Looking Back: Connecting lakes, creating opportunity

CHARLEVOIX — This is number three in a series, based upon an upcoming exhibit in July at the Charlevoix Historical Society’s Museum at Harsha House, “The Maritime History of Charlevoix, the City on Three Lakes.”

Last week, Looking Back examined the first large infrastructure that jumpstarted Charlevoix’s nascent economic development, the great 900-foot Fox and Rose dock in Lake Michigan. After it was up and running in 1865, the largest lake vessels of the time began to stop at the dock to take on wood fuel, the primary reason it was built. But that’s as far as they could get. Entry into Round Lake was limited only to small vessels. Even that was not an easy chore against a swift-running Lower Pine River littered with stones and fallen trees.

In the earliest days of the settlement itself called Pine River in the mid-1850s, a pathway was carved along the stream’s south bank so that boat owners could tow their vessels eastward, against the current, into the inner harbor. But entry into Lake Charlevoix that lay beyond was even more difficult, because the stream called Upper Pine River that ran from that lake into Round Lake was so shallow that larger boats had to be manipulated by much muscle power up its course. Small sailboats, flat-bottomed scows, rowboats and canoes were able to do it with lesser difficulty.

The Commodore Nutt, the first steam-powered vessel to part Lake Charlevoix’s waters, arrived in 1867, followed by the Minnie Warren two years later. Both tugs were put to work towing logs up Lake Charlevoix. They nudged the logs into Upper Pine River a few at a time, which were guided down into Round Lake, then taken over to the Edgewater Inn area to a small sawmill that processed their wood into large fuel pellets to be taken to the Lake Michigan dock by tramcar.

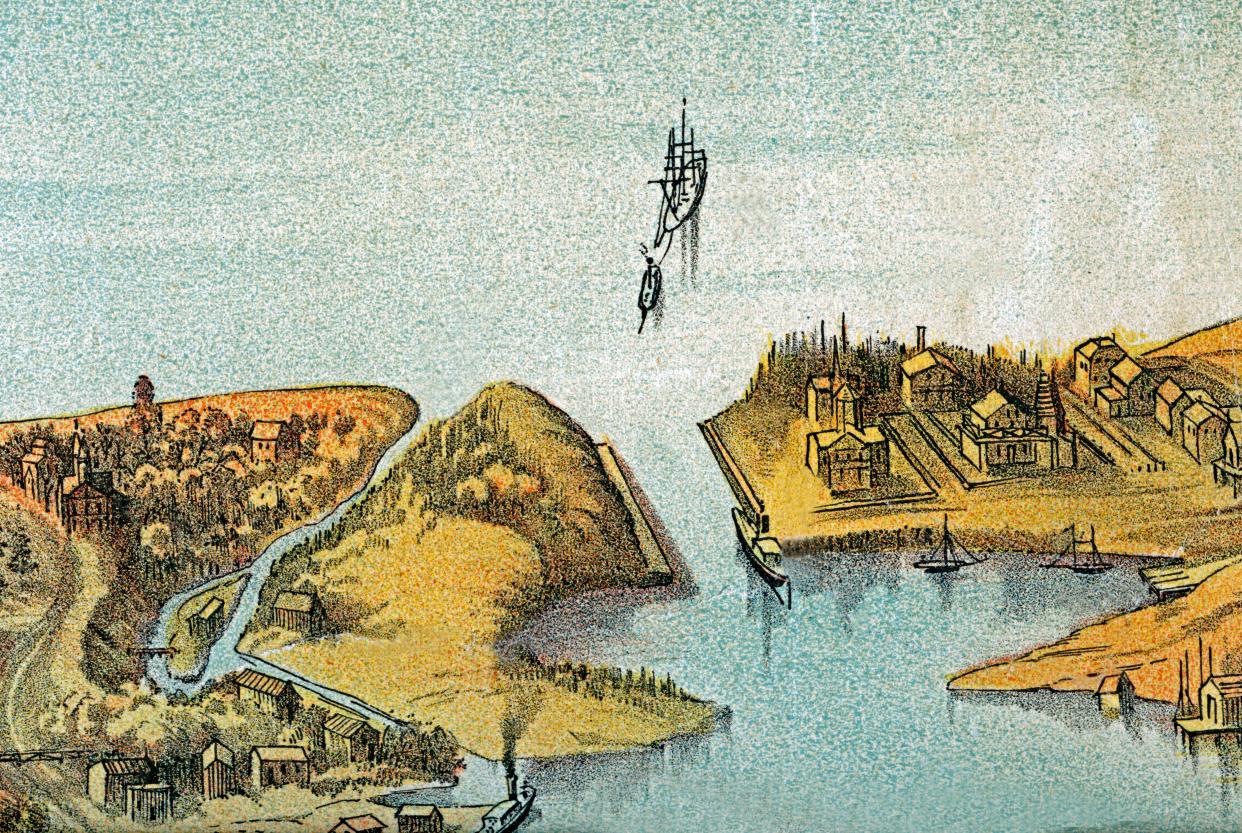

The city fathers began to realize how much better it would be if access could be provided between the inner and outer lakes. A few primitive attempts to cut a lower channel had failed, mainly due to little available money. So meetings were held, discussions ensued, and the determined Charlevoix Harbor and River Improvement Company was formed. A request to the federal government for assistance resulted in the arrival, in 1868, of Brevet Colonel J. B. Wheeler, Major of Engineers U. S. A. A survey map of Round Lake, and parts of the two streams, was drawn under his direction by Wm. J. Cosgrain, complete with depth sounding indicators all over the water.

According to the Traverse Region 1884 book, Wheeler concluded that “there were insurmountable obstacles in the way of making a harbor, and that a harbor of refuge was not necessary at this point, owing to the proximity to other good harbors. His conclusions were based upon the fact that . . . the Company had [tried to cut through the obstructing (Lake Michigan) sandbar], and owing to lack of funds had discontinued the work.”

Wheeler estimated $5,000 to $10,000 to “cut a canal between Round Lake and Pine Lake (Lake Charlevoix)”, and “an immense amount of money to open a new entrance into Lake Michigan near the mouth of Pine River."

Someone else, or perhaps himself, had taken Wheeler’s findings and come up with an estimate of $200,000 for the lower channel alone, equivalent to over $4 million today. The reason? It was discovered later that when Wheeler’s recommendation came up for review, the request of another Pine River, located on Lake Huron, was asking for help also. The requests got mistakenly switched. So a port that had a shallow entry river running over thick bedrock was discussed, rather than a port that had a swift little stream impeded only by some rocks and fallen trees, and a rather sandy bottom. This was not the first time that Pine River on Lake Michigan would get mixed up with its counterpart across the state, and important work that should have been done here wasn’t.

When the erroneous $200,000 figure came back, the never-take-no-for-an-answer Company snorted “Balderdash! We’ll do it ourselves.” It solicited subscription funds for the project, and when a few hundred dollars were in the bank, set to work on the upper cut first, in July of 1869. About a hundred men plus horses were gathered from around Lake Charlevoix to begin cutting through the 240-foot neck of a peninsula that stretched from today’s Belvedere Club land northward to Upper Pine River. Trees were felled, underbrush removed, land leveled, and a crude, straight ditch was etched into the cleared ground.

The finishing touch was provided by the Minnie Warren, whose stern was backed against the Lake Charlevoix end of the ditch. Its propeller was turned on full blast, dirt and sand began to fly, the Minnie Warren was guided backward inch by inch until it broke through into Round Lake, and the first substantial waters of Lake Charlevoix began to flow westward. It was claimed that, at the time, Lake Charlevoix was two feet higher than Round Lake, which itself was two feet higher than Lake Michigan. However, there was never any reportage of a swift dropping of the waters from one lake to the other.

The first step of this ambitious project had succeeded by the end of August. It was time to relax a bit, catch their breath, then the Charlevoix Harbor and River Company set to work on phase two in September, the cutting of the Lower Channel to Lake Michigan. The settlement of Pine River and the county of Charlevoix were within weeks of setting off an economic explosion the likes of which were beyond their beyond their wildest expectations.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Looking Back: Connecting lakes, creating opportunity