Longtime First Union bank CEO Ed Crutchfield, an influential force in Charlotte, dies

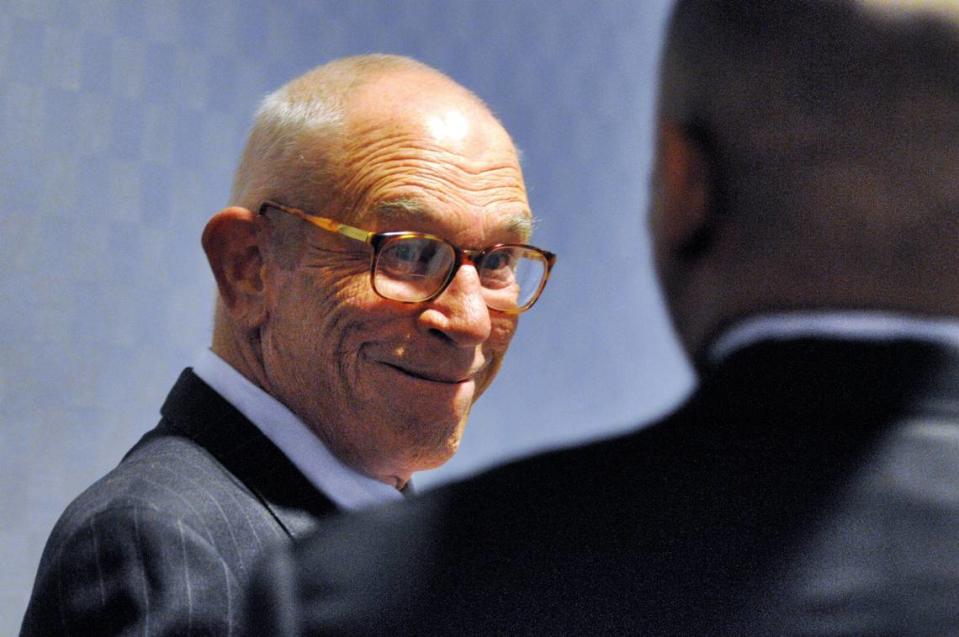

Ed Crutchfield, who took charge of Charlotte-based First Union and forged a national banking powerhouse while also championing the city’s growth, died Tuesday at age 82.

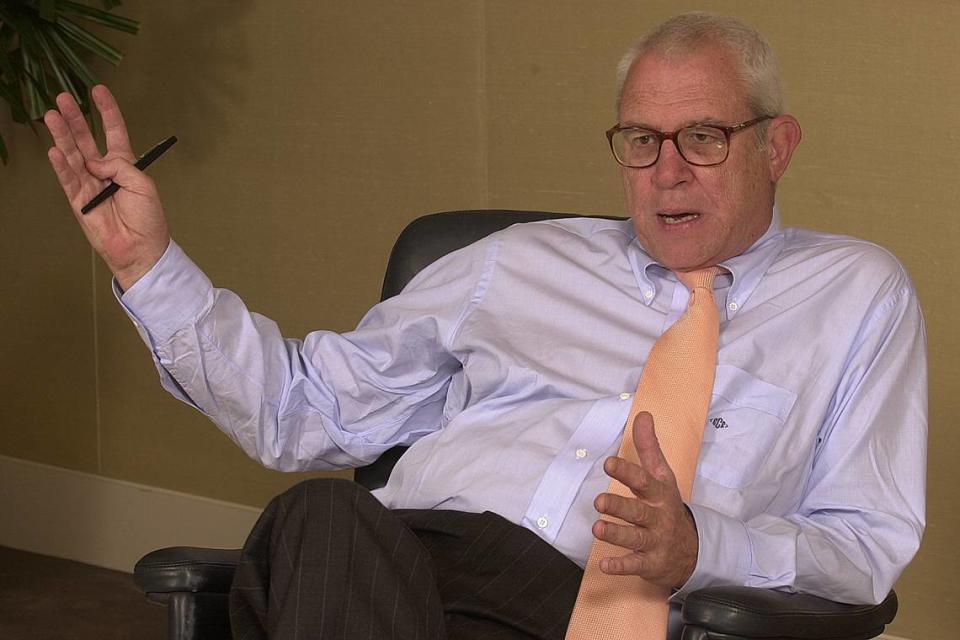

In 15 years as CEO of a bank that is now part of Wells Fargo, Crutchfield made more than 80 acquisitions to create the nation’s No. 6 bank by the time he retired in 2001.

Wells Fargo is based in San Francisco and has some 230,000 employees nationwide. Its largest employment hub is in the Charlotte area, where it employs more than 27,000 people. Much of that is a legacy of Crutchfield’s construction of First Union.

The late Ed Crutchfield built First Union into a banking giant. A look at his career

“He was my best friend and a fantastic dad and a hero to me,” his son, Elliott Crutchfield told The Charlotte Observer Tuesday night. “On a broader basis, I can tell you from inside the house, he gave it all he had for the bank and by extension Charlotte.

“And I can tell you he took significant steps to make sure the bank was headquartered here (in Charlotte) when others had some other ideas. It was important to him that that be the case.”

Ed Crutchfield died peacefully at his home in Vero Beach, Fla., after a battle with dementia, his son said.

Competing and collaborating in Charlotte

One of Charlotte’s leading businessmen in the last quarter of the 20th century, Crutchfield built a major bank headquarters in the city, and — despite a professional rivalry — was a frequent partner of then-Bank of America CEO Hugh McColl when it came to Charlotte’s civic growth.

McColl told the Observer Wednesday that he and Crutchfield competed intensely in trying to gobble up banks around the nation, with each winning their share. First Union snapped up Atlantic Bank in Florida just as McColl was in discussions with them, while NationsBank, as McColl’s company was then known, won Boatmen’s Bancshares in St. Louis, for example.

“It was quite competitive,” McColl said. “We chased each other around the country buying companies.”

That competition turned to collaboration, though, when it came to building up Charlotte. The two would back each other’s projects, whether it be supporting the symphony, Johnson C. Smith University or any of the dozens of other efforts.

“Everyone thinks we were enemies, but that wasn’t really true,” McColl said. “We both ran our companies and got along fine on civic matters. And we both disliked Wachovia intensely.”

Crutchfield retired earlier than expected at age 59 to successfully fight lymphoma, turning the company over to his hand-picked successor, Ken Thompson. First Union later merged with Winston-Salem’s Wachovia and was bought by Wells Fargo after the bank nearly collapsed in the 2008 financial crisis.

Some of Crutchfield’s deals were duds. But he was often praised in Charlotte for helping the city become a major banking center and particularly for developing much of the southern half of uptown.

“Ed Crutchfield has been tremendously admired by the banking community, not just in North Carolina, but across the country, because he didn’t just sit on the sidelines and watch the parade go by. He was a drum major,’’ Thad Woodard, head of the N.C. Bankers Association, said when Crutchfield retired.

Ed Crutchfield NC ties

Born in Detroit, Crutchfield was raised in Albemarle in Stanly County, about an hour east of Charlotte. His mother was a school teacher and his father worked as an FBI agent, lawyer and county judge, his son said.

After graduating from Davidson College and the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, Crutchfield joined First Union as a bond trader at age 23.

He rose quickly through the ranks, becoming president in 1973 and CEO in 1984, succeeding Cliff Cameron.

Crutchfield would spend much of his career buying banks. Soon after taking charge, he merged First Union with Greensboro-based Northwestern Financial Corp.

It was the biggest bank merger in state history at the time and formed North Carolina’s second-largest bank.

His dealmaking days were full of colorful stories that earned him the nickname “Fast Eddie” from Wall Street analysts, some of whom fretted about his expensive purchases.

One of his dogs, Bud, became a good-luck charm after barely surviving being hit by a car in 1995 while Crutchfield awaited news on a bid for First Fidelity Bancorp. First Union bought the Newark, N.J., bank for $5.4 billion — the biggest U.S. bank acquisition at the time.

In 1997, the dealmaker bragged about the technique he used to buy Signet Banking Corp. of Richmond, Va., another key acquisition.

To get the bank’s management to sell, he said, “I just kept stacking billion-dollar bills on the table.’’

Wall Street style in Charlotte

In the coming year, he would make even more deals, ultimately expanding First Union from Connecticut to Key West, Florida, and into new business lines.

Crutchfield paid $19.8 billion for Philadelphia’s last big bank, CoreStates Financial, in 1998. He set a new record for the most expensive deal in U.S. banking history. The same year he also spent $2.1 billion on a consumer finance company, The Money Store.

He also built a Wall Street-style capital markets business at First Union, recruiting investment bankers, many from the Northeast, to the Queen City.

Some of these deals would have their pitfalls.

He paid a high price for CoreStates and when Crutchfield moved quickly to integrate operations the rapid pace spawned computer glitches that sent customers fleeing. A revenue shortfall at CoreStates and an accounting change at the Money Store led to lower earnings estimates that soured the company’s reputation on Wall Street in the late 1990s.

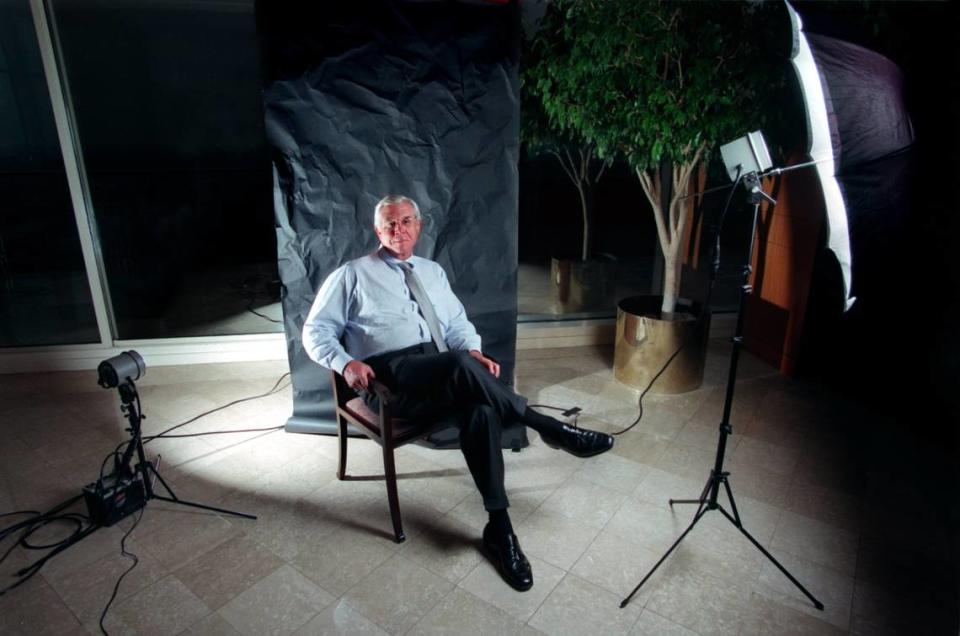

In 2000, Crutchfield at age 59 was diagnosed with lymphoma and handed his CEO title to Thompson, who quickly restructured the company and improved customer service. Crutchfield went through chemotherapy and beat the disease, but gave up his chairman post in March 2001, leaving behind the bank he forged.

Thompson merged First Union with Winston-Salem’s Wachovia in 2001 and kept the smaller company’s more-respected name.

“To me the biggest thrill has been seeing the company start when nobody was giving us a plugged nickel for our chances, and at least as of today, pulling it off,’’ Crutchfield told the Observer in an interview before his retirement. “That’s been a kick.’’

Ed Crutchfield’s civic involvement

Although known for his hard-charging ways, Crutchfield once said an admonishment from his mother, Katherine, encouraged him to develop a warm workplace for his thousands of employees. He once made news when he banned voicemail at the company to encourage human contact.

In 1996, he married Barbara Massa, First Union’s former director of corporate communications. He had two grown children. He was divorced from his first wife, Nancy.

Besides his banking accomplishments, Crutchfield also was known for being part of “The Group’’ — a handful of businessmen who once helped shape Charlotte.

Although he was a fierce competitor with McColl, Crutchfield collaborated with him and other business leaders on community projects.

“I believe the last 20 years of focus on developing the uptown area of Charlotte has been appropriate,’’ he said in a 2003 letter to the Observer. “However, it is my belief that Charlotte-Mecklenburg should now shift its priority, focus and dollars in a major way to the issues of education and human services for young people.’’

In the late 1980s, he played a quiet but influential role during a campaign to diversify Charlotte’s then all-white country clubs.

In 1997, when five Mecklenburg County commissioners moved to cut funding to the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Arts & Science Council because of objections to gay characters and themes in a play, he got involved to diversify the board.

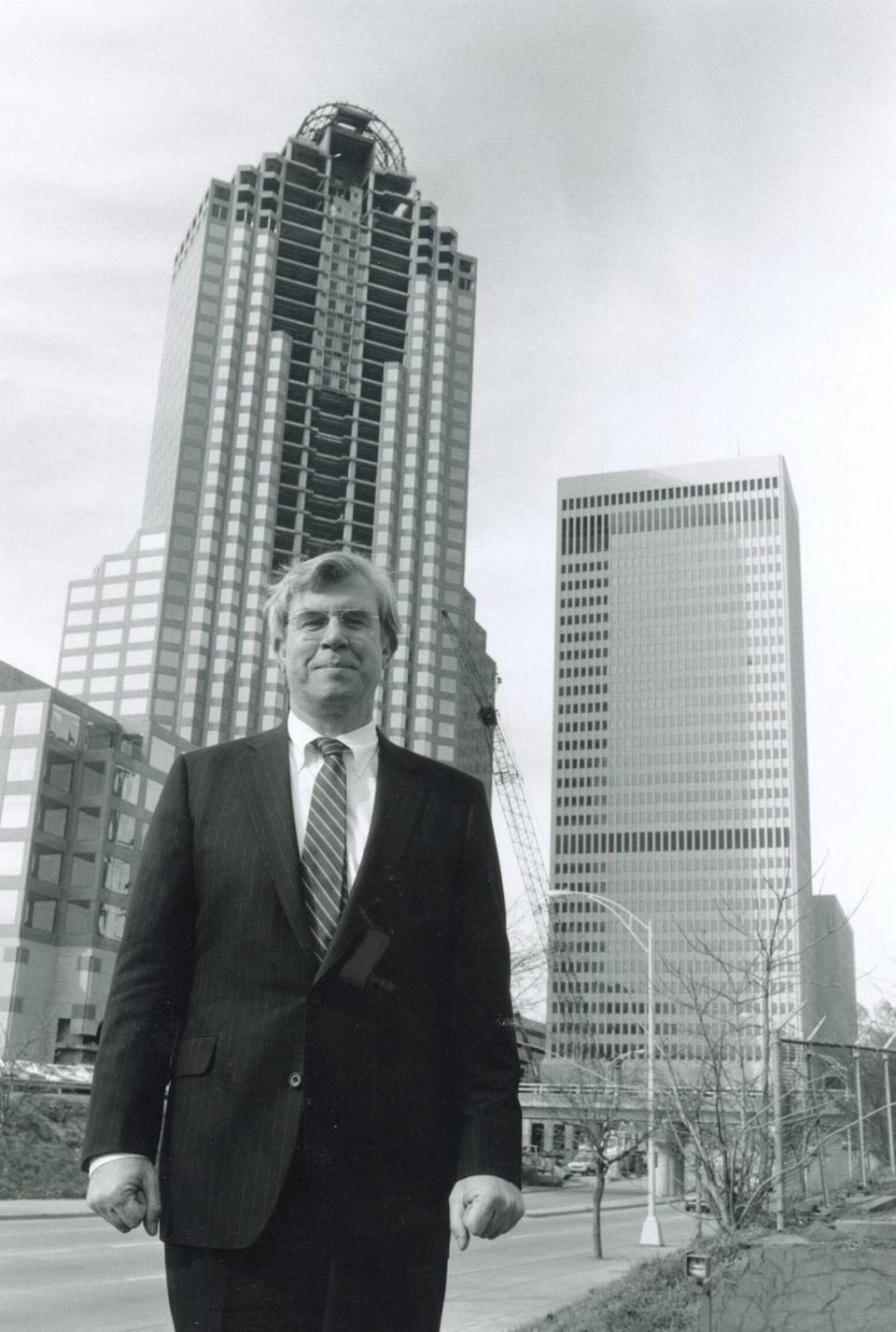

Like McColl, Crutchfield also left his mark by molding the city’s skyline. In 1988, the bank opened its 42-story headquarters tower on South College Street.

The Green park on South Tryon that hides an underground parking garage also was part of his vision. A proposed tower that would have topped McColl’s 60-story headquarters, however, never materialized.

“While he always knew that his major responsibility was looking out for First Union and its shareholders, he also understands the health of this community and the vitality of this community are good for business,’’ the late Mecklenburg County Commissioners Chairman Parks Helms once told the Observer.

In his retirement, Crutchfield spent time in Charlotte, Florida and the N.C. mountains. He enjoyed flyfishing with his wife and spending time with his grandchildren.

Observer editors Taylor Batten and Adam Bell, and former Observer reporters Rick Rothacker, Hannah Lang and Austin Weinstein, and Observer archives, contributed to this report.

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the professional background of Crutchfield’s father.