Looking Back: Frozen foragers, fires and free time

CHARLEVOIX — One hundred fifty years ago, the March 1, 1873 Charlevoix Sentinel ran an item from the Cheboygan Independent newspaper, stating that “there are 25 lumber camps on the Cheboygan river and its tributaries. They average 25 men in each camp. There will be cut, hauled and delivered about 40,000,000 feet (of lumber) this winter.”

The mind boggles, and lumbering had about four more decades to go.

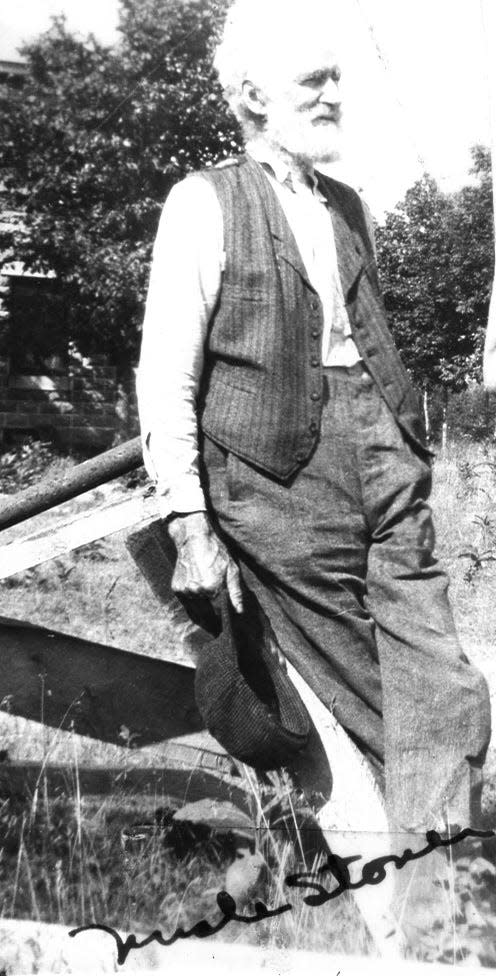

In the same issue, editor Willard Smith reported on the terrifying ordeal of a local family who tried to cross the lake ice to get to Northport on the tip of the Leelanau Peninsula. They were from the pioneering Stover family, after whom Stover Road and Stover Creek through Brookside cemetery to Lake Charlevoix are named.

“BADLY FROZEN. We learn the following from a gentleman who came from Norwood on Thursday: Albin Stover, of this Township (Charlevoix), with his wife and three children, left Norwood on Sunday morning to cross the Bay to Northport in a one-horse conveyance. When about half way across, in attempting to cross a crack in the ice, the horse broke through and was drowned. They were then forced to walk the balance of the way, assisting the children, who were undoubtedly benumbed, and facing the keen wind of that extremely cold morning. By the aid of Providence they walked that seven miles with the weather 24 degrees below zero, but when they reached Northport Mr. Stover’s hands were so badly frozen that it is thought amputation will be necessary. Mrs. Stover’s feet were frozen, and the children were more or less injured. The horse belonged to Hugh Miller, of this Township.”

Perhaps near future issues of the Sentinel will report an update on all their conditions. Mr. Stover had built a grist mill on Stover Creek.

Fifty years later, both the Charlevoix Sentinel and Charlevoix Courier devoted extensive front page coverage to two devastating fires that had destroyed a section of downtown Petoskey on Feb. 15, 1923. The first broke out just after 2 a.m. on the south side of Mitchell Street at Howard, destroying buildings that housed not only businesses on the ground floor but also apartments on the two floors above. Some tenants were forced to jump from windows into snowbanks below, sustaining injuries ranging from cuts and bruises to life-threatening, taking with them only the clothes on their backs, their other possessions a total loss.

The second fire, in a neighboring building on Howard Street, was thought to have been a result of the first one, probably from smoldering debris carried onto its roof by the strong wind blowing. This fire, not quite as extensive, broke out six hours later, and partially damaged another building next to it. The initial conflagration was so intense that walls buckled and fell outward across the railroad tracks that ran through downtown Petoskey. In all, around 50 people were displaced. Initial estimated damage was $250,000, which today would be $4,374,000.

Subscribe:Check out our offers and read the local news that matters to you

Charlevoix has been reminded in recent years just how vulnerable our downtown buildings can be, with the total loss of the Johan’s pastry and coffee shop plus the art gallery next door, then severe damage to the Van Pelt/ Cherry Republic building, and the fire/water/smoke damage that swept through all the stores at Oleson’s Plaza.

Speaking of Cherry Republic, both newspapers reported that work was about to begin on the transfer of Charlevoix’s telephone exchange from the top floor of the building that now houses That French Place, the crepes shop, across the street to the Levinson building’s second floor. Meyer Levinson owned a dry goods emporium that would later house a cherry products emporium. That French Place, in turn, occupies the oldest surviving wood commercial building on Bridge Street, built 1875.

The Feb. 28, 1923 Courier also reported on the decision as to whether Charlevoix should go on daylight savings time. Yes, you are reading right. Back then, municipalities could decide for themselves whether to make the switch, to some a pesky, unnecessary irritant.

“A petition was presented to the city council at their meeting Monday evening last, signed by a number of businessmen and others, favoring the establishment of fast, or eastern time, during the coming season. The council has agreed to place this proposition on a separate ballot to be voted on at the spring primary. Although there may be some little annoyance experienced by those whose work is more or less intimately concerned with the railroad train schedule, as in the case of the post office, draymen (freight haulers), and bus-drivers, the majority of the town’s population will, we believe, be benefited greatly by the change,

“While it necessitates a little early rising, on the other hand, it means an hour of extra leisure on the other end of the day. For instance—if your alarm clock is set for five-thirty a.m. fast time, it will be necessary to roll out of the feathers at the witching hour of four-thirty sun time. However, this will not be hard to accomplish as Old Sol will be up and doing and roosters crowing by the time your unslippered feet hit the floor. At seven o’clock the sun time stores will be open; at eleven you will eat the midday meal and at 4:30 p.m. you will lock the safe, kick the office cat down the back stairs and sally forth into the warm sunshine with nothing to do until tomorrow. This arrangement should be eminently satisfactory to everybody.” Maybe.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Looking Back: Frozen foragers, fires and free time