I Was Lost Until I Became a Stoic

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

Each night as I put my three-year-old son to bed we read our books, we sing our songs, and I tell myself that he may not survive to see the morning. When I revealed this to my mother the other night, she said it made her sick to her stomach. “How could you do that?” she asked. “How could you possibly think like that?” She sat on the couch in my living room, the light from the fire roaring in the fireplace danced across her face as she looked at me with earnest concern. I sat on the hearth and took a beat to digest the moment. Then I inhaled deeply, and started to explain.

About two and a half years ago, I became fascinated with the philosophy known as Stoicism, an ancient school of thought that urges us to own the immediate present, and in doing so, to achieve true freedom—and, perhaps, even happiness.

My nighttime ritual, I told my mother, is actually the furthest thing from morbid: It is an affirmation of life. It’s a practice I picked up from one of the Roman Empire’s fabled Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius. (Yes, the same Marcus Aurelius that gets murdered by his son in Gladiator—the irony of which is not lost on me.) In a glut of bad luck that can only be characterized as obscene, Aurelius outlived nine—nine!—of his own children. From a father’s inconceivable heartbreak came wisdom that would span millennia. Borrowing from the philosopher Epictetus, he wrote in his book Meditations, “As you kiss your son good night, whisper to yourself, ‘He may be dead in the morning.’” This thought exercise is not meant to terrify any young parent. Instead it’s to remind them that there will be a last time that you do every single thing that you love—and if you are lucky, you won’t even know it. So make the most of each single precious moment while you can. When I remind myself of Aurelius’s words at night, every song tends to go on for just one more verse, and then one more verse again. Lately, my son and I have been perfecting a harmonized medley of “The Owl and the Pussycat” and “Sugar” by The Horrible Crowes.

Aurelius is perhaps the most famous proponent of Stoicism, a Greco-Roman philosophy born from Zeno of Citium, who lived and taught in Athens circa 300 B.C. If Zeno was DJ Kool Herc, rap’s founder, then Aurelius, who lived some 450 years later, was Biggie Smalls—the man who turned it into something sublime.

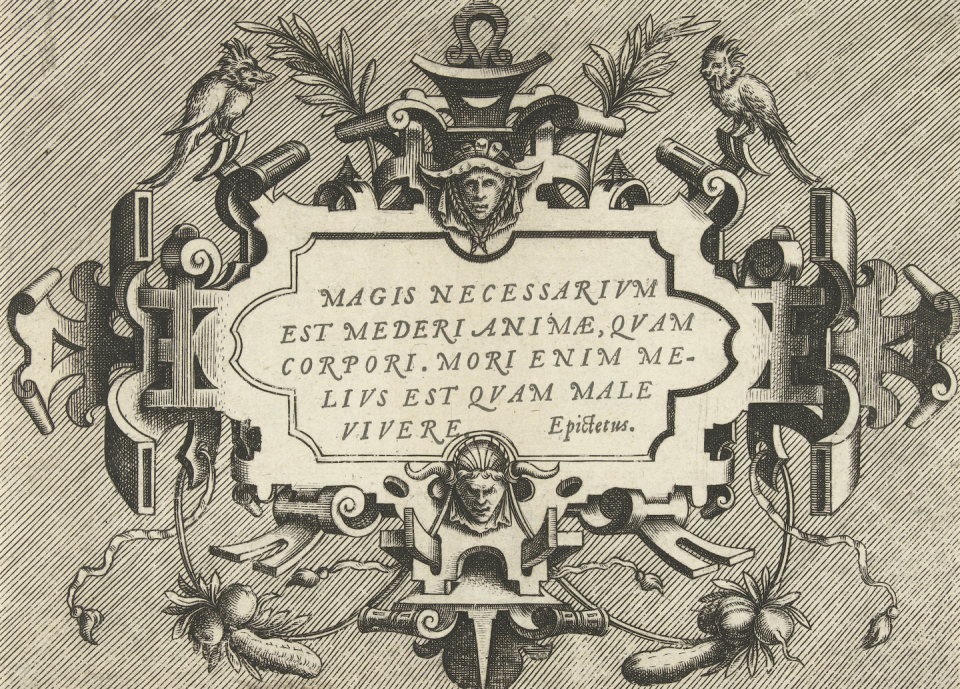

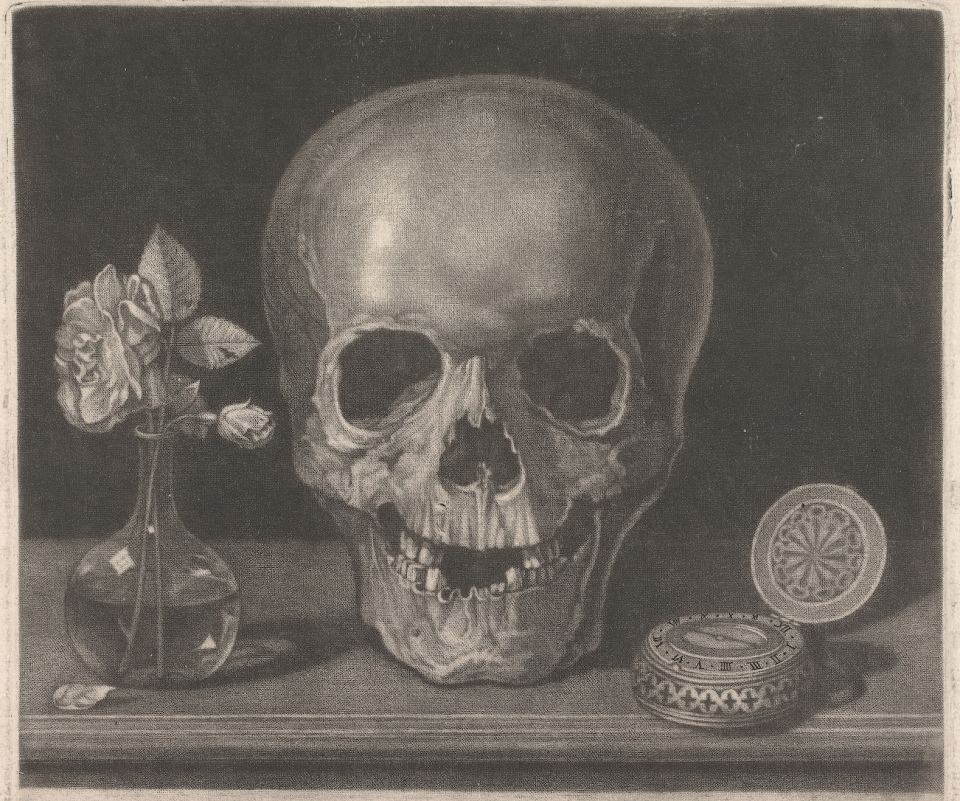

Stoicism first fluttered into my consciousness by chance, through the creations of another rapper, Mac Miller. In his final music video before he overdosed in 2018 at age twenty-six, he lies inside a buried coffin and scratches “Memento Mori” into its lid as a cigarette dangles from his lips. (Now that shit is morbid.) I googled the phrase and found that it is a main tenet of Stoicism. It translates to “remember you must die.” And despite the obvious denotation, it is actually a command to live fully, intentionally, and humbly. Nothing in life is permanent. And a full and clear-eyed account of your mortality on a daily basis chisels the excess clay away from the masterpiece your life can be. Memento mori stuck in my head, but I didn’t give it much more thought for some time.

Then the pandemic hit, and I, like so many others, felt my mental health cratering. I had battled depression for as long as I could remember, dating back to age eleven. As a kid, my outlet had been sports; as I got older, it became workouts so hard that they purified the soul. I found Brazilian jiu jitsu in my mid-thirties, and the sense of community and the unmatched physical exhaustion wrought from grappling for your life was a saving grace. But now, all the gyms were closed. Add in isolation, existential angst from endless doomscrolling, a work environment that even across Zoom felt hostile, and an ever-increasing flow of Jameson whiskey used as an ill-advised salve, and things were looking rather bleak. My marriage struggled mightily—we nearly bottomed out. I began having panic attacks so severe that they were physically crippling. I’d shuffle into the bathroom of my Hoboken apartment so my wife and son wouldn’t see, and then I’d double over on the floor, my eyeballs bouncing from side to side, up and down, uncontrollably, as if I were possessed.

My job at the time was as an editor at a yacht magazine. My chief responsibilities were flying to places with palm trees, getting on a boat, then writing an article about whether I liked said boat. (Yes, that’s a thing you can do for pay.) It was what many would consider a dream job, and I soon left it behind in dramatic fashion.

After that, things really got bad. I began to have dark and cyclical thoughts that latched onto my consciousness, burning and raging there like psychic napalm.

I needed help. More than my friends, family, or therapy could provide. I needed to reset my moral compass, and no one else but me could do it. And this is when I came back in touch with Stoicism—though, to be honest, I can’t recall exactly how. Things were a bit foggy that long, hot, cicada-thick summer.

Stoicism, like most schools of philosophy, is far-reaching and complicated. But it is also both beautiful and notable for its simplicity. I enjoy philosophy, but I’m very much a layman. Sans any PhD hanging on my wall, here is how I can best convey my understanding of it: Your mind creates your reality, and your mind can be trained. Fate exists and is beyond our control. Events both good and bad will unfurl in our lives. And our greatest power resides in the moment we choose how to respond.

Perhaps the Stoic-influenced Austrian psychotherapist Viktor Frankl—whose Holocaust memoir Man’s Search for Meaning should be on every human’s reading list—put it most succinctly: “Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one's attitude in any given set of circumstances.” You could be doing something so banal as sitting in traffic, or getting stuck in a boring dinner conversation. Amor fati, a Stoic would say. Love your fate. This moment could not have ever possibly unfolded any other way than it has right now. And this moment is yours alone, so you must embrace it. You have no other moral option.

When I tell people I subscribe to Stoicism, I hear two main critiques. One is based in the misunderstanding that I mean the adjective, as in “being stoic,” and not the noun, as in “being a Stoic.” To be stoic is to be a stone, impervious to feelings. To be a Stoic is to use reason to leaven our emotions and passions—and then to master them. A life without passion is no life at all. But a life lived enslaved to passion is not much better. Memento vivere, you’ll hear modern-day Stoics say. Remember to live. It’s an important juxtaposition to the pile of bones that memento mori portends. Life is not a drab endurance test. It is a tapestry of pregnant moments bursting with possibility that we are compelled to suck the marrow from.

And that leads to the second criticism I’ve most often heard. A friend of mine—my age, just hit forty, a fellow father and searcher—once told me that he had come across Stoicism, but had spurned it as a possible path for him because, in his words, “I can’t just quit my job and go travel the national parks with my kids. I have a mortgage.” He was, of course, right about that—for the most part. But what he was missing was that Stoicism does not teach carpe diem in the cliched, embroidered-throw-pillow sense. Instead, it demands that diems be carpe’d incrementally. It teaches to soberly decide what is the best course of action in a given moment, exercise that action to its fullest, and trust that the sum of these minute decisions, made again and again and again and again, will result in the best life one can hope to lead.

If any of these principles sound familiar to you, it’s because Stoic-influenced worldviews are enjoying a bit of a Renaissance. All the new wisdom is old wisdom. Journaling as part of a meditative practice is en vogue these days. And Meditations can be thought of as archetypal in this regard—Aurelius wrote it for himself, with no intention of publication. Stoic ideas influenced cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—a popular form of psychotherapy—that teaches patients not to dwell on the past, but to focus on making healthier decisions in the present, thereby creating a better future. The serenity prayer, so helpful for so many in addiction treatment, borrows directly from Stoicism, asking for the grace to accept the things one cannot control, as well as the courage to change the things one can. The secular-humanist philosopher Sam Harris devotes hours to Stoicism on his meditation-focused app, Waking Up—not too shabby for a philosophy that also made an indelible mark on Thomas Aquinas.

Stoicism’s current-day reemergence should not exactly be surprising. The philosophy was born during the Hellenistic period, as Alexander the Great’s empire fractured, and homogenizing factors like shared language and religion became destabilized. The human mind longs for meaning, the heart for community. As the Greek world rapidly changed, Stoicism took root. In modern times, with institutions on a steady decline, combined with technology like social media that so often serves to frighten and divide, it’s a ripe time for the rebirth of an ancient, stabilizing force.

The crisis in Ukraine tests my adopted belief system. On the first night after the invasion, in February, I had a nightmare of being in my home with my family as it was torn apart by mortar fire. The next day felt particularly dark to me, even from half a continent and an entire ocean away. I had déjà vu feelings of the first weeks of the pandemic, when the headlines were apocalyptic, and everyone I spoke to seemed a little scared and very confused. So I decided to start spreading what I'd learned.

I had a call with an editor friend in Brooklyn around noon that first day, ostensibly to discuss future yacht-centric assignments. Instead we ended up talking about the possibility of a nuclear holocaust. Normally a chill guy, he seemed unusually angsty about Ukraine, and I realized as we spoke that he had a son of draft age. My own anxieties vanished as I saw my role to play. I gave him the whole spiel. “Control the things you can,” I said, “And leave the rest alone. Focus on what’s in front of your face. You gotta mend your fences and tend to your garden.” After we got off the phone I sent him a text of Alfred E. Neuman—What, me worry? It’s always hard to tell if a laugh through an SMS bubble is genuine, but I like to think that his was.

That evening, I went to the jiu jitsu gym early and greeted everyone with a fist bump and a smile. I checked in on a Belarusian black belt with family near the border with Ukraine. I grappled my ass off—in stressful times, there is no substitute for searingly hard exercise—and stayed late talking to a kid in his twenties who was having girl problems. He was fixating on his perceived mistakes, some of which happened years earlier. I told him to focus on this moment. “Now!” I slapped the mat. He looked at me and blinked. “Now!” I slapped the mat again. “Right now. Now. Now!” That last time, he slapped the mat with me.

That night, I fell asleep easily and slept heavily, knowing I had no control over the whims of a nuclear-armed Russian madman, but also that I had done my best that day to make the world a little bit gentler for the people in my orbit.

Embracing Stoicism helped me dig out of a hole made mostly of my mind’s creation. I now begin each day with a Stoic meditation (I recommend Ryan Holiday’s The Daily Stoic as a good place to start in this regard) and take care to no longer suffer imagined troubles. Rather, I attempt to embrace my circumstances as a necessary part of my path. People sometimes ask me if there was one grand moment when Stoicism came to my aid. And they’re always a little disappointed, I think, to hear that there was not—instead, and by design, it bolsters me in a million tiny ways. This is not to say I don’t still get pissed off when my Dropbox won’t synch, or keep my cool when my kid won’t stop shouting about something. I sometimes still feel those old, dark depressive thoughts crowding my mind at 3 a.m. like unwelcome strangers sitting next to me at a bar who won’t shut the fuck up. But now I have a plan of attack, a moment within which to breathe, regain perspective, and begin the fight anew. It’s been life-changing. I’m a better version of myself, and one that I probably would not have even recognized just a few short years ago. And perhaps most importantly, I can’t even imagine a regression back to the bad old days.

Through Stoicism one can come to understand how to manage life’s difficulties, real or perceived, with grace, calmness, and reason. Nothing so small as a moment is insurmountable, and moments are all that we have. Should you choose this path, you will come to realize one important fact. You have survived every trial and tribulation that life has thrown at you up until this very instant. When future troubles come—and they will come—a version of you will be born into that moment that can conquer them, too.

Unless, of course, you die. Don’t forget about that part.

You Might Also Like