‘I lost everything’: Black women get evicted more than anyone else. A looming eviction crisis will make it worse

AUBURN, Wash. – The green-sided house with the manicured lawn and juniper trees was more than a home to Nicole Chambers. It was proof she was a good woman, a good nurse, a good mom.

The eviction order she found cruelly silent on the dark green laminate countertop signaled she was about to lose the life she had worked so hard to build. Her sons texted her a photo of it when they found it taped to the red storm door that afternoon, but a part of her didn't want to believe it was true.

The hair on her neck stood up. Her feet were heavy on the wood floor. Her mouth was dry.

How could everything unravel so quickly, she thought.

Chambers' troubles began when she lost her nursing contract several weeks earlier, days before rent was due. A week later, Chambers asked her landlords for four more days to pay the rent.

She felt it was a fair request. The 44-year-old nursing assistant said she had paid her $2,490 monthly rent for four years without incident. She always took care of the house, putting any extra cash toward refreshing the paint or decorating. And her landlords knew how hard she had been working in COVID-19 wards treating intensive care patients up and down the Pacific Northwest.

But the letter in her hand stated she had 60 days to find a new place.

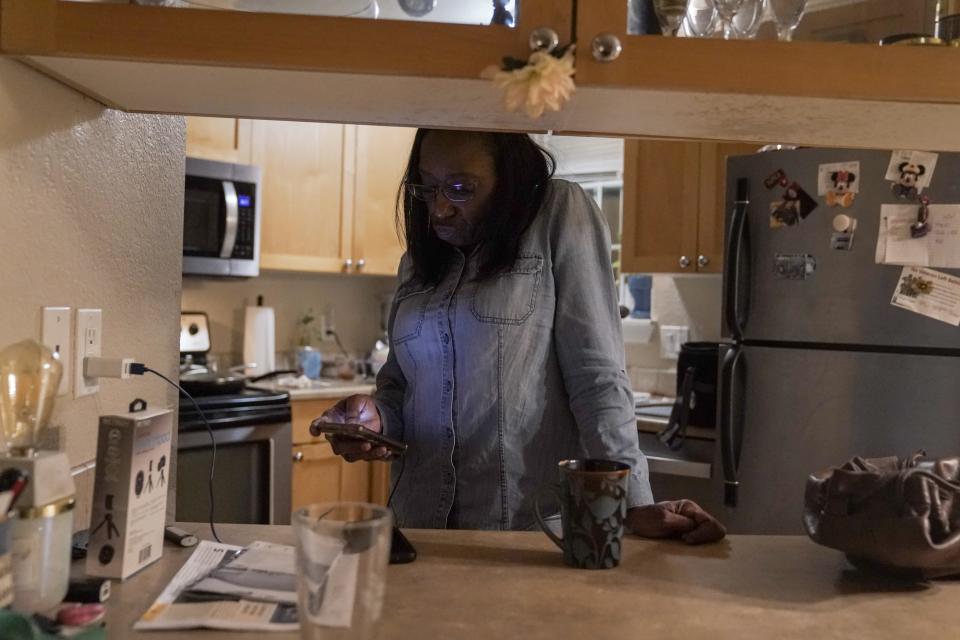

Several months later, the mother of three was living in the only apartment she was able to find with a fresh eviction on her record in north Seattle– it had no heat, no hot water in one of the bathrooms and no yard.

“I worked all my life, I have raised my kids alone, with no help and no child support, and now I have lost everything," Chambers said.

Chambers is far from the only Black woman whose life was upended after a landlord quickly pursued eviction. Black women are more likely than any other group to be evicted, according to a USA TODAY analysis of four years of local and national housing records and data from the University of California, Berkeley. Black women renters get filed against at twice the rate of white women renters nationwide. King County in Washington state has one of the highest eviction filing rates for Black women: Landlords file against Black women at five times the rate of white renters, in some cases over less than $10 in back rent.

For Black women like Chambers, an illness, car trouble, noisy children, hours cut at work or losing a job altogether could easily become grounds for eviction. Experts warn that fading pandemic protections may cause an avalanche of evictions in the coming months – and it’s highly likely Black women will once again suffer the most.

“It’s always been the case that evictions turn families’ lives upside down and make it even harder for families to find safe, stable homes in the future. These devastating effects fall disproportionately on Black and brown women and children,” said Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio, chairman of the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs.

Other findings of the USA TODAY investigation include:

In King County, Black women accounted for 16% of evictions while making up only 5% of the renter population.

Eviction proceedings are mostly formalities – even if a tenant owes rent and can come up with the money. Hearings often last minutes, and tenants are rarely given relief. It takes three weeks on average to get evicted in Washington state.

Among the top evictors in King County were corporate landlords who received subsidies and tax breaks for affordable housing.

Many tenants who receive eviction notices abandon their homes without challenging the eviction, often because they don’t know how to do so. When they don't respond or show up to court, this leads to what is called a default judgment in favor of the landlord, meaning tenants have days to vacate the property. Of the King County filings reviewed by USA TODAY, 44% resulted in a default judgment.

Black women’s vulnerability to eviction starts long before they sign a lease.

Black women are more likely to be single parents and listed as leaseholders. Black women have the highest probability of being given nuisance citations from the police, which can result in eviction. They earn on average less than other demographics. These factors are driven in large part by structural racism. Many studies concluded that Black women are judged more harshly in school, the workplace and the court system.

The result is generations of Black women struggling to keep roofs over their heads – falling further behind in the seismic wealth gap and being put at higher risk of ending up homeless, in prison or dead. Women and children experiencing housing insecurity and homelessness are more prone to adverse health problems, including maternal mortality, hypertension, arthritis, mental illness, tuberculosis, substance abuse, victimization and unsafe sexual practices, as well as criminal activity and barriers to education and employment.

"This kind of disparity doesn’t happen by chance," said Diane Yentel, CEO and president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition in Washington, D.C.

Graphic novel: An eviction crisis for Black women

Imagine you missed a rent payment. Now, you could lose your home in less than a month. This is how it happens. See the story

Eviction drives housing insecurity

Chambers had bills: car payments, insurance, utilities and three cellphones. Her sons were eating more because of COVID-19 school closures.

To find a new place, she needed to pay first and last month's rent and a security deposit, meaning Chambers would have to cobble together nearly $7,000 and was already starting at a deficit.

Chambers didn't have savings. Nearly 3 in 5 Americans report having less than $5,000 in savings to cover an emergency.

She struggled to find a job. Many assisted-living facilities didn't want to hire new nurses and preferred to keep staffing low because of the high risk of spreading COVID-19.

Chambers was among millions of women taken out of the workforce after the onset of the pandemic because of quarantine measures and other economic disruptions. The massive loss of jobs saw the highest number of Black women unemployed in 40 years.

Months later, after finding a new contract with limited hours and a much lower salary, it was too late. Chambers' landlords still wanted her out. Chambers received texts from her landlords twice a week: "You're going to ruin my credit score." "I'm going to therapy because you're making me depressed."

During the first two years of the pandemic, the halt in residential evictions ordered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was intended to keep about 40 million people such as Chambers safely housed.

But there were loopholes.

Chambers’ landlords could evict her if they intended to sell the property. This was one of the only ways owners could circumvent the patchwork of national and local protections in King County and Washington state.

Long before the pandemic, the eviction system was designed to be fast, cheap and easy – for landlords, not tenants. In Seattle, if tenants want to contest an eviction, they have to send a letter via fax or USPS mail. They might want to gather supporting documents and make photocopies, eating away more time. All of this can mean missing work to respond to a summons.

Without a hearing, they forfeit any chance of staying in their homes.

In most states, tenants respond to an eviction summons by appearing in court for their hearing. Research has found many tenants confuse summons for eviction orders and abandon their homes.

State laws in Alaska, Arizona and North Carolina allow eviction summonses to be served to a tenant as little as two days before a hearing, leaving them with little time to prepare, let alone to be able to take off work to show up to court. Only six of 39 states that specify a minimum summons period require summonses to be served more than a week before a hearing date, according to an analysis of eviction laws and procedures commissioned by Congress and executed by the federally funded Legal Services Corporation and the Center for Public Health Law Research at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“Anytime you add an administrative step that people take by themselves, you are increasing the risk of an informal eviction,” said Michele Thomas, director of policy and advocacy for the Washington Low Income Housing Alliance.

When women do reply, few to no safeguards exist to prevent the eviction.

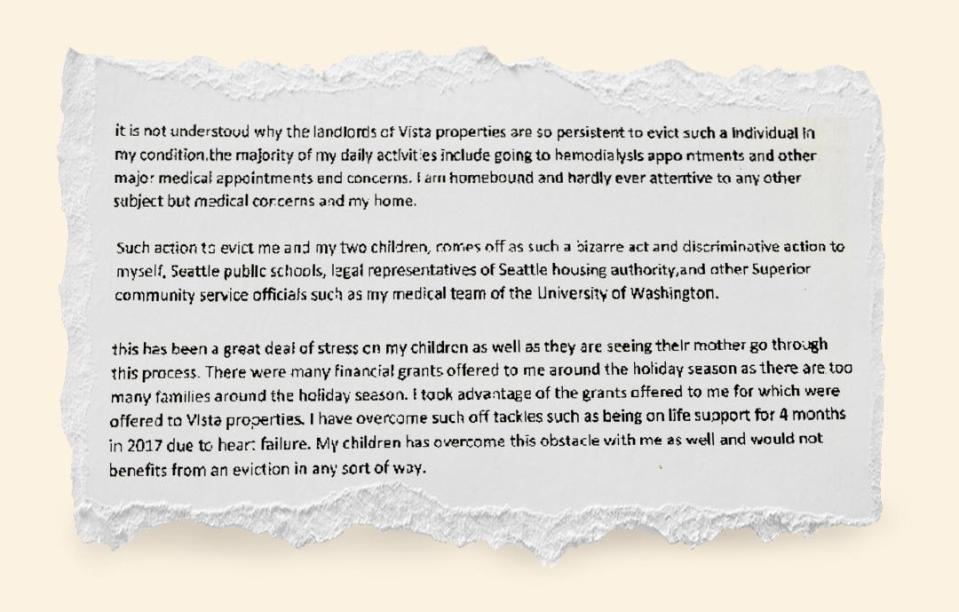

In one King County case, a Black woman who is legally blind, in a wheelchair, fighting congestive heart failure, diabetes and kidney disease, and on dialysis treatment three times a week, was being evicted for nonpayment from her apartment. Rent was paid in part with a $1,000 federal housing voucher commonly known as “Section 8.” She needed to pay the remaining $711 each month.

She was behind two months and owed $1,589.75, including charges.

The woman faxed a letter from the public library to her landlord’s lawyer explaining that her attempts to repay within the 14-day notice had been rejected and how an eviction would disrupt her and her two children with autism.

“It is not understood why the landlords are so persistent to evict such an individual in my condition. … I am homebound and hardly attentive to any other subject but medical concerns and my home,” she wrote.

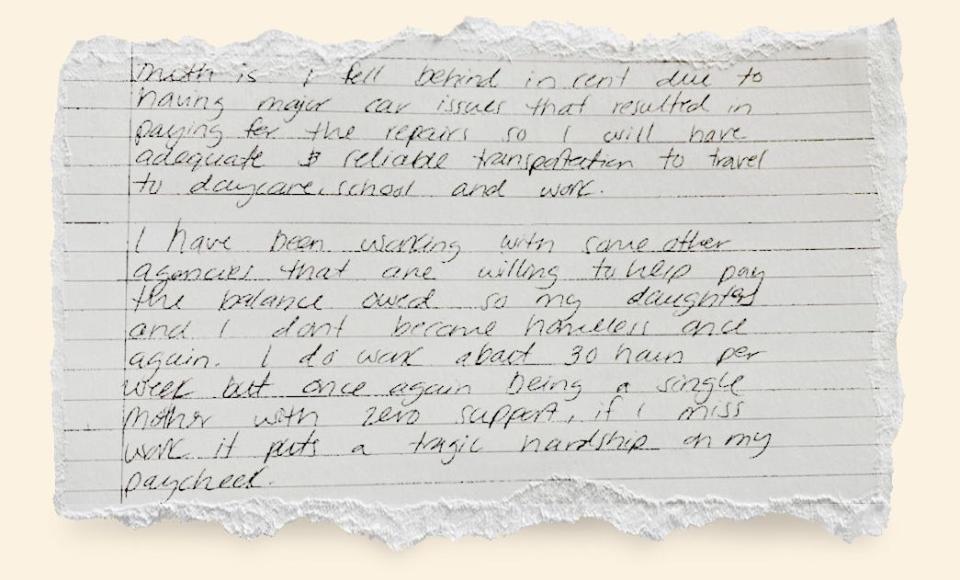

In a letter dated Jan. 1, 2020, another Black woman in King County asked if she could come up with a payment plan. She owed $1,500.

“Truth is I fell behind in rent due to having car issues that resulted in paying for the repairs so I will have adequate & reliable transportation to travel to daycare, school and work. I’m working with some other agencies that are willing to help pay the balance so my daughter and I don’t become homeless,” the woman explained.

Records show both cases resulted in evictions.

Top evictors of Black women cash in tax credits

In King County, some of the most prolific filers of evictions are developers of projects that are supposed to be designed to alleviate one of the most pressing problems in the country: the affordable housing crisis.

Five of the top 10 properties with the most evictions filed were low-income housing projects developed and managed by for-profit companies and financed using federal tax credits worth tens of millions of dollars. A disproportionately large share of the tenants are Black.

Historically, the federal government was one of the biggest developers of public housing. But in the 1980s, the government turned to the private market to look for solutions for low-income renters.

The federal government funds 90% of all subsidized rental housing through its Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program. Private developers bid for contracts to acquire, rehabilitate or build housing units in exchange for hefty tax breaks. Those tax breaks are sold to investors, such as large financial institutions, to secure financing for the projects. Investors use the credits over a period of years.

Four of the apartment complexes in King County with high eviction filing rates were developed by DevCo. In 2019, the last full year without an eviction moratorium, 36 evictions were filed against tenants of the Promenade Apartments, a sprawling 294-unit complex developed by DevCo in Auburn, about 30 miles south of Seattle. That’s an eviction filed for roughly one out of every eight units in a single year.

According to tenant data produced by the Washington State Housing and Finance Commission, 34% of the renters in DevCo’s low-income properties in King County are Black. About 11% of all renters in the county are Black.

DevCo received $25.4 million in tax credits to help finance the brand new complex, which has an outdoor pool, a recreation center and a playground. The DevCo-affiliated company that owns the property, Promenade Apartments, also wasn’t assessed any property taxes on the apartments in 2021, which were valued at $74.3 million.

The company is the largest for-profit, low-income housing developer in the state of Washington, with 7,000 units in active projects that received $466 million in tax credits, according to a USA TODAY analysis of data from the state housing commission.

DevCo did not return USA TODAY's request for comment.

Unlike public housing, monthly rents in low-income housing do not adjust based on a tenant’s income, said Vincent Reina, associate professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania. In an expensive rental market such as Seattle, even what qualifies as affordable housing can often be a financial stretch for low-income renters.

“Rent being below market helps, but it’s not the total solution we’re looking for,” Reina said. “For a lot of households, there’s a much deeper level of subsidy that's needed for it to be truly affordable.”

Another for-profit developer of low-income housing, Goodman Real Estate, had a 21% eviction filing rate at its 252-unit apartment building, Addison on Fourth, in downtown Seattle.

In a statement to USA TODAY, Goodman Real Estate CEO George Petrie acknowledged high eviction rates for the building in 2018 and 2019 but blamed a Seattle ordinance enacted in 2018 that banned the use of criminal background checks in tenant screening.

"Over 500 people have lived in the Addison over the past two years, but management finds out about a resident’s criminal past only when the police arrive and arrest someone on the premises,” the statement said.

According to Petrie, a majority of evictions filed were for behavioral issues.

"A stabbing; allowing drug dealers to take over the apartment; bringing trespassers into the building; harassing/assaulting staff; being aggressive with neighbors; damaging the building; and prostitution," Petrie said.

USA TODAY reviewed all of the eviction filings at Addison and found that all but three evictions had been filed due to nonpayment of rent. The amounts varied from $50 to $4,320.

What should I do if I’m being evicted? Here are some tips

Read in English here. Leer en español.

Official records from the Washington State Housing and Finance Commission show at least 16.4% of tenants housed at Addison identified as Black. Demographic information was not disclosed for 58% of tenants.

Goodman Real Estate received $10.3 million in tax credits to finance the renovation of the apartments at Addison on Fourth.

Both developers and their related companies received millions of dollars in emergency rental assistance from the federal American Rescue Package passed in March 2021. Congress passed the measure to stave off evictions for about 40 million renters and make landlords whole.

DevCo-related limited liability companies received $5.4 million for tenants at the four low-income apartment complexes, and Goodman Real Estate received $280,000 for tenants at Addison on Fourth, according to records from the King County Department of Community and Human Services.

Goodman Real Estate, which has properties in multiple states, said in 2020 and 2021 it helped its tenants receive a total of $23.5 million in rental assistance.

"The problem is that we have outsourced and privatized affordable housing. When this happens, these companies are going to behave like private landlords," said Peter Hepburn, a professor of sociology at Rutgers University in New Jersey and an analyst with the Eviction Lab at Princeton University.

Many cities could soon see a wave of evictions, in part due to rising rent prices, said Democratic Washington state Rep. Jamila Taylor. Others will be forced out of their homes without a single legal document being filed, she predicted.

"What really happens is that a landlord doesn't have to file an eviction on someone if they raise rent 100%," Taylor said. "It's just going to force that person to move without waiting for an eviction notice or a three-day pay or quit notice."

How did USA TODAY calculate racial and gender disparities?

For the analysis of King County evictions by race and sex, USA TODAY used data from the evictions.study project, a collaboration among researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, and the University of Washington. To predict the race and sex of renters in eviction filings, the researchers applied a computer model that used name and sex data from the Social Security Administration, and name and demographic data from the U.S. Census.

USA TODAY also analyzed thousands of eviction filings obtained from the King County Department of Judicial Administration for company-level filings figures.USA TODAY used 2016 eviction filing data by race and county from the Eviction Lab at Princeton University for national figures.

A right to counsel

At the center of the country's housing system is a systemic imbalance of power. For people who can’t afford a month of rent, hiring a lawyer to delay or stop an eviction is often not an option. Because evictions are civil cases, tenants aren't guaranteed access to a lawyer in many cities.

Roughly 90% of landlords have legal representation in eviction court, but fewer than 10% of tenants have legal assistance to defend their home, according to a report from the American Civil Liberties Union.

A private attorney will charge on average $100 to $400 an hour to fight an eviction order, and filing fees begin at $200. If tenants lose their case, they might be on the hook for their landlord's legal fees, which could be many thousands of dollars.

"A right to counsel for tenants is critical," said Rasheedah Phillips, director of housing for Policy Link, a national research institute focused on race and economic equity. "You often need a lawyer experienced in landlord-tenant law to understand how to navigate the court process, no matter what your level of education is."

For Melody Rivers, the legal battle over her home in Auburn began when she woke up in a hospital bed howling from sharp, shooting pain.

"Help," she yelled as she pressed the call button in her hand.

Rivers, 59, a Black military veteran who served in Germany during the Cold War, had seen better days. Within six weeks, she had suffered a near-fatal car crash and been pink-slipped. That was all before her emergency surgery when a surgeon removed cancer from her colon.

Unable to move, the bookkeeper acted fast to try to cover her rent that month. She asked the hospital’s social worker to help her fill out paperwork to claim a short-term disability policy from her insurance company.

"We'll take care of sending everything out by the end of the week," the social worker told her.

When Rivers arrived at her doorstep after being discharged a week later, there was a pay or vacate notice taped to her door. Rivers ripped the paper and slammed the door on her way in. She waddled over to her room and sat atop the oak sleigh bed with the gold comforter. She felt the pain from the incision.

"I couldn't even walk, and I was about to get evicted," Rivers said.

She took her medication, pulled the covers over her head and fell asleep.

The next day, she phoned the Department of Veterans Affairs for help. The VA offered to make a partial payment of $879 as long as her landlord completed a form. If she could receive that amount and her unemployment as she waited for the insurance's response, it would be enough to keep her current.

Her landlord refused.

Rivers hoped the judge would side with her during the eviction hearing. That morning, as she drove downtown to the courthouse, Rivers repeated to herself: "There's nobody that can speak for you better than you, Melody.”

Rivers walked into the courtroom with the marble floors and sat in the third row of the wooden benches.

She looked up and saw the judge. Then her landlord and next to him lawyers with their briefcases. Rivers sat alone.

The bailiff called her name. The landlord's attorney read off the facts of the case: She owed two months of rent.

"Ms. Rivers, how do you wish to respond?” the judge said. “You can only ask questions that can be answered with a yes or with a no."

Rivers felt her body temperature rise. This was her only chance to explain everything, to let them know she had tried to find a solution.

Rivers blurted out, "Why don't you want to fill out the paper? That's what I want to know."

The judge ruled in favor of her landlord.

"In less than 10 minutes, everything had been decided, and I was going to lose my home,” Rivers said.

Rivers’ landlord was represented by the Seattle-based law firm Puckett & Redford, which represents landlords in nearly half of all eviction cases in King County. Puckett & Redford declined to comment for this USA TODAY investigation. USA TODAY was unable to reach Rivers' landlord for comment.

In April, Washington became the first state to create a right to counsel for tenants facing eviction. In communities with right to counsel, 86% of renters were able to remain in their homes, and eviction filings decreased by 10%.

It was too late for Rivers, who had already lost her home. In the two years since she was evicted, she hasn’t been able to get her own place, forced to stay first with friends and now with her boyfriend.

Her landlords, on the other hand, sold the 16-unit building in August 2019 to a corporate landlord – six months after she was displaced.

Evictions lead to being blackballed from the rental market

When her children were younger, Chambers was able to keep a home for her three sons on public assistance. For a decade, she depended on her Section 8 voucher – the federal program that pays a large portion of very low-income Americans’ rent – while she put herself through nursing school and cleaned houses.

"I decided I made enough money with nursing and cleaning houses that I could afford to pay full rent on my own, and I turned in my voucher," Chambers said.

She moved into the green-sided home, and when times were good, she spent any extra cash on antique furniture. Chambers especially loved her Victorian chair upholstered with blue and yellow swirls.

“Each room had its own particular style. It was just so beautiful, I wish you could have seen it,” Chambers said. "Now all I have to show is how hard I have fallen."

When moving day came, Chambers spackled the holes her sons had accidentally left in the walls with a putty knife.

Hours later, her son, Michael, who is legally disabled and bipolar, punched another hole in the freshly repaired wall.

"It was a lot for my two kids to understand what was happening," Chambers said. "Those were the hardest days. Not having any help to move out. The triple-degree heat."

Chambers hoped she might avoid eviction if she reached a settlement. Pandemic restrictions in Washington caused the eviction process to drag on for seven months.

She applied for emergency rental assistance from King County. Her landlords received $19,792.93 of back rent, legal fees and court charges – every penny she owed.

An eviction still appears on Chambers' record because potential landlords are able to see all filings, as opposed to only the outcome. Landlords typically use third-party tenant screening companies to filter through prospective applicants. These companies pull information including expunged or sealed criminal records. Companies can make mistakes if applicants have the same name.

Similar to an arrest record, an eviction record can follow tenants for decades, drastically limiting their opportunities to start over.

In some states, including Washington, tenants can receive an order from the court that stops screening companies from showing an eviction. According to a copy of Chambers' signed May 11, 2021 settlement reviewed by USA TODAY, her landlords agreed to such an order in exchange for receiving what they were owed.

The order has not been filed almost a year later.

Chambers said she called her landlords several times but they have been unresponsive.

Chambers' landlords declined to be included in this story.

Chambers' options were restricted by her income. Since 2021, rent prices have skyrocketed 14% nationwide and 25% in Seattle.

Chambers could move to only one place. She had a friend who knew a guy who rented apartments. No credit check. No backgrounding. She signed a two-year lease for an apartment in north Seattle for $2,000.

Five months after the eviction, Chambers, who had prided herself on living in a magazine-worthy house, was living without working heat, a dishwasher or hot water in the upstairs bathroom. Moving boxes from the old house were stacked floor to ceiling in the living and dining rooms of Chambers' apartment. Dishes were piled in the sink. She taped the unfinished stair railing together to make it safer.

"We have to leave the oven on to warm up the house," Chambers said.

Chambers turned to the gig economy – first as an Instacart shopper, then on Handy to clean houses. Inflation began to creep in. Her car was repossessed twice. She borrowed money from her dad in Alabama. There's $5,000 worth of jewelry at the pawn shop – all to never miss a rent payment again.

"All of this stuff snowballed after I moved out, everything became a hassle to pay," Chambers said.

Some nights, Chambers was so exhausted she'd fall asleep immediately on the mattress on her bedroom floor. Others, she would stay awake, ruminating with her 9-year-old chihuahua, Estelle, next to her about the home she lost.

On the day before she moved out of the green house, Chambers sat down to drape her beloved living room furniture in bubble wrap. There was a four-piece Persian set with a sofa and three throne chairs. The chairs had gold, hand-carved roses overlaid with lush fabrics and had cost her $7,000. Chambers lovingly touched each item, the possessions she had worked so hard for.

"This home in Auburn was proof that I had made it, that I had gotten out, and now everything was gone," Chambers said.

Follow USA TODAY reporters @RominaAdi and @kcrowebasspro on Twitter.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black women are getting evicted at highest rates across United States