'I lost everything': laid-off workers battle Florida's chaotic benefit system

A year since the first coronavirus case was reported in the US, millions of Americans have found themselves out of work for nearly all that time as the pandemic triggered an economic crisis on a scale unseen since the Depression of the 1930s.

Florida has been hit harder by the pandemic than nearly any other state and the crisis has wreaked havoc on countless lives, families and communities from the Florida Keys to the Panhandle – and everywhere in between.

Related: US companies using pandemic as a tool to break unions, workers claim

The state experienced the second most unemployment claims in the US since the start of the pandemic, with an unemployment increase of 1,683% compared with January last year, according to data compiled by WalletHub.

Florida has recorded over 1.6m cases and more than 25,000 deaths since the start of the pandemic, the third highest case count among states in the US and fourth in total deaths, although its population, at nearly 22 million, is the third largest.

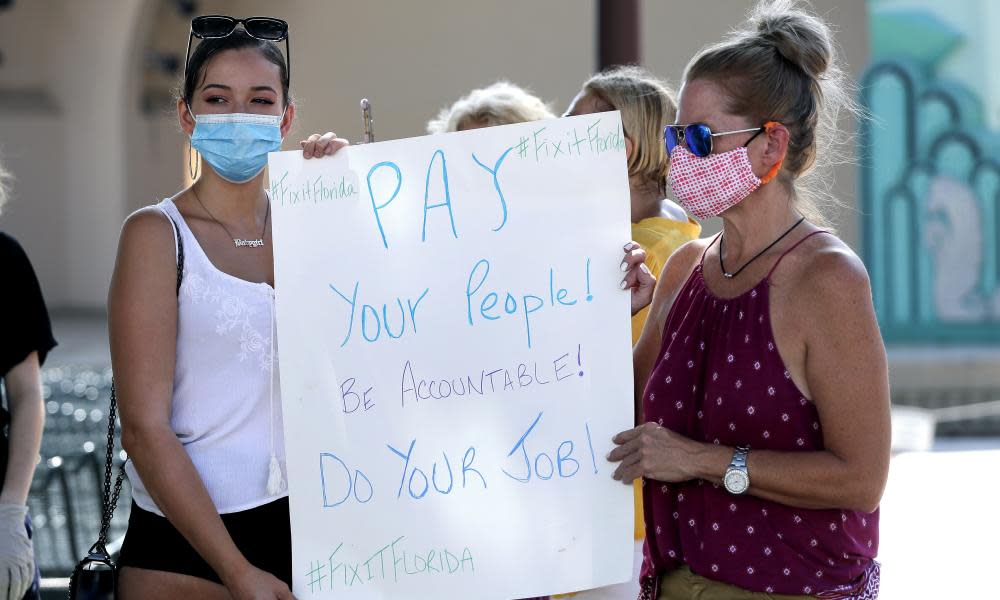

Workers who have lost their jobs have been forced to rely on a broken state unemployment system that has experienced long delays, backlogs, system crashes and small payments as the state’s maximum payout of $275 covers only a portion of the lost income for thousands of workers in the state.

Through 2020, Florida was the second worst state in the US at paying unemployment benefits on time. Internal audits had uncovered various issues with the state’s unemployment system for years before the pandemic hit, and elected officials are still conducting reviews on how to fix the state’s ongoing unemployment failures.

The Guardian spoke to workers in Florida who have struggled to survive while relying on the state’s broken unemployment system.

Here are some of their stories.

Ann Largent

Former hotel employee at Disney World in Orlando for two years

Right before coronavirus shut down Orlando’s tourism industry, Largent was separated from her job of two years at a Walt Disney World hotel, where she worked late-night shifts conducting maintenance and housekeeping duties.

Orlando, one of the most visited tourist destinations in the US before the pandemic, has taken among the hardest hits in job losses as its theme parks, Disney World, SeaWorld, Universal Studios, and others have permanently laid off thousands of workers.

The surrounding area has maintained the highest unemployment rates in the state, with an estimated 125,000 jobs lost over 2020.

Largent was one of thousands of Floridians who experienced long delays in receiving unemployment benefits through the state. During that time, Largent and her daughter had to leave the house they rented because they could no longer afford it. They moved into a mobile trailer park where they currently reside because rent is too high anywhere elsenearby.

“During that time frame, I lost everything,” said Largent. “Covid-19 has destroyed my life.”

Her car was rear-ended by a truck while she awaited unemployment, and because the driver had no car insurance, she hasn’t been able to repair the damage. Her own car insurance expired last month because she can no longer afford the payments. That puts her driver’s license at risk, which she needs not only in hopes of finding a job, but for taking her 12-year-old daughter, who is currently in remission from cancer, to doctor’s appointments.

I lost my health insurance because Medicaid said I was making too much money on unemployment. I only get $247 a week

Shortly after she finally started to receive unemployment benefits, her Snap food assistance benefits were cut from $355 a month to $16 a month. Then the federal extended benefits of $600 a week expired on 26 July, leaving Largent and her daughter to survive on just $247 a week, Florida’s maximum unemployment payout after taxes are deducted.

After submitting hundreds of job applications, she finally received an offer to start work as a patient care technician at a nursing home, but after working one day was never provided a full schedule.

Her unemployment benefits were stopped due to a hold placed on her account for working one day. It took a month for Florida’s department of economic opportunity to remove the hold after weeks of Largent calling for help, spending hours on hold trying to speak with service representatives. While her benefits were on hold, she fell behind on rent.

Largent also experienced her own health issues while trying to survive on unemployment.

“I lost my health insurance because Medicaid said I was making too much money on unemployment. I only get $247 a week. How am I making too much in unemployment? All that pays is my rent,” she said.

The health insurance difficulties occurred while Largent required medical attention after she was bitten by a black widow spider on her ankle, and almost lost her foot as a result.

Her daughter has struggled through the pandemic, in transitioning to a new, smaller home, struggling with virtual learning and worrying about catching the coronavirus as a cancer survivor with a compromised immune system.

Largent explained her daughter’s personality had changed due to the lockdown, from very outgoing and talkative to quiet, reserved and shy.

Delaun Stokes

Former server at Macaroni Grill in Orlando for two years

Stokes worked as a server at Macaroni Grill at Orlando international airport for two years before the coronavirus hit the US and he lost his job.

In March, Stokes explained everything started to change suddenly. First tables were cut and spread out to socially distance customers. The next week, Stokes and his colleagues were informed the restaurant was going to be shut down, and he would be furloughed until things returned to normal.

By August, his restaurant was still shut and he received a letter informing him that his furlough would be a permanent layoff by 15 October.

It went from keeping myself afloat, paying bills, to wondering where I’m going to get my next meal

He received unemployment benefits right away unlike thousands in Florida but things got much more difficult when the extra $600 a week of federal extended benefits expired on 26 July.

“It went from keeping myself afloat, paying bills, to wondering where I’m going to get my next meal, if I’m going to have enough to pay rent or use what little I had to get food that week, trying to juggle things around got hard,” Stokes said. “The coronavirus relief hasn’t been enough, so we need something more. For the elected officials who are fighting for it, I thank them from the bottom of my heart. For the ones who oppose it, all I have to say is we’ll see you guys next election day.”

His mother and stepfather moved out of the area during the pandemic to follow work in audio engineering, so he’s spent the duration of the pandemic without the support system of a family nearby.

Stokes and several of his colleagues at Orlando airport have held protests to push local elected officials to pass legislation to ensure workers who lost their jobs during the pandemic are provided recall rights to return to their jobs when their workplaces reopen.

“We need assurances to make sure we can go back to our jobs. It’s only fair and it stops us from having to worry about what’s going to happen next,” Stokes added.

Maria E Gonzalez

Former cashier at Sbarro in Orlando for four years

On 26 March, Gonzalez’s manager at Sbarro pizza assured her the furloughs would be temporary only to receive a letter five months later announcing her layoff would be permanent by 15 October.

She’s had several problems with Florida’s unemployment system since she first applied for benefits.

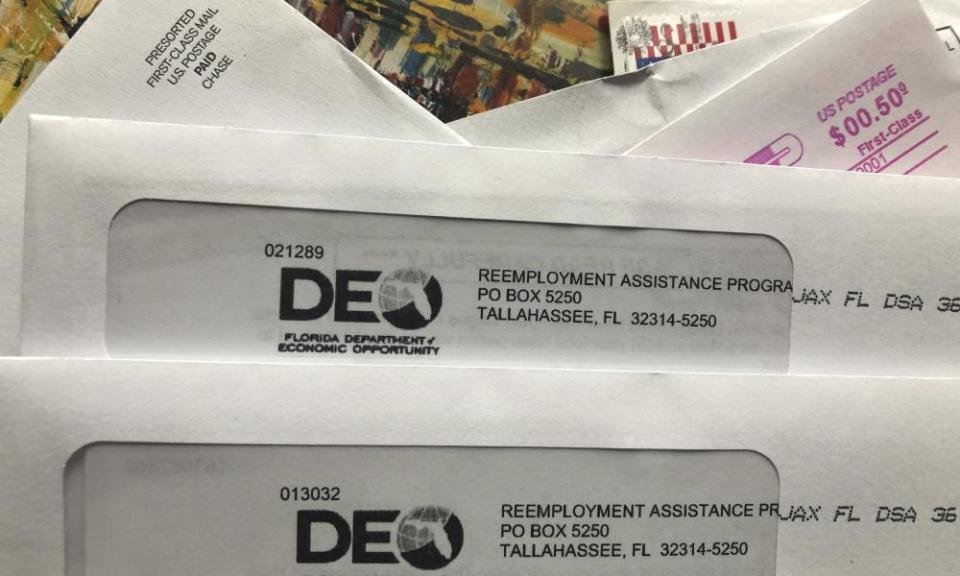

When Gonzalez first applied, her application was delayed because she was required to provide her birth certificate after the Florida department of economic opportunity requested further documentation to verify her identity.

I call unemployment every single day for the benefits. I’m told they don’t know when I’m going to receive them again

In August, Gonzalez worked a temporary job organizing in support of the Biden campaign in Florida, but her job was discontinued after two days because the organization was experiencing technical issues.

“I reported this to unemployment and they’ve kept me on hold for months, and I’m still on hold five months later,” said Gonzalez. “I call unemployment every single day for the benefits. I’m told they don’t know when I’m going to receive them again, they don’t have a time frame, just that they’re fixing it. They said they owe me a lot of money, but they still haven’t given it to me, so I’m having to depend on friends and family to help me with bills because I’ve been behind.”

On a daily basis, Gonzalez is harassed by calls from creditors demanding payment, but because of her ongoing hold with unemployment, she’s been unable to pay her bills. Even when she manages to work something out with a service agent for a creditor to defer pay for a month or two, she still receives calls demanding payment while late fees and interest are piling up.

“I’m frustrated. I’m depressed,” said Gonzalez. “I don’t know what’s going to happen in my future, even in the next month. I don’t know what to do.”

Williams Alvarez

Cargo worker at Miami international airport for 10 years

For 10 years, Alvarez, an immigrant from Cuba, worked as a cargo employee for the contractor Eulen America at Miami international airport.

When coronavirus began spreading around the US in March, Williams noted there was immense pressure at work, as personal protective equipment shortages were widespread, and there were ongoing rumors workers would be laid off.

On 23 March, Williams received his layoff notice and has tried to survive on unemployment ever since.

Like thousands of Americans who were suddenly laid off or furloughed, Williams spent every day for weeks trying to call and log on to unemployment to process his application, but the phone lines were always busy and the website kept crashing.

After six weeks, he started receiving benefits, but continued trying to help co-workers secure theirs. During the wait, his bills began piling up, and he’s been behind ever since.

It’s already been almost a year and I constantly feel like I’m drowning, raising my hand for help, but being ignored

“My car broke down, but I’ve only been able to afford to get part of it fixed,” said Williams. “I broke my tooth and had other dental issues, including an infection as a result of dental problems. My uncle passed away, and afterwards responsibilities of caring for my aunt and my mom fell on to me and that’s made it really difficult for me to try to get ahead.”

When the federal unemployment benefits of $600 a week expired on 26 July, Williams started falling further behind. He managed to work out a payment plan for his car and mortgage to defer payments for six months, but this February he is expected to restart payments.

With the new presidential administration coming in, Williams has some hope things will improve and future coronavirus relief packages will focus on helping the working class and frontline workers.

“This whole pandemic has physically and mentally impacted me. I’m frustrated. I want things to change, but things aren’t changing. It’s already been almost a year and I constantly feel like I’m drowning, raising my hand for help, but being ignored,” he concluded.

Jilma Guevara

Cargo security officer at American Airlines subcontractor in Miami for seven years

Guevara was shocked when she received a layoff notice on 23 March. For weeks in March there was a lot of insecurity and anxiety about coronavirus, but she had the most seniority in her department, a spotless record, was a backup supervisor, but was the first person laid off in cargo.

“I felt like the roof fell in on my head. I’m diabetic, we were already living through this feeling of anxiety because no one was telling us at work what was going to happen with the pandemic, and then I asked myself, what was I going to do without any money?” Guevara said. “I felt humiliated and betrayed. My co-workers and I gave the best of ourselves so we could make American Airlines and other airlines look good, so to me it was a betrayal, a stab in the back.”

In October, a congressional subcommittee released a report on various airline contractors who misused coronavirus relief funds, as delays in the disbursement of funds allowed contractors to conduct mass layoffs, then subsequently keep payroll relief funds for pre-pandemic jobs.

The politicians don’t have any idea what’s happening, their salaries keep coming

It took nearly three months before Guevara started receiving unemployment benefits. She relied on former co-workers and friends to help pay for her diabetes medication, food and other bills. She applied for Snap benefits and began applying for other jobs, even though her health issues make her particularly vulnerable to a coronavirus infection.

Shortly after she started receiving unemployment benefits, the extra $600 a week of federal extended benefits expired, leaving her with just $1,000 a month in income to cover her rent of $1,575, her medications which cost $400 a month even with reduced costs through a clinic, and for food and other bills.

“The politicians don’t have any idea what’s happening, their salaries keep coming. Meanwhile, the average worker, we earn every dollar through our sweat. And either way, life is invaluable. That money helped us stay home and protect ourselves from the pandemic,” Guevara added.

Ramona Vera

Airplane cabin cleaner for 10 years at Orlando international airport

Ramona, 65, and her husband have relied on food banks throughout the pandemic. Their diet has primarily consisted of rice and beans, or whatever food they could afford.

“We haven’t been able to eat like we used to eat before. We can’t go out to eat. We can’t buy meat because it’s so expensive,” she said.

When she first lost her job in March, it took about two months to start receiving unemployment benefits after struggling to process her application, and she never received back pay for the weeks of benefits she missed.

She receives $500 a month in social security benefits, most of which goes toward her health insurance. While waiting on unemployment, she fell behind on mortgage payments for her mobile home, but managed to get an extension until May 2021. She has no idea how she will pay the back payments she owes.

The money we do get immediately goes right back out to pay off bills

“I haven’t been able to pay the mortgage. I’m behind on my credit card bills and my utility bills. I don’t know what I’m going to do right now because it’s been extremely difficult finding work. I’ve been looking everywhere, applying for jobs,” Ramona said.

It’s been even more difficult trying to find a new job at her age, and she’s frequently tried to get a job at nearby Walmart stores despite the ongoing risks of coronavirus. Her hopes heading into 2021 are to find a new job so she can afford to survive and to eventually pay off the $106,000 mortgage on her home, which she was paying for three years before the coronavirus hit.

“Being without work, and little money coming in, there are a lot of bills and it’s frustrating because there’s no help coming from anywhere. The money we do get immediately goes right back out to pay off bills,” she added. “I’m hoping the mortgage lender gives me some kind of payment plan because right now I can’t pay back the money I owe. They told me I have to pay $7,000 when the extension ends. No way I can pay that.”

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Sidney Hillman Foundation