A longtime Latino political strategist — and dad of a famous son — is writing a memoir

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Nowadays, he may be introduced as Lin-Manuel Miranda's dad, but decades before his son became a Broadway sensation and a household name, Luis Miranda had carved an influential role in local, state and national Latino advocacy and politics.

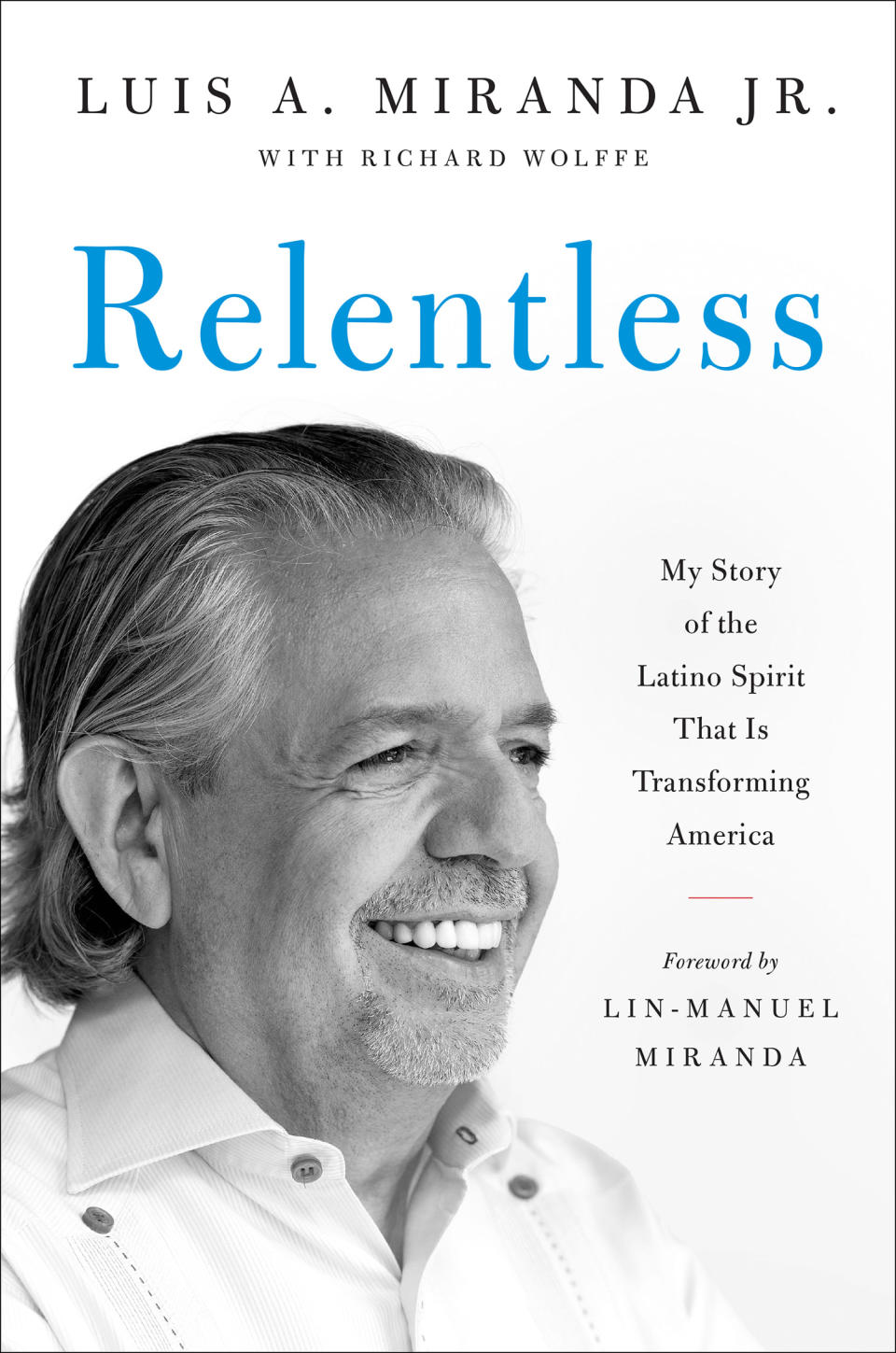

The veteran Democratic political strategist and founder of one of the largest Latino nonprofit groups is taking stock of his and his family's trajectory, his work and his take on the diverse and growing Latino electorate in his memoir, "Relentless: My Story of the Latino Spirit That Is Transforming America," which will be published in both English and Spanish next May by Hachette Books.

When asked why he decided to write it now, Miranda gave two reasons as he spoke to NBC News last week ahead of the book's announcement.

One, he said, was finding himself increasingly "getting frustrated" over the analysis of the Latino vote after Donald Trump's election as president, when it seemed to him that many had "just discovered" that there are segments of the Latino population that vote Republican, despite generations of Mexican American, Cuban American and other voters consistently supporting GOP candidates. "They were making all these assumptions and judgments when they just didn't have the whole picture," he said.

"The second piece that hit me," Miranda, 69, said about his decision to write the memoir, "was that you're getting old and you are going to die."

When it came to what he was reading — and disagreeing with — regarding Latino voters and other issues, he said he told himself "it doesn't matter that you disagree; it just means that somebody else's voice is the one that is heard" if he didn't write his own account and put it on the record.

Born and raised in Puerto Rico, Miranda came to New York to pursue a graduate degree and pretty quickly fell into Latino community organizing and mobilization. He became director of the Office of Hispanic Affairs under then-Mayor Ed Koch and subsequently worked in different positions under several New York City mayors, including Rudolph Giuliani. In 1990, he founded the Hispanic Federation, one of the largest Latino nonprofit groups, and was a founding partner of the MirRam group, a Democratic political consulting group. His work with Democratic politicians has tracked changing Latino demographics, such as the growing Dominican American presence in New York and elsewhere and its first elected officials.

But Miranda is clear about how Lin-Manuel Miranda's name recognition and influence following his success with "Hamilton" and later projects like the Disney movie "Encanto" have given the family a big platform for a host of Latino and national issues, such as raising money for Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria or pandemic relief.

"My son got a huge mic, and the second he got a huge mic, he shared it with all of us —and allowed to work as a collective, because we think so much alike," Miranda said, speaking not just about his work and advocacy, but also the work of his wife, Luz Towns-Miranda, a clinical psychologist and professor who has focused on foster care and who's active in reproductive rights.

Miranda said he's been asked why he doesn't write a book about "raising a genius" and he said he has no interest and doesn't "have a clue — we just raised kids and we did it the Puerto Rican way."

Miranda's professional arc starts with his migration to the mainland from Puerto Rico. The Caribbean island archipelago is a U.S. territory, so while Puerto Ricans like Miranda are not immigrants in the legal sense of the word, "when you came here —for the regular New Yorker, there was really no difference" in the way he was perceived, he said in his still-accented English.

Miranda said that, as a young man, his initial focus was on creating consciousness of Puerto Rico's colonial status and the island's needs, but as he spent time in New York and as Puerto Ricans like him were increasingly called "Latinos," he spent time "figuring out what that means" and shifting to ways to work collectively.

When asked about the changes he's seen in the decades he's been working in politics, including more political division and extreme points of view, Miranda laughed and said that unlike young people, "old people cannot afford to be pessimistic."

“We come here to look for different things,” he said. “We need to spend time looking for the things that unite us and are going to help us move forward.”

This article was originally published on NBCNews.com