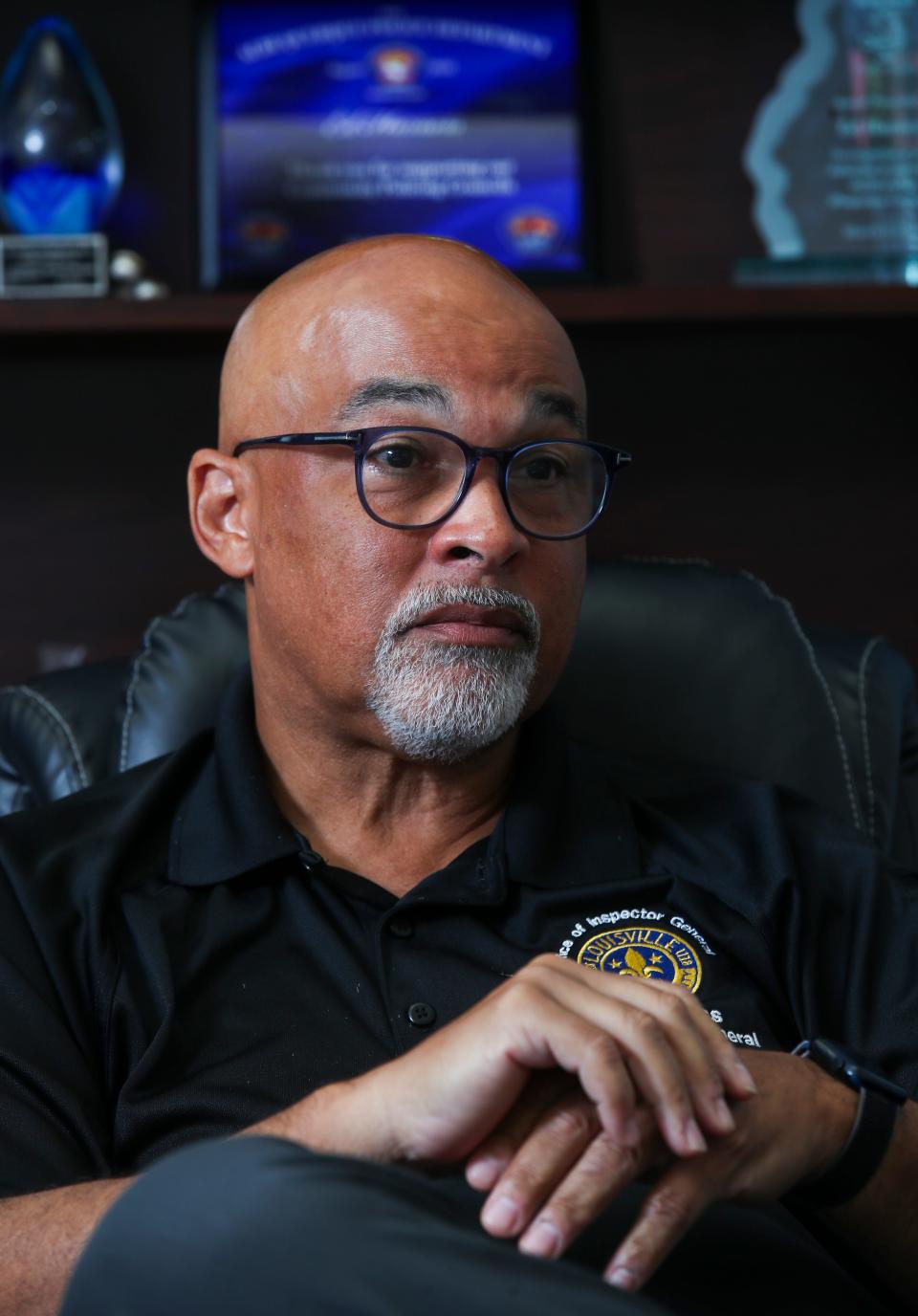

How Louisville Inspector General Ed Harness got on the path of policing the police

For much of the time Inspector General Ed Harness has been in Louisville, he hasn’t been able to do his job.

A Louisville ordinance, passed in the wake of the 2020 police killing of Breonna Taylor, aimed to increase civilian oversight of Louisville Metro Police. As a result, Harness, 63, was tasked with investigating complaints of police misconduct.

But since his office became operational last year, the former Milwaukee cop has faced a litany of roadblocks, from LMPD refusing open access to body cam footage and documents to officers declining to participate in investigation interviews.

“I have been surprised by the level of resistance,” Harness told The Courier Journal in a recent interview. “Some of it is sort of a lack of acceptance ― in that, somehow, if we’re obstructed enough, somehow we’re going to go away.”

An agreement brokered by Mayor Craig Greenberg's administration in March fixed those initial issues. But by June, investigations were again temporarily halted after the union representing police officers filed a grievance.

The monthly Civilian Review and Accountability Board meetings Harness presides over in Metro Hall receive little public attention. But the IG and the board that authorizes his investigations occupy a critical role in the city as it awaits a federal consent decree following the Department of Justice's damning March report on unconstitutional policing by LMPD.

And with the DOJ critical of the limited power of civilian oversight in Louisville — and recommending improving its capabilities — it is likely the consent decree will contain provisions related to oversight.

More on police review board: After DOJ report, Greenberg announces LMPD will cooperate with police review board

A background in law enforcement

As a young man, Harness wanted to play professional baseball. And in his telling, baseball is the only reason he went to Cal Poly Pomona in his native California.

But a broken hand — and a fallout with a coach once it healed — would sideline him in his junior year.

“Baseball wasn’t looking good, and I wasn’t really enthusiastic about being in school,” he said. “So, I went into the army.”

These days, he has a Louisville Slugger bat sitting on his desk and drops baseball terminology into conversations about police accountability.

The decision to drop out of college would set him on a trajectory toward a career in police accountability.

In the Army, he served as a military police officer for six years.

Later, after leaving the military, he moved to Milwaukee, where he joined that city’s police force in 1991.

More on DOJ report: US DOJ's report on Louisville police: Read the violations and recommended reform

In Milwaukee, he had an on-foot patrol and saw policing done right.

“We were very much the community-oriented policing model in Milwaukee,” he said. “We were encouraged to counsel, we were encouraged to take time. If we had to go to repeated calls — like for neighbor disputes and things like that — we would be encouraged to mediate the situation, so that you could reduce your calls for service for addresses.”

Harness said he twice found himself in situations where deadly force would have been authorized but where he did not use it, instead turning to de-escalation and pepper spray when confronted with people armed with knives.

Lessons in police oversight

As a cop, Harness continued pursuing his bachelor’s degree, finally getting it 19 years after enrolling in college. With his degree in hand, he left the Milwaukee Police Department to go to law school, graduating in 2000.

After several years of private practice, an opportunity came up to be a volunteer police commissioner in Whitefish Bay, an affluent community of about 15,000 people on the shores of Lake Michigan, seven miles north of Milwaukee.

The police commission had a level of civilian oversight power unheard of in Louisville, with the final say over all police hiring and promotion decisions.

Frustrated with his law practice and interested in a bigger role in police oversight amid the renewed national focus on reform following the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, Harness applied to three big city oversight jobs, ultimately landing one in Albuquerque, New Mexico, leading the city's Civilian Police Oversight Agency.

New Mexico’s largest city had come under a federal consent decree in 2014, the year before Harness arrived, after a DOJ investigation found the Albuquerque Police Department practiced unconstitutional policing and used excessive force.

Albuquerque had oversight for decades, but the DOJ found it insufficient, determining in its investigation that Harness’s predecessor was “more closely aligned with the [police] department than with the community” and had “failed to find violations of department policy in cases where it is more likely than not that violations occurred.”

In Albuquerque, Harness got a crash course in consent decrees and the complexities of police reform that would prepare him for Louisville.

"I think it's been a success," Harness said of Albuquerque's consent decree. "It took longer than it should have — part of that was the leadership of the Albuquerque Police Department, for the first couple of years, was really obstructing the work of the [federal] monitor."

'Level of arrogance' within LMPD

In late 2021, Harness arrived in Louisville, where public trust in the police department remained low following the killing of Taylor and months of protests that followed.

It was also a department under DOJ investigation — though on ride-alongs with LMPD officers, Harness was shocked to learn some were unaware of the federal probe.

He has also felt higher ups are not taking the problems seriously.

“There’s a level of arrogance within the department that they still aren’t grasping the problem,” he said. “And I’ve been surprised at the lack of contrition that I’ve seen when I’ve met with the command staff. There will be some acknowledgement that we should exist, but ‘is it really that bad?’”

After more than a year and a half in Louisville, his conclusion is that LMPD is unprepared for a consent decree, despite public assurances from LMPD’s chief and Louisville’s mayor that reform is underway.

“I think the biggest challenge in Louisville is that the department is not prepared for how much policing is going to change for them in their daily lives,” he said. “I don’t think they understand all the changes that are going to take place. Every city that’s been under a consent decree believes they can somehow prevent it or make it less impactful.”

Reach reporter Josh Wood at jwood@courier-journal.com or on Twitter at @JWoodJourno

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Meet Louisville's outspoken police oversight czar Ed Harness