Looking Back: A colder land there ne’er could be, Michigan

CHARLEVOIX — Last week, Looking Back reported on the near tragedy of the Albin Stover family when they tried to make it by horse-drawn apparatus from Norwood to Northport over an icebound Grand Traverse Bay. Even though the temperature was extremely low, the horse went through a patch of thin ice and drowned. They were lucky enough not to follow, but were able to continue seven miles on foot against steady bone chilling winds. By the time they reached the far shore, Mr. Stover’s hands were frozen to the point it was speculated he might have to have them amputated. The March 7, 1873 Sentinel advised its readers, however, that “We learn that the injuries to Mr. Stover from freezing his hands are not as bad as stated last week.”

Several previous Looking Backs have related the constant complaint of Sentinel editor Willard A. Smith that not a few subscribers were chronically late in paying their renewals for the paper. He informed them how chopped wood and potatoes would be accepted as legal tender, and this week maple sugar was added to the list. Also, Newman’s General Store was having a sale at which some slow moving merchandise was going at cost, for instance ice skates for 65 cents. Back then these were metal blades held on by straps.

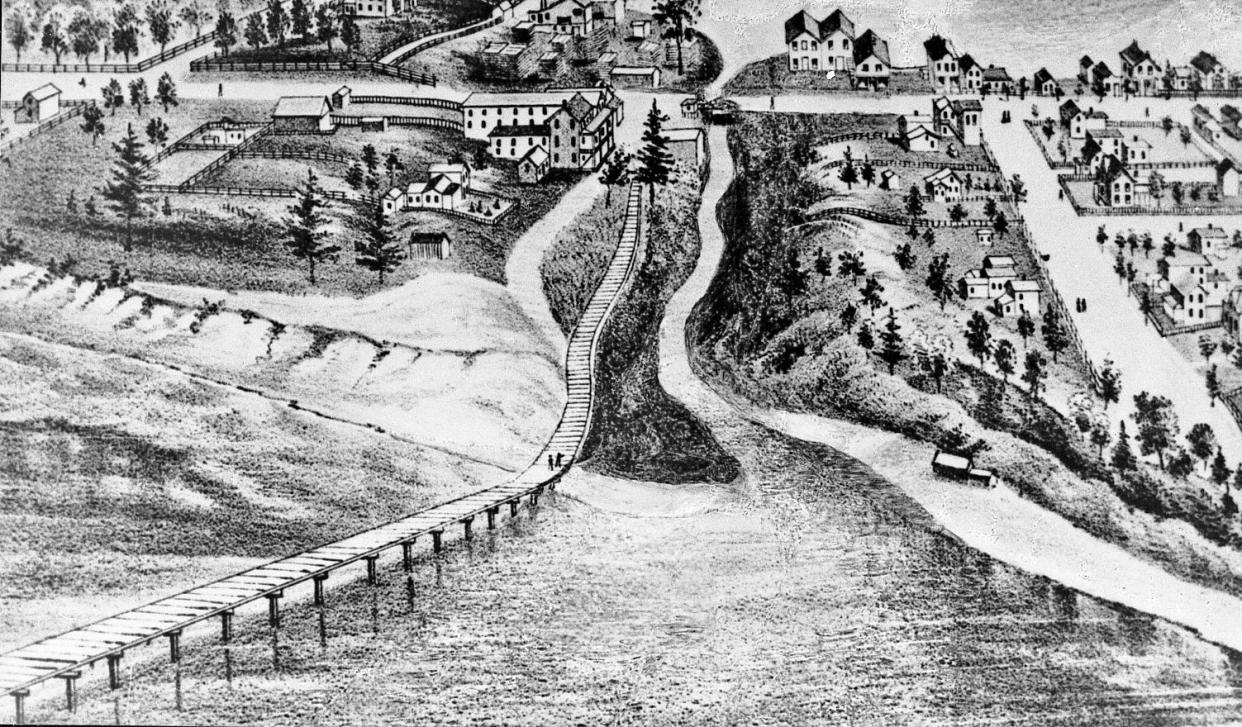

Richard Cooper, owner of the Fountain City House hotel on River Street, currently Pine River Lane going west from the Weathervane restaurant, announced that business was so good he had to eliminate his third floor ball room, Cooper’s Hall, to make way for eight more “sleeping apartments.” From a small building erected as a temporary boarding house for dock workers on Lake Michigan in 1864, to its conversion into a hotel in 1867 by Cooper, then the widening of Pine River creek into a channel in 1869 that opened up Round Lake to the world, Charlevoix’s first hostelry grew so fast that within three years of the channel opening it stood three stories tall. Two more large additions followed in 1877 and 1879. During June and July alone of 1883, 1,422 arrivals registered at the Fountain City House. By 1885, town-wide hotel registrations reached the 10,000 mark, and increased every year after that. Charlevoix was now firmly on the map, tourism had become a serious business, and there was no turning back.

Another bugaboo that Willard Smith often kvetched about was people who perpetually disparaged his editorial judgement. “Editing a newspaper is very much like raking the fire—everyone thinks he can perform the operation better than the man who holds the poker.” That was one of his milder views on the topic. And in that same newsy issue, Willard reported that the temperature, within three days, had gone from 3 below into the 50s above. Spring was peeping through.

One of the reasons the settlement of Pine River became finally known as Charlevoix in 1879, after years of a dual identity, is because of the confusion caused by the existence of other Michigan settlements called Pine River. For instance, Willard reported how we missed out on a crucial federal dredging of our four-year-old lower Pine River channel, a vital need to keep commerce on the move. These dredgings were the result of scheduled surveys as to what port needed how much attention and when.

“THE SURVEY.—It now appears that the ‘whereas’ of the failure to survey the mouth of Pine River last season, according to the provision of Congress, is that the War Department caused the survey of the mouth of Pine River, St. Clair county. Through the technical error of not more definitely describing the point, we are again temporarily defeated.” Note the word “again.” “The spirit of the Act provides for the survey of the mouth of Pine River, Charlevoix, county, Mich., and we have sufficient faith in Senator Ferry—under whose solicitation it was included in the Act—to know that he will cause a correction of the mistake.” By the mouth of Pine River, Willard is looking at the sand bars that could form across it, often just two feet deep, that impeded the advancement of larger vessels into Round Lake.

Fifty years later, the March 7, 1923 Charlevoix Courier printed an ode to winter, back then much more severe than winters are now, but even today we get equally impatient as they wear on. “FROZEN FEET AND A DOLEFUL BLEAT. Now that the worst is probably over, perhaps we may dare admit the truth by reprinting that anonymous lyric entitled ‘Michigan:’ Home of my heart, I sing to thee, Michigan, my Michigan;/A colder land there ne’er could be, Michigan, my Michigan;/Nine dreary months of snow and sleet, We limp around with frozen feet;/Yer derned old climate can’t be beat, Michigan, my Michigan.

“Your loyal sons will ne’er forget, Michigan, my Michigan;/This year’s the coldest winter yet, Michigan my Michigan;/Your cold winds howl around our knees, We poke the fire and sit and freeze—Oh what’s the use of B. V. D.’s, Michigan, my Michigan.”

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Looking Back: A colder land there ne’er could be, Michigan