The lost legacy of Okemah: A historic Black community in Phoenix decimated by highways

A century ago, when Phoenix was segregated, hundreds of Black families found faith and belonging southeast of downtown in a community called Okemah.

The area along the Salt River between roughly 32nd and 48th streets bounded by Broadway Road to the south didn't have much.

The community went without utilities and running water for decades. The roads weren't paved for most of its existence. Kids swam in the same canal that families used for fishing and churches used to baptize families.

But the way former residents of Okemah remember it today, they were still rich.

"We were rich in terms of our spiritual growth, how we were cared for, how we were made to believe that if you believe you can do it, you can do it," said Josephine Pete, who lived in Okemah between 1949 and 1966 and is now in her 80s.

Pete remembered an older gentleman in the community would travel to pick up a copy of the Pittsburgh Courier to bring back and show the Okemah families.

It was "motivation to see all these Black people dressed and in the newspaper," Pete said, "because, at that time, we did not have a little Black newspaper."

One of the community's beloved school teachers refused to let the boys play marbles on their knees. Principal Leatha Slaughter knew it ran the risk of damaging the kids' pants, and parents didn't have the money to easily replace them.

Family, faith and an unrelenting commitment to the next generation was everything in Okemah, Pete and other former residents remembered.

But Okemah was torn apart by the construction of Interstate 10's Broadway Curve, which opened in 1971. The freeway split the community and demolished families' homes.

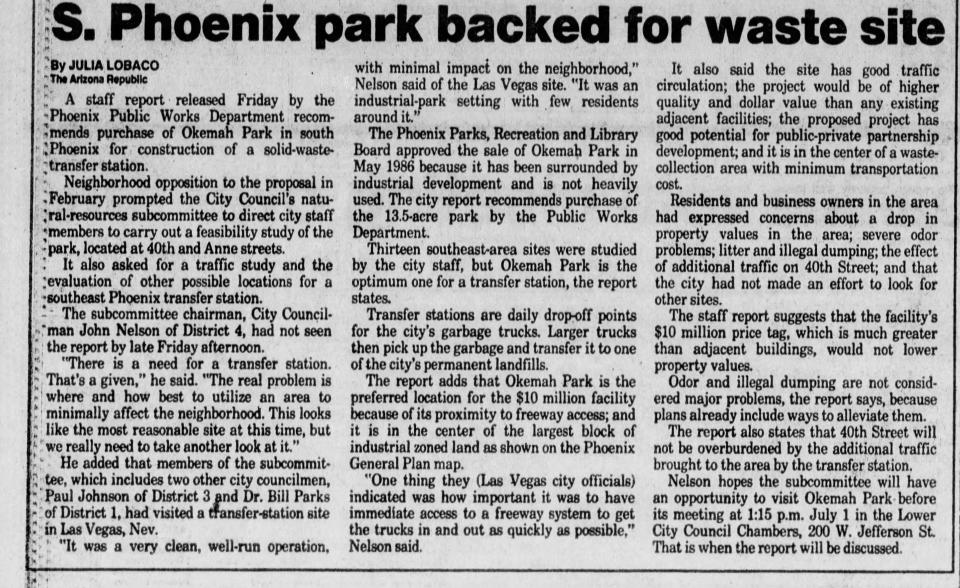

Phoenix targeted the area for industrialization, hoping to leverage its proximity to the Phoenix Sky Harbor International Airport. Okemah's park was turned into a landfill, and homes were turned into office space. School districts had begun separating Okemah's children years earlier, hindering their connection.

Phoenix barrios: Interstate highways displaced thousands in Phoenix. The consequences were long-lasting

It all culminated in the deterioration of the community, where even when residents could stay because the freeway hadn't replaced their homes, they moved anyway to flee the disruption.

"The most devastating thing, I think, was the community died," Pete said. "Or it was overtaken."

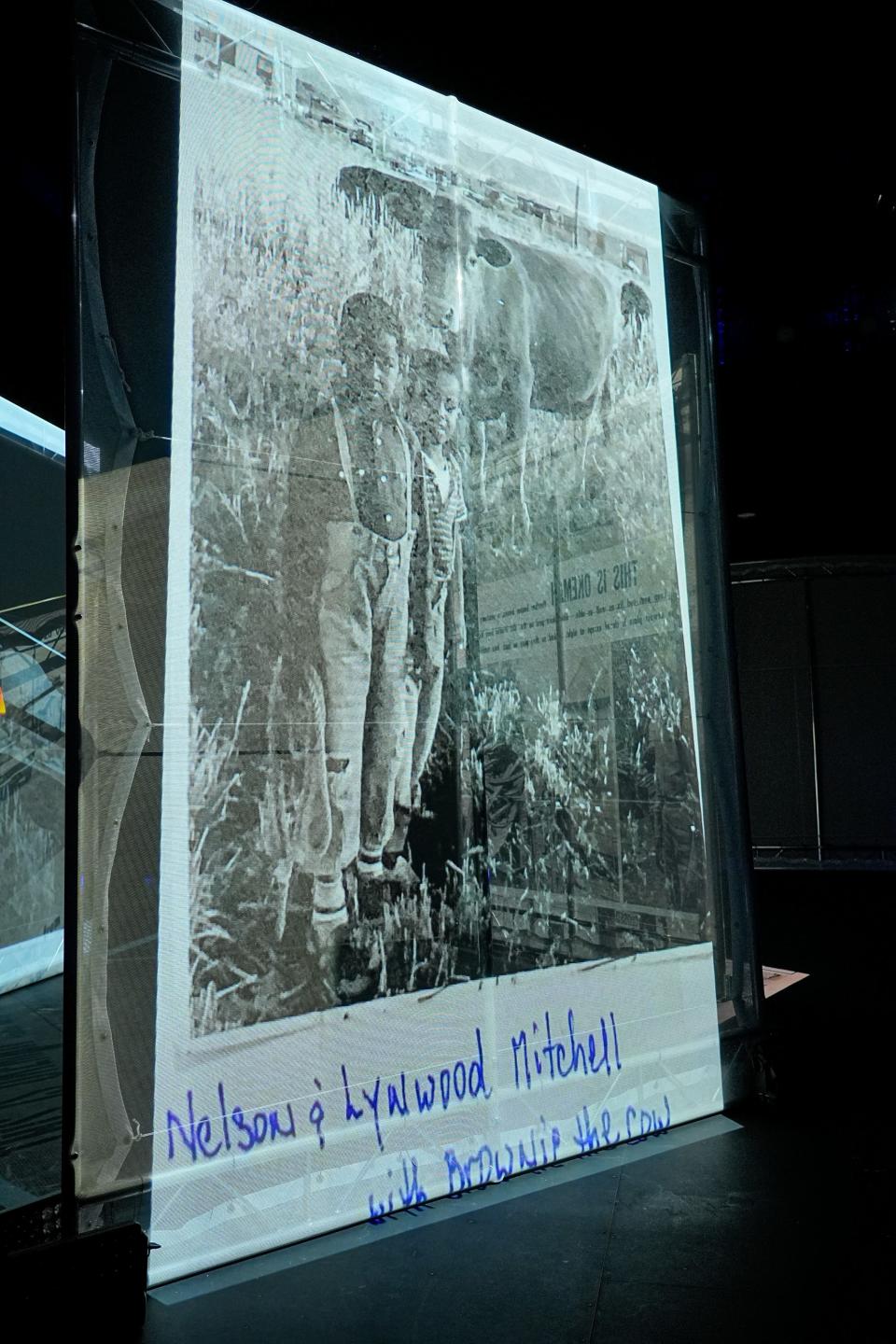

Nelson Mitchel III, another former resident who lived there between 1953 and 1978, said families lost "a refuge ... a sense that we were all for each other and that we could all depend on each other."

But while the community itself is no longer, its legacy and values have lived on.

Pete, Mitchell and other former residents, including Doris Lamkin Burt-Johnson, Gloria Daniels Williams, James Boozer, Bill Mosley and others, have worked diligently to ensure the memory of Okemah is not forgotten.

They formed the Okemah Community Historical Foundation, which is dedicated to preserving and sharing the community's story. They also launched an educational scholarship for Okemah descendants. Those with connections to the community still gather annually to reminisce and celebrate its history.

Burt-Johnson's husband, William Burt, published the book, "Arizona History: The Okemah Community," which documents the community's origins.

Arizona State University film professor Carla LynDale Bishop has also taken up the cause of recording Okemah's history.

Bishop is the creator of a large-scale project called "Mapping Blackness," an app that will allow the public to explore historic Black communities in all 50 United States.

The project has not yet launched, but Bishop is beginning with Okemah. On Saturday, Feb. 10, from noon to 5 p.m., Bishop will host an interactive community event at the MIX Center in Mesa to present her work.

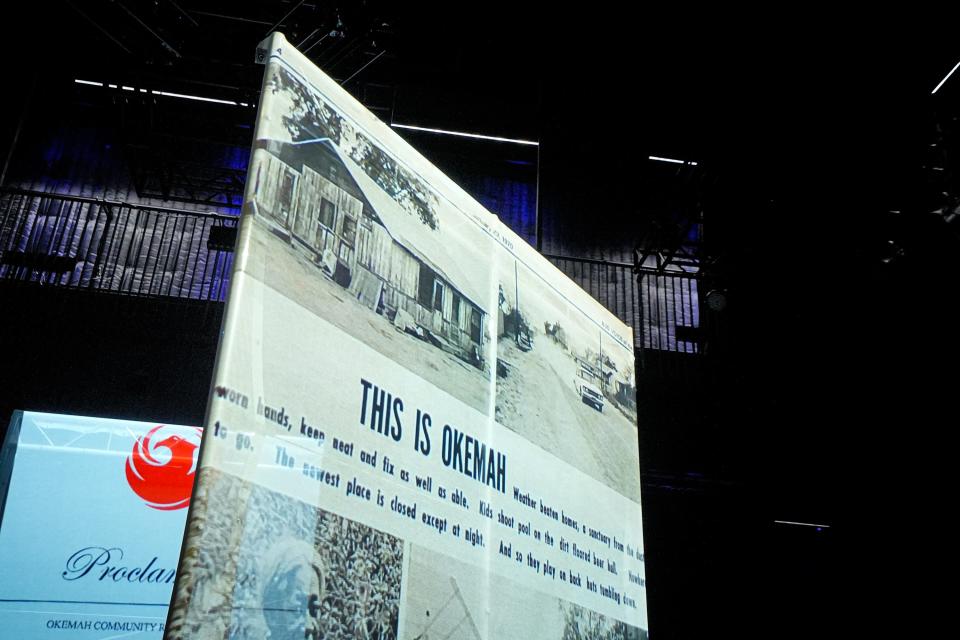

The event will showcase a 360-degree virtual reality experience to transport viewers back in time to visit Okemah. A black-box studio will project large-scale photos and videos from the community, plus interviews with former residents, such as Burt-Johnson, who lived there between 1958 and 1964.

Bishop invited former Okemah residents to attend and said the event will be a celebration of the joy and pride that permeated the historic community.

Okemah through the years

Okemah families came mostly from Oklahoma, but also Texas, Louisiana and Arkansas in search of work. They named their community after Chief Okemah of the Kickapoo Tribe in Oklahoma — an homage to a man they deeply respected and admired in their home state. The chief was remembered as highly intelligent, a quality the residents wanted to emulate.

"People were looking for opportunities, but they were also moving out of the South because of the oppression and the violence," said James Boozer, who is 82 and lived in the community between the late 1940s and mid-1960s.

The families had been recruited by the Colored American Realty Company in 1910 to grow cotton and raise hogs, poultry and dairy stocks on Bartlett Heard Ranch.

The 6,070-acre ranch was owned by white real estate investors Adolphus C. Bartlett and Dwight B. Heard. Okemah was one portion of the ranch.

By 1927, the ranch was divided into smaller plots that Black families could afford to purchase.

Most families owned at least an acre, although some owned more. William Burt wrote in his book that families hauled water from farms or nearby gas stations. They also set out buckets to collect rainwater and used the 3.25-mile San Francisco Canal to fish.

The same year, Okemah residents were proud to see community members Luke Conley and Jack Buzard appointed to positions at the Maricopa County Sheriff's Department. Sgt. Allee Haywood of Okemah would later become a deputy sheriff, according to Burt.

The men were supposed "to take care of the official work among their own people," Burt wrote.

The federal government's Works Progress Administration, set up to provide jobs during the Great Depression in the 1930s, also provided training opportunities for Okemah residents starting in 1937.

"A lot of our young fathers participated in that program," said Burt-Johnson. The program paved the way for residents to get jobs in masonry and building parks, she said.

In the 1940s, utilities came to Okemah. Public transportation would arrive later, too, connecting residents "to further education, more shops, better jobs, and other Black communities," Burt wrote.

Mitchell's family built the first "modern" home when utilities came. His father, Nelson Mitchell II, who was in the Navy and survived the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, would send money home while deployed. Mitchell's grandfather, Nelson Mitchell Sr., used the funds to build the house, which featured inside bathrooms, water from a well, central cooling and a detached garage.

Okemah families took pride in owning homes. Segregation, federal redlining and restrictive covenants barred Black people from living north of Van Buren Street.

'Institutionalized racism of the past': Discriminatory housing practices resound in south Phoenix today

"People could live in camps and facilities (in other Arizona cities), but Okemah was one of the places where you could come, buy land and own your own home," Pete said. "It provided better opportunity."

A man named Rollin Howard donated land for the area's first park in 1945, called Okemah Park at 38th and Anne Streets. Another man, whose identity remains unknown to the community, would come sporadically and set up a projector for kids to watch movies in a field along the canal.

Children entertained themselves by making handmade wagons, walkie-talkies with cans and string, and homemade kites.

Later, the community would establish a daycare and rest home for the elderly and disabled.

The decline: freeways, industrialization and environmental injustice

President Dwight D. Eisenhower's Federal-Aid Highway Act, signed into law in 1956, sealed the lid on the coffin for Okemah. But its effects wouldn't be felt immediately.

The law built 41,000 miles of interconnected highways across the nation. It came in the era of Cold War tension. Its proponents said highways were necessary for national defense. In case of an attack, people in densely populated cities would need roadways to evacuate.

Across the country, highways were placed directly through towns, bisecting neighborhoods and changing the social fabric of communities. Some were routed through predominantly Black neighborhoods that government leaders considered unsightly.

In cities like Chicago, “urban renewal” programs used highways as barriers between Black and white parts of town.

In segregated Phoenix, Black and Latino residents who were sequestered in the south had less say than white residents north of downtown about where the highways should be placed.

Interstate 17's Durango Curve opened in 1963, bordering the southwest edge of a historic Black neighborhood, referred to as the “west region” in a City of Phoenix report documenting historic Black properties. It also divided Latino barrios.

The next segment, the Broadway Curve, cut a second wound through south Phoenix in Okemah.

In a City of Phoenix report, a woman who moved to the area in 1948 named Mary Boozer remembered being displaced.

“You feel kind of lost, like they are pushing you out of your home. After I moved out of there, after I found out they were tearing my house down, I couldn’t go down there,” she said.

The construction of the interstate freeways led to years of construction and increased noise and air-quality pollution.

The Mitchell family home, Okemah's first modern residence, was condemned, Mitchel III said.

Pete's old home is now gone. The front yard is a parking lot, the back portion a freeway. One of the community's churches is today a location for storage containers. One of the old schools is now an Amazon facility. The city converted Okemah Park into a waste station despite the residents' objections.

The community, Mitchell said, was "essentially cut in half." The freeway construction was a "constant pain" and concerns about air quality, pollution and noise abounded.

"Those are the kinds of environmental injustices we were forced to live in.

Not necessarily by choice," Pete said. "It was society's way of separating the haves from the have-nots."

Accelerating the end of Okemah was the fact that its residents were aging. Younger generations were interested in branching out, and while racist stigmas persisted, federal fair housing laws made that easier. Anti-discrimination laws for the workplace helped, too.

Plus, families had received compensation if their homes were replaced by the freeway, which meant they could, in some cases, afford to buy new property.

The values to be remembered

In adulthood, after moving out of Okemah, Burt-Johnson wrote a poem about the community and its values.

"We had our beliefs, opinions and ideas. Confidence and courage taught down through the years. Taking what we learned, it was time to stand alone. To face the world, we couldn't go wrong. We had good teachers, we learned it all. And never dreamed of taking a fall," she wrote.

Mitchell III, whose first modern home was condemned by the city, said while his family moved on and made new friends in other areas, "there was nothing like the environment that we grew up in ... where everybody in the community knew each other cared for each other looked out for each other."

Okemah's philosophy centered on family, church and education.

Parents were committed, former residents said, to ensuring children were taught well and prepared for their futures. And teachers, Pete said, were "DDD. Dedicated, determined and devoted."

Pete herself would go on to earn a doctorate and become the first female principal of South Mountain High School, then the first Black woman deputy superintendent of Phoenix Union High School District.

Another Okemah resident, Geneva Mosley, would become Tempe Elementary School District's first Black teacher. In 2022, the district renamed a school after her.

Geneva Epps Mosley Middle School sits on the southeast corner of University and Priest drives. It was formerly named after a Ku Klux Klan member.

When Okemah kids weren't at school or home studying, they were most likely at church with their family. The Willow Grove Baptist Church was the unofficial home away from home for many in the community.

Former residents say those values still persist today.

They're what caught the attention of Bishop, the ASU film professor. A mother, Bishop said what she learned about Okemah has inspired her daily life. She thinks more about what she's doing to cultivate community and uplift her neighbors because of Okemah.

Tamala Daniels, the descendant of Okemah pioneers and a member of Phoenix's South Mountain Village Planning Committee takes every chance to educate her peers about Phoenix's historic Black community.

"It's very important that I make sure the story of Okemah and original settlers are well known. Because there seems to be this rewriting of history that continues to avoid Black settlers and what we had to endure ... how Black homeownership continues to be impacted, and how the city and state continue to not invest in the infrastructure of south Phoenix," Daniels said.

Taylor Seely covers Phoenix for The Arizona Republic / azcentral.com. Reach her at tseely@arizonarepublic.com or by phone at 480-476-6116.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Okemah: Phoenix's historic Black community torn apart by the freeway