The Longest Strike in U.S. History

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

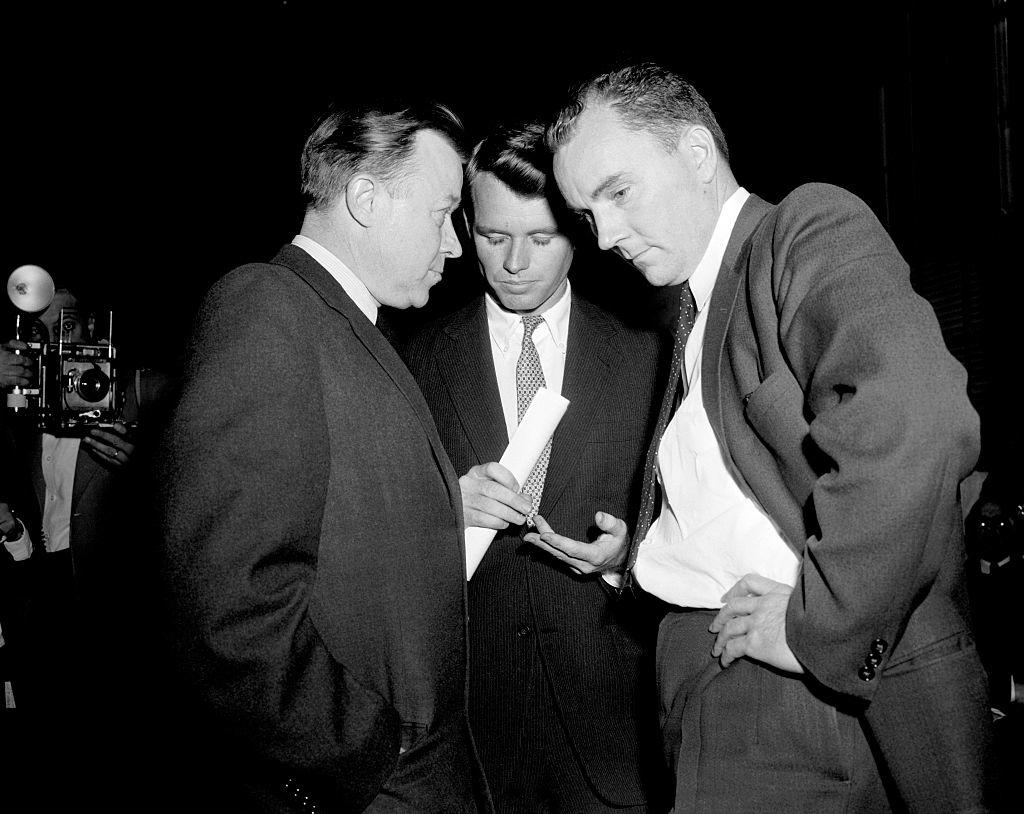

On Mar. 27, 1958, Walter Reuther (left), president of the UAW, goes into a huddle with Senate Rackets Committee Counsel Robert F. Kennedy (center) and Jack Conway, assistant to the UAW Chief, before Reuther testified in the Senate Committee's probe of the 4-year-old strike by the UAW against the Kohler Company, a Sheboygan, Wisconsin plumbing fixture firm. Reuther opened his testimony by charging that the Kohler Company has refused to recognize the law during the bitter strike. Credit - Bettmann Archive

The ongoing writers and actors strike halting the television and movie business has already surpassed 100 days as Labor Day approaches. But so far, it’s still nowhere near as long as the longest strike in U.S. history.

Labor historians say the longest strike the nation has ever seen was the Kohler strike, which lasted for 11 years from 1954 to 1965.

Kohler is one of the biggest manufacturers of plumbing fixtures in the U.S. The Sheboygan, Wis., area was essentially a company town with its own schools and recreation facilities and red brick houses with green lawns. The Mar. 17, 1958, issue of TIME reported that the company's president Herbert Kohler “considers himself a just and benevolent employer” and that “this monument to paternalism, incorporated as the Village of Kohler may rank as the world's most attractive company town.”

More From TIME

But workers wanted more than a nice neighborhood. They pushed for a contract with higher wages, protections for the most senior employees during layoffs, and union dues deducted from paychecks. “These are employees who are trying to get their union recognized and are looking for a contract,” says Elizabeth Shermer, professor of History at Loyola University Chicago.

Read More: 'They Are Doing Bad Things to Good People': Fran Drescher on Why SAG-AFTRA Is Striking

The strike officially began on April 5, 1954, and while workers were prepared for a fight, no one expected the strike to become a long and ugly battle that would last more than a decade. The United Auto Workers union (UAW) and its head Walter Reuther, considered one of the most charismatic union leaders of the era, helped the Kohler strikers stay afloat with a strike fund. For the first two years, the UAW gave strikers enough money for food, medical care, and $25 a week of “jingling money,” according to TIME, but as the strike dragged on, the funds were cut back. Some workers had to leave town and find new jobs elsewhere. After initially shutting down for the first two months of the strike, Kohler brought in nonunion workers to replace those that had left.

The UAW also organized a nationwide boycott of Kohler products among plumbers, contractors, and municipal officers, from Boston to Los Angeles.

The battle between management and workers spilled out into the streets and became increasingly acrimonious. Gas masks were a common sight at pickets, according to TIME, and in one confrontation, 300 people were arrested. The strike tore Sheboygan apart. There were families where strikers ostracized a close relative who crossed the picket line. As a Mar. 17, 1958, issue of TIME magazine described the bitterness of the strike four years in, with 2,800 of 3,300 workers striking:

While the Kohler strike's length gives it a unique place in U.S. history, it fit into a larger pattern of labor movements at the time. Strikes were common in the 1950s. “This was the height of postwar union strength,” says Joseph A. McCartin, professor of History at Georgetown. “Almost 35% of non-agricultural workers in the country at that time were represented by unions.” By comparison, 10% of wage and salary workers were members of unions in 2022—the lowest rate on record—and the rate for private sector workers was 6 percent.

Nelson Lichtenstein, a historian at UC Santa Barbara, argues that while there’s been a “Renaissance of union sentiment” in recent years—from efforts to unionize Starbucks and Amazon to the Hollywood strike— it’s “minuscule compared to what was happening in the 50s.” Lichtenstein says, “Many, on the one hand, think of the 50s as a period of social harmony. We think of Leave It to Beaver—but in fact, there were strikes and strikes and strikes and strikes.”

The Kohler strike came to an end in the early 1960s, when the National Labor Relations Board found Kohler guilty of unfair labor practices. The strike technically ended in 1962, but the labor dispute didn’t fully resolve until 1965, when new Kohler management came in and paid wages that the strikers had been demanding and put more money in their pension funds. TIME reported at the time that the boycott was only “partially successful,” despite the UAW pouring $12 million into the effort, and essentially declared victory for Kohler management: “Despite the most extensive boycott campaign ever mounted by organized labor, the effect of the long dispute on the company was hardly shattering; Kohler today is still a leader in the industry.”

Some of the anti-union tactics in today's Hollywood strike can be traced back to the Kohler era. Lichtenstein explains that in the late 1940s and early 1950s, companies like Kohler would publicize their offer to strikers to increase pressure on them to accept. In a modern-day parallel, he argues, the Hollywood studios publicized their offer to striking writers on Aug. 22.

As McCartin explains the legacy of the Kohler strike: “What makes the Kohler strike interesting to consider today is it points out how some of the same resistance continues among leaders of some of America's biggest and most successful businesses.”

Write to Olivia B. Waxman at olivia.waxman@time.com.