The louder, the better: the evolution of Al Sharpton

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Early in his career, the Rev. Al Sharpton was painted as the civil rights movement’s court jester. That’s how filmmaker Josh Alexander first saw him. When he was growing up in California, Alexander would come home from school, make a snack and watch the explosive preacher on daytime talk shows like "The Phil Donahue Show" and "The Sally Jessy Raphael Show."

“He was this carnivalesque, almost buffoon-like troublemaker,” Alexander said in a recent interview from his home. “Racially divisive, controversial and loud.” But when Alexander got to college in the 1990s, he learned enough to change his mind about Sharpton. He hopes his new documentary will persuade others to do the same.

"Loudmouth," which has John Legend as one of its executive producers and premiered on BET last weekend, challenges the common narrative about Sharpton. It makes the case that the news media took liberties to present him as a camera hog who came out of nowhere with a mission that had more to do with being a celebrity than a change-maker.

“Local media always had a more rounded view of who I was. They just decided to cast me in a certain way,” said Sharpton, who first saw the entire movie last June at its premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York. “I think that’s one of the themes of the film.”

'I was reckless,' Al Sharpton says

Sharpton chatted about the documentary and his career earlier this winter from a swivel chair in his National Action Network headquarters in New York. For the Zoom interview, he speaks in an even-tempered tone while sporting a gray suit and no tie.

It was in sharp contrast to his image in the ’80s and ’90s, when he was much heavier and favored track suits and medallions around his neck. That look only bolstered the cartoon caricature.

“I was reckless,” he said. “I weighed 300 pounds. I didn’t care that I wore my jogging suit.”

Sharpton started taking better care of himself around 2001. He fasted while serving a 90-day sentence for trespassing on U.S. Navy land during a protest against military bombing exercises in Puerto Rico. During that period, he said, he lost weight and thought about when his youngest daughter, Ashley, asked him why he was so fat. He also reflected on advice from Coretta Scott King, the widow of his idol, Martin Luther King Jr.

“She was the one who said, ‘If you really care about the cause, you have to be careful about what you say and how you appear. People can’t hear your message if they can’t get over your brashness or your appearance,’” he recalls. “That changed my attitude. How do I empower a community if I’m not empowering myself? It made me take myself more seriously.”

"Loudmouth" dedicates considerable time to showing the more mature Sharpton — diligently working with his staff of 51 people at National Action Network to decide which cases to support; preparing for his shows at MSNBC, where he has worked for over a decade; attending his birthday celebration with a guest list that included Sen. Chuck Schumer, former New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo and actor Robert De Niro; and delivering a stirring speech at George Floyd’s funeral.

'I think he's evolved'

It’s that figure whom so many younger civil rights leaders have gotten to know and admire.

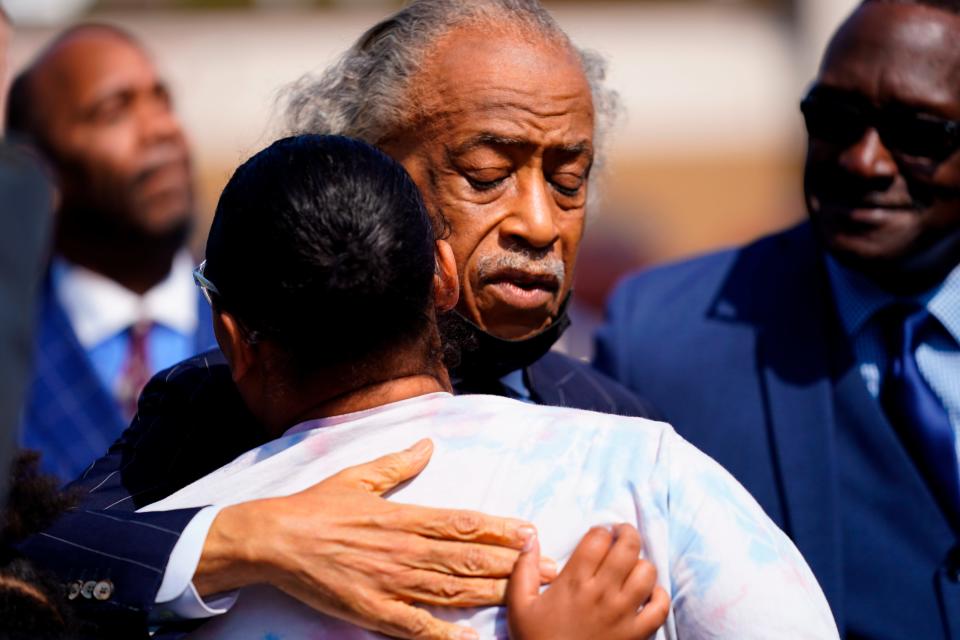

“I think he’s evolved,” said Yohuru Willams, an activist who is director of the Racial Justice Initiative at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, and has been a guest on Sharpton’s MSNBC show, "PoliticsNation." “We often forget our most revered symbols were ministers. We forget that they also bring pastoral care to the table. Yes, he brings the kind of attention that we’re going to win justice, but he also says to families, ‘I’m going to help shepherd you through this difficult moment.’ That tradition, the importance of the Black church, is very important.”

For the documentary, Alexander and his team reviewed roughly 1,200 hours of footage to find moments that showed how Sharpton has earned his place on stage alongside his mentor Jesse Jackson. The film shows Sharpton winning honors as a teenager that led to a friendship with music legend James Brown, making thoughtful appearances on TV programs when he was in his early 20s, and working so many hours he barely had time to go home and change clothes.

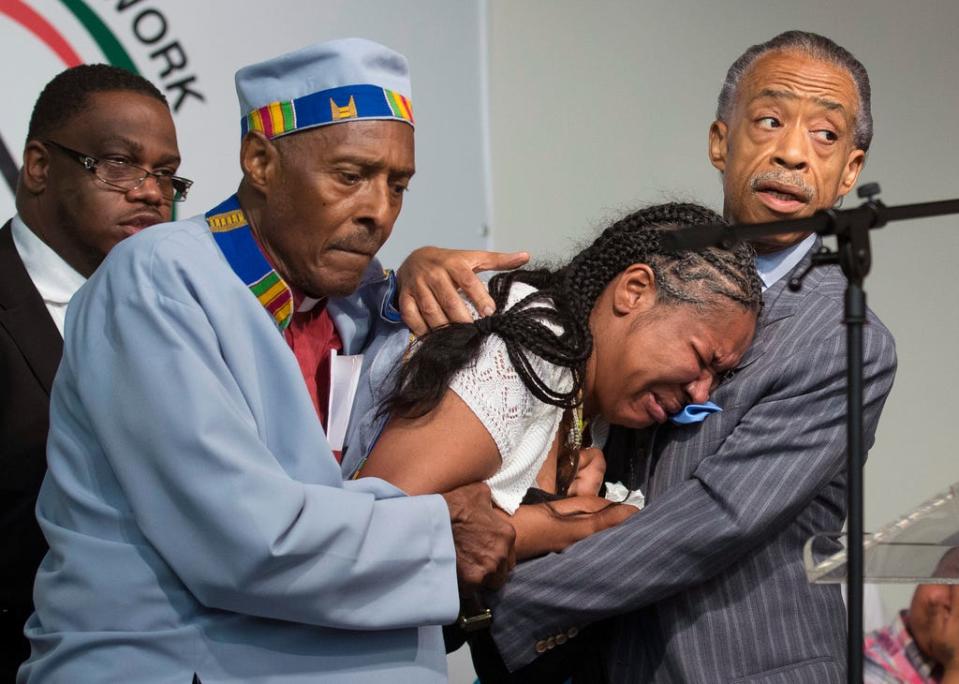

The film also shows his softer side, counseling victims’ families in scenes he usually barred cameras from capturing.

“Most of his ministry has never been shown to press and reporters,” Alexander said. “He sees it as a deeply sacred, private thing. If he did allow (media coverage), people might view him differently. But he’s drawn a line.”

Critics knock 'ambulance chasers at times of racial trauma. But they show up'

Sharpton, 68, was surprised by some of the footage Alexander unearthed for the film, some of which he had never seen because news stations never aired it.

"Loudmouth" doesn’t ignore Sharpton’s more explosive chapters, which include hisleading protests in New York City after the racially motivated 1986 killing of a young Black man and the beating of another for driving through the white area of Howard Beach; marching through Bensonhurst, Brooklyn, in 1989 after the killing of 16-year-old Yusuf Hawkins, who had gone to the area to buy a used car; and leading a march after the death in 1991 of 7-year-old Gavin Cato, who was hit by a Hasidic resident who lost control of his car while speeding in Crown Heights, Brooklyn — which further strained relationships between Black and Jewish communities.

The film also shows scenes of Sharpton defending 15-year-old Tawana Brawley in 1987. Brawley alleged that she had been kidnapped and raped by a group of white men. A seven-month grand jury investigation concluded she had lied.

These are the moments that earned him his fiery reputation — and inspired the film’s title.

Williams believes some of the showboating was beneficial. “The critique of Rev. Sharpton and others like him is that they’re ambulance chasers in times of racial trauma. But they show up,” he said. “They’re able to marshal interest through their celebrity and get media attention. The knock is that once the attention dies down, they are on to the next site of trauma. But you kind of need that in a national organization.”

Sharpton: 'Nobody calls me to keep a secret'

Sharpton, who had no editorial control of the film, has no problem with the title.

“People said, ‘They’re mocking you.’ I said, ‘You don’t understand,’” said Sharpton, who sat for three days of interviews with Alexander.

“Unlike King, I wasn’t born in Atlanta, or Jesse Jackson who was raised in South Carolina,” Sharpton said. “I was born and raised in New York, where you are competing with Broadway lights and the Statue of Liberty. You had to be loud to make your issues heard. There were people protesting racial violence and police brutality before me, but they couldn’t arrest the attention. With the combination of being a boy preacher and the theatrics of James Brown, I was able to conjure up what they couldn’t ignore.”

During his eulogy at the Minneapolis funeral for George Floyd in 2020, Sharpton acknowledged that he sought out attention. “Well, that’s exactly what I want. ’Cause nobody calls me to keep a secret. People call me to blow up issues that nobody else would deal with. I’m the blow-up man, and I don’t apologize for that.”

Sharpton, who ran for president in 2004, said he doesn’t regret any of the decisions he’s made over the years, but he admits he could have handled certain situations with more diplomacy. He eventually learned that tactics shouldn’t be driven by emotion, that shooting from the hip can be dangerous.

The primary lesson he said he’s learned: Don’t let your anger and vanity outrun your sanity.

He said he plans to step down as the leader of the National Action Network in the next few years but will still be part of the movement. He wants to build a civil rights museum in Harlem that will spotlight injustice in the North, toward Blacks but also women and the gay community.

“I used to like to go to fights,” he said. “You might start a 10-round fight and get in trouble in the third or fourth round, but if you get through that, you can still win the fight. I went through some rough battles, but I thank God I lasted long enough, not only for people to accept me, but see what I was fighting for.”

Laid to rest: 'I'd be honored': Rev. Al Sharpton to give eulogy at Tyre Nichols' funeral in Memphis

Al Sharpton documentary: Tribeca Film Festival closes out with 'Loudmouth,' John Legend and Spike Lee attend

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Black History Month 2023: The evolution of 'Loudmouth' Al Sharpton