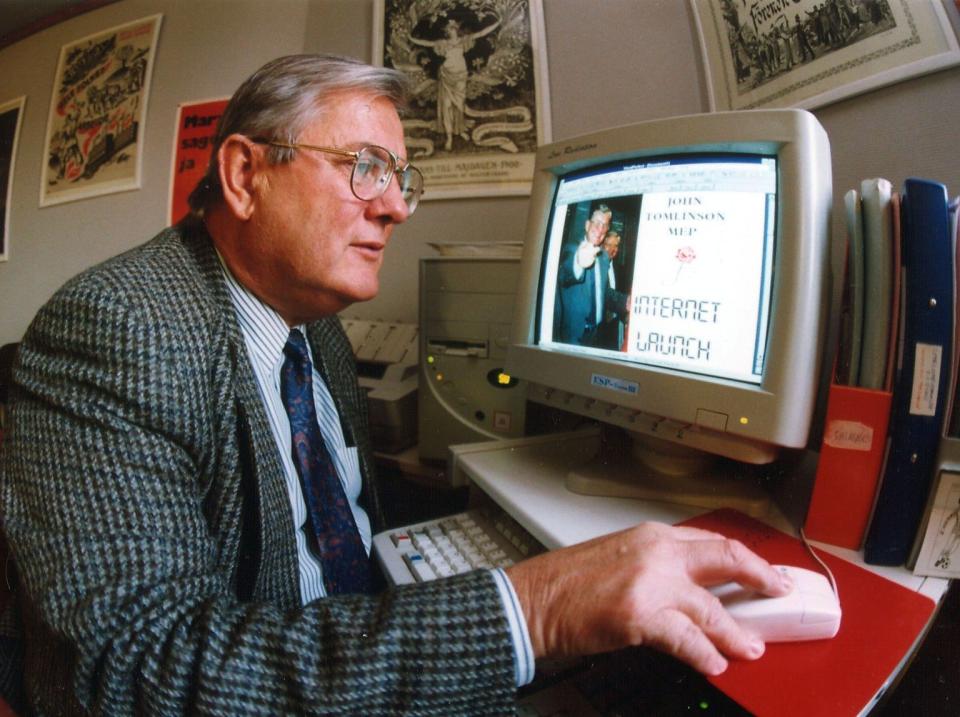

Lord Tomlinson, pro-European Labour moderate who was Harold Wilson’s final PPS – obituary

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Lord Tomlinson, who has died aged 84, was a moderate Labour MP and Foreign Office minister, then an MEP and deputy Labour leader at Strasbourg; he complained in 1994 of the British government’s “visceral dislike” for the European Parliament.

A member of Labour’s Manifesto Group and a leading figure in the Co-Operative Party, John Tomlinson was, as a new MP in 1974, accused of being one of an ultra-loyalist clique plying Harold Wilson with soft questions. For Wilson’s final months as prime minister, Tomlinson was his PPS.

John Edward Tomlinson was born in London on August 1 1939, the son of Frederick Tomlinson, a headmaster, and his wife Doris. He was educated at Westminster City School and the Co-Operative College, Loughborough; he later studied health services management at Brunel University, and in 1982 was awarded an MA in Industrial Relations from the University of Warwick.

Tomlinson began his working life in 1961, as secretary of Sheffield’s Co-Operative Party. In 1964 he was elected the city’s youngest councillor. In 1968 he joined the Amalgamated Union of Engineering Workers as its head of research, then from 1970 he lectured in industrial relations.

Tomlinson fought his first seat – Bridlington – in 1966. Having sat out the 1970 election, he was selected afterwards for the bellwether Meriden constituency – then Britain’s largest, with more than 100,000 voters. The Conservative Keith Speed had won the seat from Labour at a by-election in 1968.

When Edward Heath called the snap “who governs Britain?” election in February 1974 with the miners on strike, Tomlinson defeated Speed by 4,485 votes. That October he doubled his majority against a fresh opponent, Speed having taken over Bill Deedes’s seat at Ashford.

Tomlinson’s immediate priority was to save the threatened Triumph motorcycle works at Meriden, which the unions were trying to keep open as a workers’ co-operative. Tony Benn, Industry Secretary in Wilson’s incoming administration, put in government money, encouraged by Tomlinson with his Co-op background.

When Michael Heseltine accused Benn of pressuring the workers into agreeing to the co-operative by offering funds, Tomlinson retorted that his constituents were fighting 24/7 for the right to work, and unless funding were made available, jobs across the West Midlands would be lost.

The venture developed new 750cc models, primarily for the American market, but was eventually brought down in 1983 by the strength of the pound.

In December 1975, Tomlinson became Wilson’s PPS. Weeks later, in a late-night conversation at Number 10, he talked Bob Mellish out of resigning as chief whip after Labour MPs had defied him and inflicted a defeat on the government.

Wilson’s retirement in March 1976 did not leave Tomlinson jobless. Even before James Callaghan was elected to succeed Wilson, he was appointed an extra Parliamentary Under-Secretary at the FCO in advance of Britain’s first presidency of the EEC and the 1977 Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ meeting at Gleneagles. He would serve under two further foreign secretaries: Anthony Crosland and David Owen.

That May, he was hauled back with Roy Hattersley (his Minister of State) from an EEC ministerial meeting in Brussels to vote at Westminster, after the Conservatives refused to allow pairing. The meeting was on whether MEPs should be directly elected, and how many seats each member state should have, and until the issue was settled, this took up much of Tomlinson’s time.

In June 1977 he came under fire at the European Parliament after indicating that Britain was blocking funding for an atomic research centre in Italy until the Joint European Torus, the world’s largest magnetically confined plasma physics experiment, was awarded to Culham in Oxfordshire. It opened there in 1984.

Back at Westminster, Conservative MPs were furious when Tomlinson rebuked their colleague Victor Goodhew for describing the no man’s land between East and West Germany as a “death strip”; he told the House such words were “unhelpful to our relations with Russia.”

Early in 1977, he gained an additional ministerial brief, assisting the Left-winger Judith Hart at Overseas Development.

At the 1979 election that brought Margaret Thatcher to power, Tomlinson lost Meriden to the Conservative Iain Mills by 4,127 votes. He became senior lecturer in industrial relations and management, and later Head of Social Studies, at Solihull College of Technology.

In 1981 he published Left, Right: The march of political extremism in Britain, cataloguing the factions posing a threat to a liberal society. It included a claim that the year before, the KGB had sent one of its agents to inflitrate the Militant Tendency to shield it from “complete and damaging exposure” – this despite Militant being an openly Trotskyist organisation. Tomlinson also flagged up that the National Front was trying to infiltrate several trade unions.

In 1983 he contested the new seat of North Warwickshire, losing to Francis Maude by 2,585 votes. Then, a year later, he was elected MEP for Birmingham West.

At Strasbourg he became whip to the multinational Socialist group, over objections from the Labour group leader Alf Lomas, who customarily voted with the French communists. Tomlinson assured him he would be pressing members to attend, not telling them how to vote.

When, in 1987, Lomas was ousted, Tomlinson – one of the strongest pro-Europeans in the group – became deputy leader.

He spoke mainly on the cost to the taxpayer of food surpluses and fraud on the agriculture budgets, which he reckoned cost £5 billion a year. In 1993 he called on Ireland’s Agriculture Commissioner Ray McSharry to resign for having used his influence to protect Larry Goodman, head of the collapsed meat empire Goodman international, from its Dutch creditors.

As Labour’s spokesman on budgetary control, Tomlinson urged the European Parliament to save £30 million a year by sitting only in Brussels. He was furious when Air France offered British and Irish MEPs cheap fares as an inducement to continue sitting at Strasbourg.

In 1998 – the year before he left the Parliament – Tomlinson was created a life peer. In the Lords he served on the EU Select Committee, then chaired the Education Committee, and in 2002-03 was peers’ representative on the Convention devising a constitution for the EU. From 2004 he was a member of the Council of Europe and Western European Union.

In the wake of the Brexit referendum of 2016, he doggedly pressed Theresa May’s government for examples of progress in negotiating Britain’s withdrawal.

Tomlinson was at various times president of the Industry and Parliament Trust and the British Fluoridation Society, chairman of the Association of Independent Higher Education Providers, and a board member of Anglia Ruskin University and the Association of Business Executives.

When political duties permited, he and his wife lived at Elche in south-eastern Spain.

John Tomlinson married Marianne Somar in 1963. The marriage ended in divorce and in 1996 he married, secondly, Paulette Fuller.

Lord Tomlinson, born August 1 1939, died January 20 2024