical research. Wilson said he is concerned the ivermectin conspiracy theory gives people permission not to change their behavior such as getting vaccinated or wearing a mask.

When COVID research results in findings that people don't like, it may lead to ugliness directed at the researchers.

Shortly after presenting the study, McMaster University researcher Edward Mills said he got death threats.

“Some people are very unhappy about the findings,” said Mills, a professor of health research methods, evidence and impact. “They believe the drug worked. It has kind of shaken their belief system. It makes them angry.”

Death threats were received by 15% of 321 responding scientists in several countries, including the U.S., who responded to an October survey conducted by the journal Nature. The scientists had given media interviews about COVID. Another 22% said they got threats of physical or sexual violence.

David Boulware, a researcher at the University of Minnesota, said he first encountered hate mail last year when he worked on studies of hydroxychloroquine and COVID.

"The hydroxychloroquine people were clearly very unhappy that the trials showed that it didn't work for (prevention) or for early treatment," said Boulware, a professor of medicine. "There was a little bit of hate mail about how I'm causing a genocide."

Then, Boulware set up a clinical trial of ivermectin. That trial still is going on, but every time a newspaper article described the trial, the scientists involved got more hate mail, he said. Boulware found himself being compared to the infamous Nazi doctor Josef Mengele by people who believed it was unethical to conduct a randomized controlled trial of ivermectin "because it clearly works ... .”

The nastiness of responses to COVID-19-related trials finally convinced Boulware to take his office phone number off the Internet.

THANK YOU: Subscribers' support makes this work possible. Help us share the knowledge by buying a gift subscription.

DOWNLOAD THE APP: Get the latest news, sports and more

This article originally appeared on Milwaukee Journal Sentinel: Ivermectin seducing many as prescriptions and poisonings surge