‘The long term fight’: How Democrats plan to save voting rights

For half a century, Virginia was subject to rules under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 preventing states from imposing discriminatory laws that disenfranchised generations of voters.

In 2013, those guardrails were removed by the US Supreme Court, gutting a critical provision from the landmark civil rights law that requires states with histories of discrimination to get federal approval before imposing new rules.

So Virginia wrote its own.

Signed into law this spring, the Voting Rights Act of Virginia – the first southern state with its own version of the law – imposes on itself the same standards for writing new election rules under previous federal preclearance guidelines.

Within the last two years, the state’s Democrat-controlled General Assembly and Governor Ralph Northam have secured no-excuse mail-in ballots, repealed a restrictive voter ID law, enacted automatic voter registration and made Election Day a state holiday – marking a radical expansion of voting rights that advocates now are fighting to protect, or risk undermining generational progress against a tide of suppressive voting laws across the US.

“It can go away,” said the bill’s author, Virginia Representative Marcia Price.

“I think people sometimes don’t really understand how fragile this process really is,” she told The Independent. “In my eyes, America’s democracy started in 1965 and not a day before that. What are we doing to protect it, feed it and nurture it? I think the next step is continuing to protect the progress that we’ve made and fighting back against the big lie.”

That lie is coursing through state houses, campaign trails and in the halls of Congress, splintering into myths about the failed insurrection it inspired at the Capitol and conspiracy theories fuelling so-called “audits” of state-level election results.

Emboldened by Donald Trump’s baseless “stolen election” narrative under the guise of preserving “election integrity” and “voter confidence” despite record-setting turnout in 2020 elections, Republican leaders in at least 17 states have enacted at least 28 new laws so far this year that restrict access to the ballot.

A parallel effort from GOP lawmakers has seen more than 200 bills in 41 states that give themselves more authority over the electoral process, with the potential to overturn the results. At least 24 of those bills have been signed into law.

A coordinated wave of nearly 400 pieces of copycat legislation filed by Republican lawmakers flooded state legislatures within the first few months of 2021 in the aftermath of 2020 elections that saw GOP losses and the former president’s persistent lie that widespread fraud and “irregularities” marred the outcomes.

Despite Republicans’ voter suppression campaign, more than half of the US will have greater access to the ballot in upcoming elections, as several states enshrine into law measures that expand early voting windows, eligibility for mail-in ballots, and better access for voters with disabilities.

“In order to confront the sweeping attacks on the ballot box we are seeing in states across the country, we must also amplify and celebrate the positive steps forward,” said Nevada Attorney General Aaron Ford, whose state passed automatic voter registration and expanded mail-in voting.

At least five laws in six other states expand access to mail-in drop box access or ballot drop-off locations, and at least six states have passed laws to make voting easier for people with disabilities.

This year, Virginia passed nine such laws, the most of any state.

The measures enshrine or build upon election measures that encouraged unprecedented turnout in 2020 despite the coronavirus pandemic that threatened to keep people away from in-person voting.

Virginia created a 45-day window for no-excuse mail-in ballots, among the largest in the US. More than 2.8 million Virginia voters cast their ballots before Election Day that year – nearly five times as many as in 2016.

The state’s new Voting Rights Act – an effort led by Black women in the state legislature and civil rights organisations – requires election officials to receive public feedback and approval from the state’s attorney general before drawing up any new election rules, like moving polling locations, and it allows voters to sue the state for suppressing their vote.

It is “unapologetically about protecting voting communities that have been targeted by suppression since voting began in the colonies,” Ms Price told The Independent.

Advocates see Virginia as a model, but the fight to protect and expand ballot access will not end with the passage of one law. The result of expanded ballot access in some states and restrictive laws in others could risk widening a gulf of inequality and discrimination, through measures depending on how lawmakers reacted to the former president’s election lies and the public health crisis.

Without any federal standards, and winnowing civil rights protections, Americans’ experience at the ballot box – from how long they wait in line to whether their vote counts at all – could vary dramatically.

Virginia – hailed as the provenance of American democracy – has, like many states, a long and violent history denying its residents the right to vote.

African Americans in the state legally cast their ballots for the first time in 1867 followed by their election to state and local governments in the aftermath of the Civil War – a period undermined by decades of Jim Crow-era disenfranchisement, from “black codes” that subjected harsh penalties for newly freed Black Americans for crimes like loitering or breaking curfew, ensuring they would remain in chains for decades to follow, to discriminatory poll taxes and literacy tests to obstruct their access to the ballot box.

At the peak of the Civil Rights movement, the NAACP filed more lawsuits in Virginia than in any other state, resulting in precedent-setting cases on segregation and interracial marriage.

Poll taxes remained in place until 1966, when the US Supreme Court ruled in favour of Norfolk, Virginia civil rights activist Evelyn Butts. It wasn’t until 2019 that language governing them was stripped from the books.

From 2010 to 2013, before the Supreme Court issued a blow to the Voting Rights Act’s preclearance mandate, Virginia officials sought more than 1,300 changes to election procedures, district maps and polling precincts, all of which required federal approval to determine their discriminatory impacts before they could go into effect.

Ms Price, who sponsored legislation to remove the vestiges of discriminatory poll taxes from state codes, points to a legacy of Black activism standing in stark contrast to perennial threats to the right to vote.

“If we look at the systems that have historically disenfranchised us for years, we can’t have hope in the systems,” she told The Independent.

“It’s not blind faith or trust in humanity that got us the Voting Rights Act [of 1965],” she said. “It was literal blood, sweat and tears. … I don’t have the luxury to believe in the best in humanity. I need the laws to protect my rights, my community’s rights and everybody’s rights. I have hope in the people who have put their lives on the line because we’ve had to do that for generations to get the changes that we needed. That is what keeps us going.”

In a major test of what remains of the federal Voting Rights Act, the Supreme Court recently upheld two Arizona laws that voting rights advocates argued have disproportionately hurt minority voters, a decision that will likely make it more difficult to challenge recent Republican-backed laws restricting voting access, and the high court’s second decision within the decade to undermine key elements of a civil rights law with a bloody road to its passage.

The path to restoring and extending federal voting rights protections has become increasingly unclear. Republican blockades in Congress are certain, and the White House has turned to asking for grassroots support and the US Department of Justice to out-organise and litigate away the wave of GOP legislation coming to the states ahead of critical 2022 midterm elections.

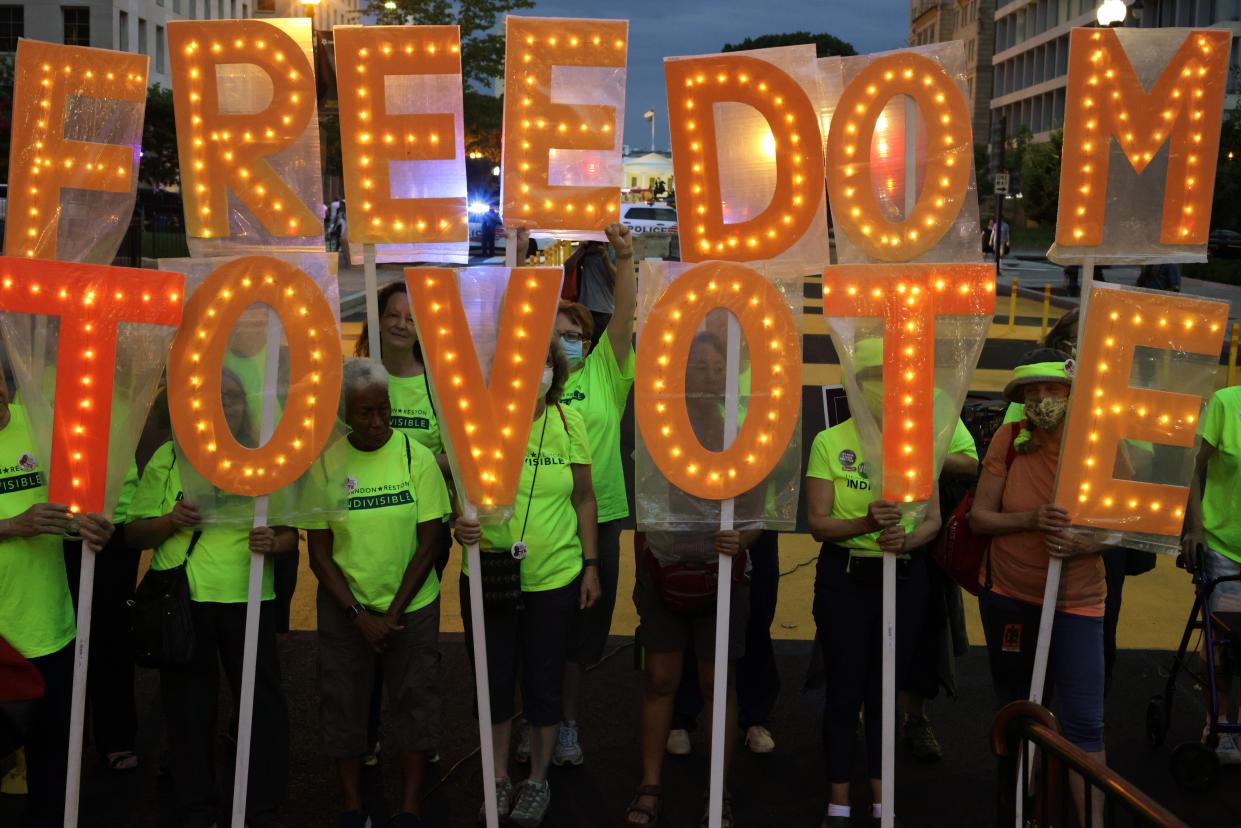

Nearly 100 people were arrested in the nation’s capital this month while protesting to demand Congress pass two pieces of voting rights legislation at the centre of the legislative battle to protect the right to vote.

Two members of the Congressional Black Caucus – Joyce Beatty and Hank Johnson – were among them.

More than 75 people were arrested during a Poor People’s Campaign demonstration outside the Supreme Court on 19 July.

The campaign, along with Black Voters Matter and several civil rights groups, have toured the US in a revival of Civil Rights-era freedom rides against voter suppression and to register people to vote.

A group of Democratic state lawmakers also arrived in Washington DC this month from Texas in a high-profile, last-ditch effort to block restrictive Republican-sponsored elections legislation in the Lone Star state while also lobbying members of Congress to pass federal voting rights protections during their nearly month-long stay.

On 22 July, a group of more than 150 civil rights groups appealed to the White House for Joe Biden’s help passing the For The People Act and a restoration of the Voting Rights Act “by whatever means necessary.”

Despite Mr Biden’s insistence that protecting and expanding the right to vote remains a “test of our time” and a definitive battle for his presidency, activists have found themselves swimming upstream against a president whose rhetoric on voting rights has not matched his demands.

Civil rights leaders and a growing body of Democratic lawmakers have found themselves at odds with a White House that continues to suggest a bipartisan path is possible against a tide of explicitly partisan attacks to undermine ballot access.

“We cannot and should not have to organise our way out of the attacks and restrictions on voting that lawmakers are passing and proposing at the state level,” the groups said in a letter on 22 July.

Kristin Fulwylie, managing director for Equal Ground, is already organising an awareness campaign ahead of upcoming elections in Florida’s Orange and Pinellas counties, serving as “practice” runs for 2022 elections after Governor Ron DeSantis signed his state’s restrictive elections bill into law.

The law rolls back mail-in ballot eligibility and drop box availability and restricts how many ballots can be collected on behalf of other voters, among other measures.

Florida’s law “purports to solve problems that do not exist [and] caters to a dangerous lie about the 2020 election that threatens our most basic democratic values,” wrote the plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed by voting rights attorney Marc Elias on behalf of the League of Women Voters.

Voting by mail has been a powerful and popular practice in the state, with widespread support from both Democrats and Republicans following a 1988 US Senate race that saw the GOP candidate eke out a win thanks to late-arriving absentee ballot counts.

But Mr Trump – who has also cast ballots by mail in the state – repeatedly attacked mail-in voting as a “hoax” and “corrupt” before a single ballot was even cast in the 2020 elections.

The state’s Republican lawmakers, governor and members of Congress, who have all in some part won their seats with mail-in ballots, all followed suit. In the 2020 elections, more than 1.5 million Republican voters cast votes by mail, and more than 1.9 million voted early.

The number of Democrats who voted by mail – in the middle of a coronavirus pandemic, which primed crowded in-person polling locations for possible outbreaks – reached nearly 2.2 million.

Organisers are distributing voting rights information cards and holding phone and text banking campaigns to explain changes to the law, how to register to vote and where to find a polling location, and encourage voters to cast their ballots early, Ms Fulwylie said.

“It’s one way to try to fight back those fears,” she told The Independent.

“This is going to be a long-term fight,” said Lala Wu of Sister District, which campaigns to elect Democratic candidates to state legislatures. “These organisations are on the front lines … They need to be prepared for this fight in the long term.”

Lawmakers and voting rights advocates are bracing for partisan redistricting battles in the months ahead, with US Census data redrawing political boundaries that could erode the political power of communities of colour.

The Democratic National Committee is also pumping $25m into get-out-the-vote campaigns to “register voters, to educate voters, to turn out voters, to protect voters,” Vice President Kamala Harris said.

Meanwhile, a select committee in the House of Representatives to investigate the 6 January Capitol riot – one powered by the lie that is also baked into the text of Republicans’ restrictive voting laws – will likely continue to trace the nation’s history of violent voter suppression to the previous administration and its imprint on the current state of the GOP.

“I know a lot of Black people who were watching those videos … and we’ve seen domestic terrorism before and connect it to white robes,” said Ms Price, the Virginia legislator.

“We don’t have to be convinced that racism is still alive and well, if you see some of the hate mail that Black legislators are getting just for opening their mouths to encourage people to use their rights,” she said. “Anyone saying these protections are not needed are not living in the America and through the American experience I am. But I do know so many of us are energised in this fight.”