Looking at Washington, D.C.'s Lincoln Memorial, through the eyes of a sculptor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

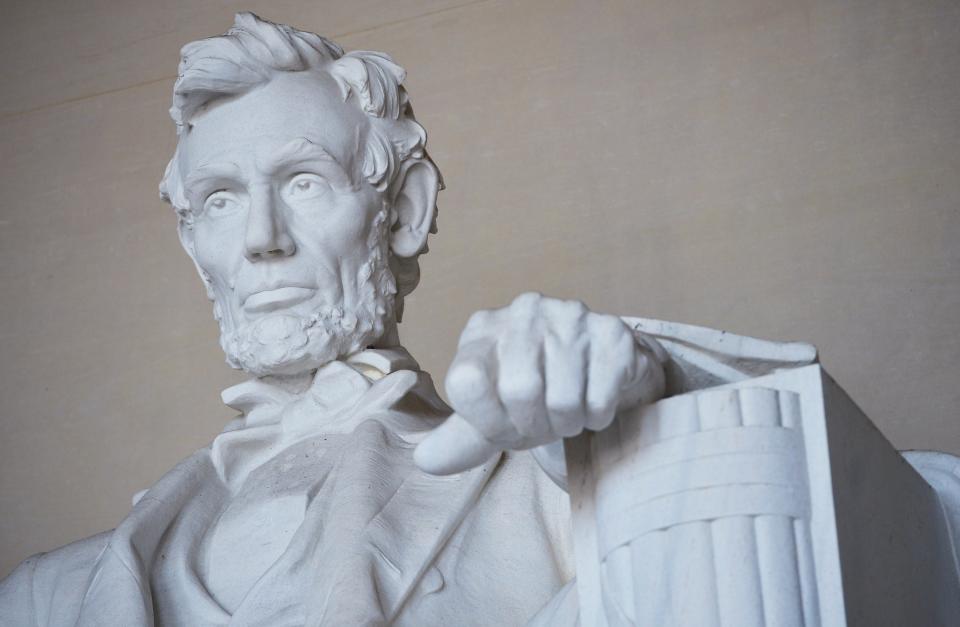

The Lincoln Memorial is a shrine, a symbol, a portrait of a soul.

For sculptor Sabin Howard, it's one other thing as well. It's a challenge.

"This is the standard for national memorials," said Howard, who has the daunting task of coming up with a monument worthy to be in its shadow.

For three years, in a cavernous studio in Englewood, New Jersey, Howard and a handful of assistants have been working on "A Soldier's Journey," Washington's newest monument.

More:How do we commemorate war heroes in a country in an era that is disconnected from war?

This epic bronze tableau, 58 feet long and 10 feet high, with 38 figures of doughboys and nurses, will be America's World War I memorial when it is unveiled in May 2024 (fates allowing) at Pershing Park.

It will be, by some accounts, the largest freestanding bronze relief in the western hemisphere. And architect Joe Weishaar chose Howard for the project specifically because he wanted someone like Daniel Chester French — the sculptor who created the Lincoln of the Memorial.

"I feel very responsible," Howard said "I feel the gravitas of the project."

One odd way that's manifested itself is in exercise. Howard was always fit, always an avid biker — 10 or 20 miles a day was typical. But now it's more. It's almost as if he's remaking himself to the heroic proportions of the figures he's sculpting.

"Now I'm biking 140 miles a week," he said. "Because I have to be the man who can pull this forward. It's like pulling a huge train forward to the station. I'm doing this because it's really necessary that our country has this kind of sacredness in a public space. That's my responsibility."

The 19-foot marble Lincoln, created by French — it celebrates its 100th birthday this year — is often in Howard's thoughts. It's an inspiration. Also, in a real sense, what he's up against.

Lincoln Memorial: The monument to measure by

"I feel connected to it," he said. "I feed off of that to make something that is epic. Knowing that I'm doing something that is so sacred for so many people just drives me."

What Howard, born in New York in 1963 and reared in Italy, and the New Hampshire born French (1850-1931) have in common is that they were both schooled in the classical, heroic, figurative tradition — something that's been out of fashion for nearly 100 years. Abstract art has been the vogue since the 1930s.

But people, when they see a public monument, still expect to see something they recognize. And they also expect to be uplifted — something else that's not in the wheelhouse of most contemporary artists.

"The contemporary art being peddled in art shows and galleries is about irony," Howard said. "This is the opposite of irony. It's about what we can be. It's about our potential as people, and as a country."

So why is French's Lincoln so memorable? Howard has a few thoughts.

More:In war and peace, these armories in New Jersey are civic treasures

More:Paterson Underground Railroad site gets a prestigious recognition from the Park Service

The heroic size is obviously a part of it. Lincoln looms over the spectator. Also the way that French has captured, and accentuated, certain features, in order to bring out Lincoln's character.

"You see the guy's face, the heaviness of it," Howard said. "And it was sculpted to make a high contrast in spots that will draw out the viewer's emotional response to the sculpture. The brow of Lincoln was heavy, but obviously it was not that heavy."

French insists on the weight bearing down on the man — the weight of awful responsibility, in guiding the nation through its darkest hour. "It extends to the whole pose," Howard said. "There's this sense of weight on the shoulders. He's not erect. It's almost like he's slumped in the chair. And the chair is huge too. It pulls him down. You don't think he's getting up."

Sculpture captures a moment in time

Then, too, there are certain paradoxes, contradictions, in the very pose of Lincoln. One hand is open — receptivity, generosity — while the other is closed. "It's the close fist of the ruler, who rules with an iron fist," Howard said. "The fist is closed because he had to have a stubbornness to proceed." One foot is firmly planted, while the other looks like it's about to step off.

"A sculpture that's living, breathing, is a static object, but is has to tell a story of time," Howard said. "It's about a frozen moment."

But what gives the Lincoln Memorial its ultimate power — even a kind of sublime pathos — is context of the statue within the space.

The building, designed by architect Henry Bacon, is patterned after a Greek temple. It is a shrine to a god. In many ways, Abraham Lincoln is about as godlike as humans get.

But Lincoln, at the end of the day, was not a god. He was a man — who was called on to do the work of a god. Which is more, ultimately, than any human being can bear.

Hence the weary, slumping figure on the throne.

"Not only the sculpture, but the space that it occupies, and the play of light within that space, creates this power and grace and elevation of the human consciousness," Howard said. "That's what happens to me. I get elevated in a space like that. I have a sense of pride in being human."

Jim Beckerman is an entertainment and culture reporter for NorthJersey.com. For unlimited access to his insightful reports about how you spend your leisure time, please subscribe or activate your digital account today.

Email: beckerman@northjersey.com

Twitter: @jimbeckerman1

This article originally appeared on NorthJersey.com: Sabin Howard creating national monument dedicated to World War I