Looking for a few good rangers: National Park Service is diversifying its ranks

With women filling only about one in 10 law enforcement ranger positions, the National Park Service is adopting a hiring program to diversify the force responsible for keeping people safe in some of the nation's most treasured public spaces.

Law enforcement rangers serve as police in the more than 400 parks, monuments and other places the park service protects throughout the country and its territories. In contrast to other rangers who typically conduct educational programs for visitors, they make arrests and conduct search-and-rescue operations. And, like in many other police forces, the job has traditionally been filled by men.

While the park service has been making progress in recent years toward improving the number of women in its workforce generally — only about 20% of jobs were held by women in 1975, while nearly 40% were in 2020 — that trend has not held true for the parks' cops.

The new initiative is hoping to increase the female share of the force to at least 30%, said park service spokesperson Cynthia Hernandez.

It aims to provide more opportunities for more people by streamlining the hiring process and easing the financial burden it previously put on candidates. Janet Kelleher, the hiring and recruitment manager for the park service's Law Enforcement, Security, and Emergency Services program, said that previously many who wanted to do the job could pay $10,000, depending on the program they pursued, to put themselves through a variety of academies and other trainings. They then were able to apply for temporary positions at parks, with no guarantee they would be hired permanently.

"While we have hired some phenomenal rangers through that program, we missed out on a lot of talent because of those barriers," Kelleher said. "Now we're hearing people say they've wanted to do this job for 15 years but couldn't because they couldn't afford it or couldn't leave their family unsupported."

‘You don’t have to fit a mold’

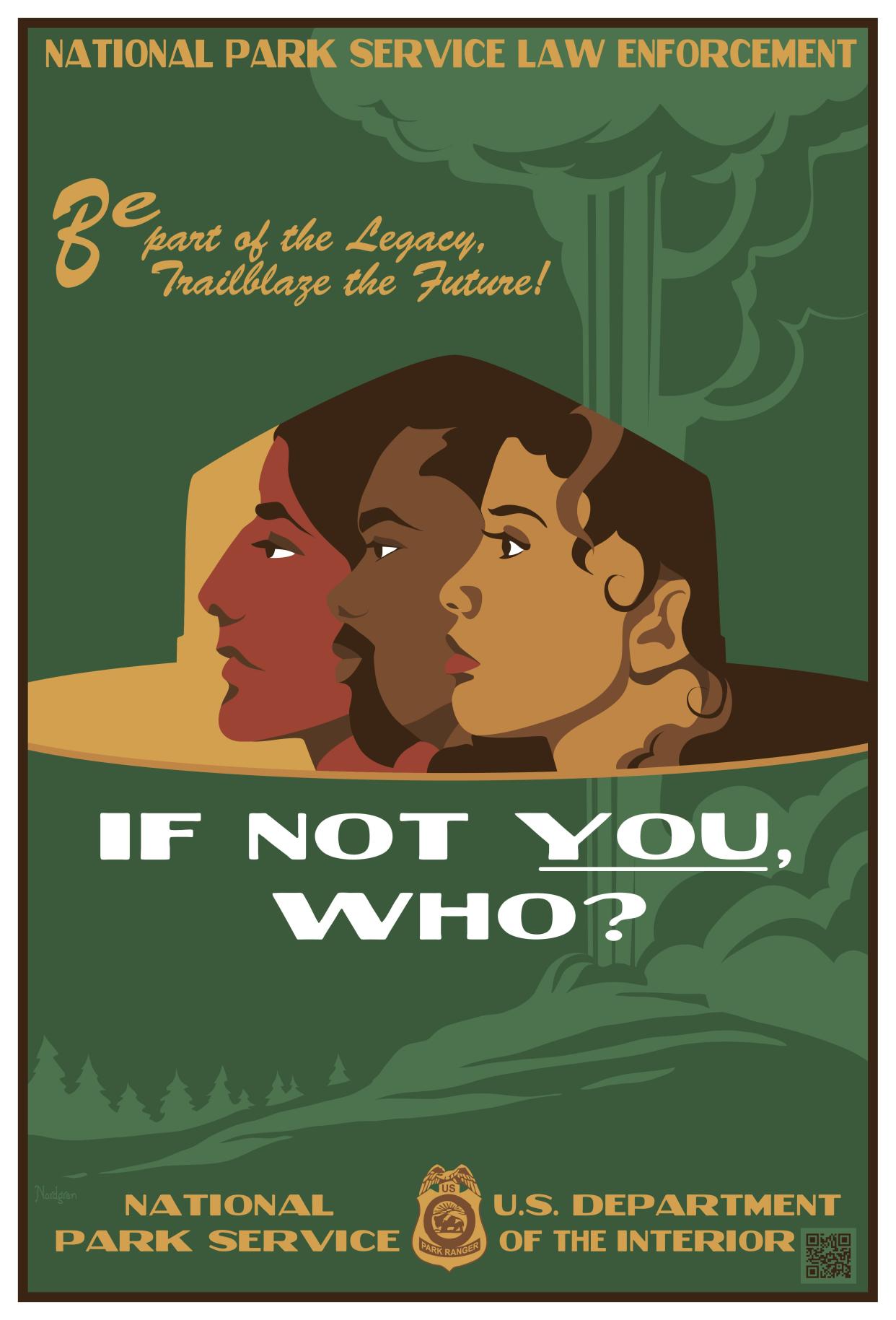

About two years ago, the park service introduced the "Direct-to-FLETC" program, which fast tracks hires directly to the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center at no cost, considerably cutting the time and resources to place candidates in the field and in permanent jobs in the parks. The program was first launched as a pilot in 2021 with recruitment posters reflecting the diversity of candidates the park service was hoping to draw.

"We are also working to increase recruitment from other underrepresented groups, including racial and ethnic diversity and LGBTQ+ candidates," Hernandez wrote in an email.

And that work is paying off.

Emily Hassell was a member of the pilot program's first class. She was working in a job at Joshua Tree National Park when she was first introduced to law enforcement ranger work.

"I'd always been interested in law enforcement, but I was really drawn to how diverse and hands-on their job was," Hassell said.

When she inquired about her interest, she was told how difficult it was to put yourself through training and work seasonal jobs for years. But when she heard about the pilot program she jumped at it.

"It seemed about half of my FLETC class were female," she said. "I was being trained with people who had been in the military, who had resource backgrounds and people right out of school."

She's been a ranger for about a year and a half now, currently working at Grand Canyon National Park. She was the only woman in her district when placed, she said, but she's seeing that change with several female colleagues currently.

"People shouldn't shy away from the park service because they think they don't belong," she said. "They might think: 'I'm not macho law enforcement,' or 'I don't have experience doing this.' You don't have to fit a mold. You can be yourself."

Madison Reika is a law enforcement ranger in Washington's Mount Rainier National Park, and a supporter of the new program. She first joined the park service working with the Youth Conservation Corps in Yellowstone National Park teaching children backpacking and other outdoor skills.

"I remember one time telling someone they couldn't walk on the travertine," Reika said. "They responded with something like, 'You're just a silly girl.' No, I'm protecting the park's resources."

Experiences like that opened her eyes, she said, to the broad range of jobs in the park service and eventually motivated her to save for two years to put herself through an academy. Paying her own way was tough, she said, with times she and others struggled to afford food and housing. After she worked temporary positions to eventually get a permanent job, she was sent to the FLETC program paid for by the service.

"I learned a lot more when I didn't have to worry about if I had enough food for the week," she said.

Rigorous training, rewarding work

Kelleher emphasized that the park service's current law enforcement ranger force is made up almost entirely of people who were hired through the self-funded process. While adding that the agency appreciates the sacrifices they were willing to make to get the job, she said the new program should make it easier for more people to get involved.

"We don’t want to undervalue the work rangers like Madison put in. I did that myself," said Kelleher, who became a law enforcement ranger in 2012. "But is that what we should be asking people to do? We should be recruiting the most talented people and giving them the training to do this."

And while the dangers of federal law enforcement aren't for everyone, Kelleher said, many might not realize how much they'd like this job.

"We hire folks who already have some law enforcement or emergency services experience," she said. "We also hire people completely new to this."

The program starts with about three months of law enforcement and land management training at FLETC. Then the candidate is placed for 11 weeks of training at one of the national parks.

"It's rigorous," Kelleher said. "It involves physically and academically challenging work. It covers not only things like firearms and arrest techniques. It's Constitutional law. It’s emergency driving. They’re not only learning about the Fourth Amendment, they're learning about the Archaeological Resources Protection Act."

It's inherently dangerous work enforcing the law in both the most heavily visited and most remote parks in the system. Reika described field training as being partnered with a veteran ranger teaching the recruit the basics in a "crawl, walk, run" way. Showing them first how to conduct, for example, a traffic stop, then eventually acting only as backup as they manage situations on their own.

"In this job I've done so many things I never expected doing," Reika said. "Everyone thinks of parks as these magical places. And they are. But everything that happens in the real world happens here. "

Hassell echoed the thought, saying, "Sometimes we joke: 'Criminals go on vacation, too.' We see all kinds of things and there's no limit to the kinds of calls we get."

Hassell said that those encounters can be difficult, like an emergency call she responded to where a person needed CPR. Despite the best effort of her and her colleagues, the person died. She said she later responded to a call of a person who was impaired and ultimately detained.

"I ended up spending a couple of hours with them and they told me they remembered me from the CPR call," she said. "They thanked us for trying so hard."

From DUI stops to intervening in domestic disputes, investigating vandalism and archaeological theft, Reika similarly said she's no stranger to distress. But she said she doesn't feel like she has to face these challenges alone. When the pressures of the job mount, she said she knows she can rely on her colleagues — many of whom she met while being trained for the job.

"If I have a hard day, I know I can call a ranger I know in North Carolina and talk about it," Reika said. "If I had a hard call, I can reach out to someone I know who has been through something similar working in Utah. Even if we don't work in the same park, it's a great network of support, and it only keeps growing."

Interested candidates can apply at USAJobs.gov, a federal job listing site, where two listings were posted Monday, each with a limit of 550 applicants, one for current federal employees and the other open to any citizen. The postings will expire May 22 or when the application cap has been met.

Desert Sun reporter Christopher Damien covers public safety and the criminal justice system. He can be reached at christopher.damien@desertsun.com or follow him at @chris_a_damien.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: National Park Service is diversifying ranger ranks