Look back at Hurricane of ’38: Downtown Norwich flooded with 11 feet of water

Thursday, Sept. 21 marks the 85th anniversary of the Hurricane of 1938. It was a storm that followed a path that hurricanes were not supposed to travel. Arriving in an area where hurricanes, up to the point, were not supposed to happen. Hurricanes had been known as storms of the Caribbean and Florida that veered out to sea at the Carolinas. Hurricanes did not happen here.

And yet, it came, speeding up the East Coast like an express train. Knocking out communications along the way. Preventing any advance warning.

It came, making landfall in Long Island a little after noon. It came, hitting Southern Connecticut a few hours later with a force unprecedented, catching everyone off guard. It came, downing the beautiful huge elms and chestnut trees of Norwich. It came, blasting with a 121 mph wind that you could barely walk through, a wind you needed to shout above to be heard. It came, with a wind that gusted up to 186 mph. A wind that crumbled buildings like cardboard boxes, that blew out the whole front of the Broadway School, that sent the clock of City Hall sailing through the air. It left the streets of the Rose City a mass of twisted sheet metal, strands of electrical wires, crushed automobiles, broken glass, fallen shop signs, and shattered church steeples — impassable, except by climbing over and under the huge trunks and limbs of trees, their massive roots reaching up to the darkened skies above.

Destruction everywhere in the city

The wind left factory floors exposed to the elements, their roofs peeled away. At the Falls Mill, Ponemah Mill, Saxon Woolen Mill and the Glen Woolen Mill, the looms, huge spools of thread, and bolts of fabric were all soaked, blown apart — destroyed.

The gold cross on St. Patrick’s Cathedral sailed away, and the stained glass windows were blown in. A large portion of the church’s slate roof blew off, with the slates flying like through the air like the tins of Frisbee pies.

The storm toppled barns into fields, lifted chicken coops into the air and threw them into trees, with their residents still inside — squawking. In the midst of the storm, New London caught fire and a 10-block section of Bank Street burned.

The storm blew for several hours, stopped briefly, and then blew again as the second half wailed over New England, raking over what was left standing from before.

Tidal surge followed the storm and flooded downtown

When the storm subsided, and it finally seemed safe, those who chose to venture out were met with a tidal surge. But this was not just any storm surge at a high tide. This was a storm surge on top of an astronomical tide of the autumn equinox — Sept. 21. A tide that measured between 17 to 25 feet from Southern Connecticut up to Gloucester, Massachusetts. A tide that rolled in waves that were recorded at 50 feet high, although, according to some witnesses around Watch Hill, Rhode Island, perhaps up to 80 feet tall.

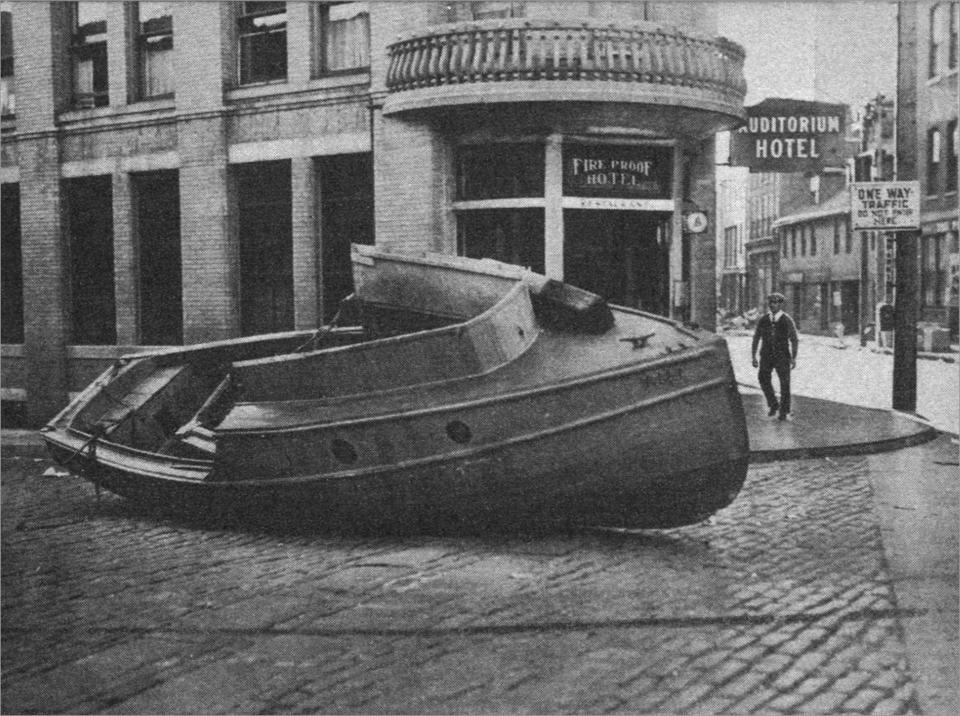

In Norwich, the tide raced up all three rivers and flooded downtown with 11 feet of water, washing boats into Franklin Square, including a cabin cruiser that floated up Market Street before running aground by the Auditorium Hotel. The water rose quickly until it reached just below the marquee on the Palace Theater. It flooded bridges or, as in the case of the Eight Street Bridge, washed them completely away. Large pieces of the bridge were later found just north of the drawbridge in New London, 13 miles away.

Water covered downtown Providence in 20 feet of water. It washed huge tankers inland, leaving them perched on the railroad tracks in New London, and it washed a train full of passengers off the tracks in Stonington.

The storm surge washed away whole beachside communities that had stood at Bluff Point, Ocean Beach, Napatree Point and Misquamicut. Many of the cottages were washed out into Long Island Sound. The rest were left as piles of wrecked lumber.

Storm's effects still remain today

The tide washed away the people who tried to ride out the storm, particularly at Watch Hill and Misquamicut, where at least 54 people were reported killed. The damage was so severe to these areas that the cities and states took over the beaches, leaving the land undeveloped, as it remains today.

The storm of ‘38 is still considered the most destructive hurricane in the recorded history of New England. It necessitated the creation of 50 Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps to clear all the downed timber over the next three years. It reshaped the shoreline from New York to Massachusetts. It decimated the the New England fishing fleet, destroying at least 2,600 vessels and damaging perhaps 3,370 more.

Over 8,900 buildings were destroyed in the storm, and another 15,000 were damaged. The storm injured more than 1,700 people throughout New England, and it killed at least 564 individuals, mostly along the shore.

Each year, the memory of this storm fades a little deeper into our community memory. Today on the 85th anniversary of the storm, it is good to remember the power of the 1938 hurricane and its impact on our area.

Christine Wisniewski lives in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, and works as a personal historian at Saving Stories. She is the author of "The Hurricane of 1938: Memories of the Storm of the Century."

This article originally appeared on The Bulletin: Hurricane of 1938 impacted New England, flooded downtown Norwich