Looking back, 20 years after Evansville stadium for Dodgers' minor leaguers fell through

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

EVANSVILLE — Bosse Field is considered to be hallowed ground.

A monument to the city, the nearly 106-year-old ballpark is the third-oldest still in use for professional baseball nationwide. So many famous lives have passed through its gates, including more than 100 Hall of Famers and the cast of “A League of Their Own.” It’s more than just a baseball stadium for generations spanning the days of the Evansville River Rats to the Braves, Triplets and now Otters.

Had matters shaken out differently 20 years ago, it already might have been forgotten in history.

A contentious issue split this community in early 2003 when city officials were planning to build a new Downtown baseball stadium to house a Los Angeles Dodgers minor-league team. The ownership group included MLB greats Don Mattingly and Cal Ripken Jr., as well as former Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda.

Impressive, right?

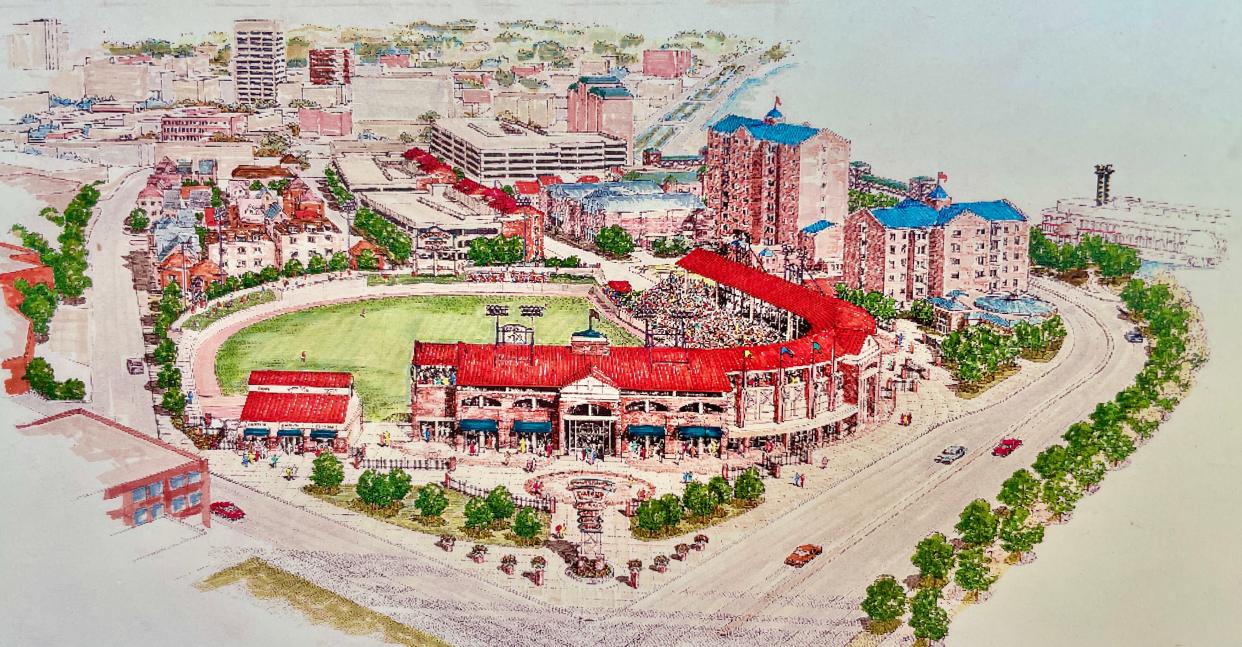

Home plate would’ve been nestled between the intersection of Second Street and Fulton Avenue just south of the Lloyd Expressway. A beautiful, $25 million ballpark along the riverfront. It would’ve revitalized Downtown sooner than it has today — more restaurants, bars, shops, apartments.

Imagine a full stadium thumping in the heart of the city on a hot summer night.

Backed by those big baseball names and majority owner Dave Heller, affiliated minor-league ball was set to return to town for Opening Day 2004. Bosse Field lost its affiliated team back in 1984. Now, a crop of modern, soon-to-be MLB stars would call Evansville home on their road to The Show. Quite the change-up from the independently run Otters, who had been around for nearly a decade.

“We would’ve done big things with Don Mattingly and Cal Ripken Jr. in Evansville,” Heller told the Courier & Press recently. “There’s no doubt about that.”

Except, it was too good to be true — or maybe it never should've been proposed in the first place. Not enough people supported a new stadium. And on March 31, 2003, with construction overrun pushing $3 million, Mayor Russ Lloyd Jr. declared: “This project is dead.”

What if the stymied stadium wasn’t axed? Could it have been a success? What would’ve happened to Bosse Field?

Let’s play hypotheticals.

Baseball: MLB considering hosting a game at Evansville's Bosse Field

Why the proposed minor-league baseball stadium fell through

Heller didn’t hear the news until the day after Lloyd made his decision. “Baseball stadium plan strikes out,” the cover of the Evansville Courier & Press read on April 1.

And, understandably, Heller thought it was an April Fools Day joke.

Heller owned the South Georgia Waves, the Class A affiliate for the Dodgers, and was looking for a new home. He hoped to move them from Albany, Georgia, promising to also put $12 million into the Evansville over a 20-year lease. Casino Aztar would’ve paid $10 million in riverboat money. Bonds would supply about $13 million more.

The original financing plans required no public funding. But as projected costs began to soar millions of dollars over budget, the mayor feared it would cause the city to raise property taxes — something he was unwilling to do.

Lloyd pulled the plug and it marked the downfall of his tenure as mayor. Later that year, he lost his re-election campaign by a 2-to-1 ratio to Democrat Jonathan Weinzapfel. Those who were for the ballpark felt betrayed; those against it already backed his opponent. Lloyd even received death threats over the stadium fiasco.

He declined to comment for this story, simply stating he prefers to look forward and “it was a big idea that didn’t work out.” It still cost the city $1.24 million, mostly for preliminary design work.

Heller later sold the Waves, though he currently owns three minor-league clubs. The franchise eventually became the Bowling Green Hot Rods, a Class A affiliate for the Tampa Bay Rays. They play an hour-and-half southeast of here in Bowling Green, Kentucky. Heller maintains that a stadium in Evansville would’ve boosted an undeveloped part of town, considering the site of home plate remains a strip club.

“If you say to people, ‘You have a choice at the gateway to our city: You can be next door to a pornographic bookstore or a thriving minor-league ballpark with a Dodgers affiliate.’ I think people would be much more inclined to choose the latter,” Heller said.

Clayton Kershaw would’ve led a flock of future MLB stars from Evansville to the World Series

Let's pretend, for a moment, that everything instead went according to plan.

Opening Day 2004 would’ve marked a new era for this baseball-rich market. Over the course of two decades, Heller estimates roughly 150 players from the Evansville franchise would’ve reached MLB.

By 2007, a rangy, 19-year-old lefty named Clayton Kershaw would’ve made a pit stop on his way to a Hall of Fame career. He would’ve joined the likes of Warren Spahn, Bert Blyleven and Mark “The Bird” Fidrych to pass through town.

The Dodgers won the 2020 World Series behind a stable of homegrown talent. That includes World Series MVP Corey Seager, a 2012 draft pick. Many other big-leaguers also would have worn an Evansville jersey between Joc Pederson, Matt Kemp, Walker Buehler and Gavin Lux. Plus, some local faces: Mattingly’s son Preston, a 2006 pick out of Central High School, and North graduate Cameron Decker, who LA drafted last summer.

Countless other well-known prospects would’ve been on opposing teams.

“We’re in the memory-making business,” Heller said. “I think that the opportunity to go down to the ballpark in Downtown Evansville to see the future Dodgers stars of tomorrow right there would’ve been special.”

History of pro baseball in Evansville: Hall of Famers, Triplets, Otters and more

Then again, most people don’t go to Otters games because of the on-field talent. Nor would many casual fans recognize those eventual big names at that stage of their careers.

Bill Bussing has owned the Otters since 2001 and still maintains a goal of providing affordable family fun. He never publicly criticized the prospect of a new ballpark, but he’s skeptical whether it would’ve made the splash some hoped.

“If you’re a kid — we don’t know who Clayton Kershaw is yet — and you see a player at the front gate who shakes your hand and gives you an autographed baseball, it really doesn’t make a difference who it is,” Bussing said. “It’s the experience of going to a ballgame.”

Even if new team wasn’t a hit, Bosse Field might have closed its doors

Since we are playing a Choose Your Own Adventure game, there are three ways a new team could have struck out even with the construction of a shiny stadium. After all, a vocal majority opposed this project from the onset.

■ Bye, bye Bosse: The new Class A franchise would’ve needed to average 4,000 fans to be profitable, according to a feasibility study conducted by “The Mayor’s Baseball Study Committee.” The group spearheaded this entire endeavor, first presenting its findings in October 2002.

Crowds that size would have easily pushed the Otters out of business. Bosse Field could have gone the way of Mesker Amphitheater: Closed and fallen into disrepair. Perhaps the Evansville Vanderburgh School Corp. would’ve kept up the maintenance for local high school teams to keep using it, but most of them have built their own fields and it might not have been viable without a pro team paying a lease.

Bosse Field’s aura is one of many reasons MLB officials are considering hosting a game at the park, as early as 2024. A shinier new alternative could've prevented that interest.

“I promise you if we’re playing in a Downtown stadium, (MLB) wouldn’t be talking to the mayor,” Bussing said.

■ Failure to launch: Triple-A baseball left town in the 1980s because people didn’t support it. Why would Single-A baseball work out this time around?

A new stadium would’ve hosted 66 games annually from April until September. In those early months, even in the big leagues, ballparks sit largely empty because of the weather and because kids are still in school. Plus, it would have been more expensive. At the time, Heller said a family of four could attend a game for $40; the Otters’ family pass cost $12.

That’s not to mention the affiliation. There was no guarantee local fans would become passionate about Dodgers prospects. Plenty of those opposed to the stadium might also have been reluctant to then attend, too.

“This is Cardinal Country or Cubs Country or Reds Country,” Bussing said. “It’s not Dodger County. I can name die-hard Dodgers fans on one hand. I do think who the parent club is has some impact on that.”

■ Sign of the times: Let’s wrap up with the most nihilistic approach.

Say the Otters folded, Bosse Field closed and affiliated ball wasn't making a lasting impact over these past two decades. In 2020, MLB axed 40 of its 162 affiliates from the minors — most of them either in rookie or short-season Class-A ball, but some as high as Double-A.

What if one of those would have been Evansville? The stadium would have been nearing the end of its original 20-year lease with the city by then. The Dodgers could've found an affiliate closer to home and maybe there wouldn't be another to take its place.

The grass isn't always greener, as they say.

“Who’s to say there will still be Class A baseball in a few more years?" Bussing said. “Almost every city of any size had an affiliated baseball team and that’s not the case anymore. Independent baseball is on the rise. That’s where the action is. It’s three hours of magic and then we go back to our regular jobs.”

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Why didn't the Dodgers put a minor league team in Evansville, Indiana?