Louisville stood by as thousands of kids were poisoned by lead paint. Is hope on the horizon?

Editor’s note: “A Heavy Burden” is a five-part investigation into Louisville’s ongoing problem with childhood exposure to lead paint. What is often thought to be a 20th century problem is still very real in 2023. Nearly 10,000 local children tested with high lead levels in their blood over the past two decades, and kids are still at risk today. A new law, still a year away from implementation, aims to right this wrong.

Over the past two decades, thousands of Louisville children have tested with elevated levels of lead, poisoning their brains, sequestering in their bones and endangering their futures.

The neurotoxin inhibits children’s brains in key areas, threatening cognitive development, decision-making ability, learning and behavior. Its victims struggle in school, score lower on tests, and may incur higher costs for special education programs or, eventually, the justice system.

And while some U.S. cities implemented legislation in recent decades to proactively combat childhood lead poisoning — creating frameworks to search for lead paint in homes before children are poisoned — Louisville waited.

In an investigation spanning five months, The Courier Journal found:

A lack of local and state regulations has left children defenseless to a potent neurotoxin, with untold consequences for their educational attainment and later life outcomes;

Prior to the passage of a new Louisville law to address the issue of lead paint, local real estate interests lobbied to strip key protections from the proposal;

After the law's unanimous passage by Metro Council, at least one real estate group was working behind the scenes to delay or loosen the law;

Blood lead level testing for Jefferson County children declined by nearly 80% from 2006-20;

Lead exposure in Louisville is in line with a long pattern of systemic housing and environmental injustice, with West End children more than nine times as likely to be poisoned, by one estimate.

And earlier this year, when the U.S. Department of Justice published its scathing investigation of Louisville’s policing practices — including findings of discrimination “against people with behavioral health disabilities” — the report also highlighted the city’s staggering disparity in childhood lead exposure west of Ninth Street.

In some cases, Louisville children are testing with elevated lead levels for years at a time, with public health officials lacking the resources to promptly investigate the source of their exposure, according to Julia Richerson, a veteran pediatrician in the South End.

While the families wait for answers, the neurotoxin tightens its grip.

“We should not be sleeping at night,” Richerson said. “I don’t.”

Public outcry over lead paint peaked in the 20th century, but through dozens of interviews with pediatricians, parents, researchers and educators, The Courier Journal found childhood lead exposure at the intersection of some of Louisville’s most contemporary challenges: education, crime, housing, health care and food access.

The issue of childhood lead poisoning “has kind of fallen on the back burner” in Louisville, said Ashley Brandt, director of early care and education at Metro United Way. “The inability to wrap our arms around it is a horrible excuse.”

For decades, “you could have a home covered in lead paint, you could have windowsills covered in lead paint, lead dust in the house, and know about it, and you could rent that to a family of five,” said Brian Guinn, an epidemiology researcher at the University of Louisville.

“There was no issue with that, legally.”

Then, last year, Metro Council unanimously approved a landmark ordinance requiring property owners to remedy lead hazards before leasing. It was lauded by both sides of the aisle as a thorough, collaborative effort to satisfy both child health advocates and real estate stakeholders, and make headway where protections have long been lacking.

But records obtained by The Courier Journal show some real estate interests were still pushing to weaken the law just weeks before it passed. And now, one year before the ordinance takes effect, another group has raised concerns about implementation of the new rules, arguing a lack of specifics could hurt small property owners.

An invisible problem

In Kwmisha Adams’ century-old rental in Shawnee, “everything is falling apart.”

On rainy days, her porous basement walls “cry,” she said. The window frame in her child’s bedroom easily falls out of the wall. When she told her previous landlord of the rodent problem, she was advised to get a cat.

In recent months, Adams has juggled work, parenting five children, and her own case of Bell’s palsy. Her car has broken down, she’s struggled to keep up with her utility bills, and she narrowly escaped eviction in November after a mix-up between the Section 8 voucher program and her new landlord resulted in months of unpaid rent.

“My plate is very full,” Adams said, “and it’s heavy.”

Then, in August, she found lead paint in her home of three years, flaking off of the windowsill above her kitchen sink, where she prepares food for her young children. And again, lining the frame of her front door.

Staff from the Department of Public Health and Wellness visited and confirmed her findings and then some, Adams said.

“It's been on my mind a lot, actually,” she said in an interview two months after the findings.

Adams did some reading about lead, and was concerned by some of the potential health impacts of exposure. She wasn’t sure whether any of her children had been tested for lead exposure, but intended to talk with their pediatrician about it, as well as her landlord.

Chips of lead paint taste sweet, and are especially hazardous to crawling young children, who naturally explore the world with their mouths as a part of normal cognitive development. Even invisible lead dust, which may be produced by the repeated friction of opening and closing windows and doors, is an airborne hazard.

Adams’ five children range from 6 months to 11 years old. She described them as smart, talented and “courageous,” and she wants better for them.

“I know that I’m not capable of giving them the life that they deserve, or need,” Adams said. “I need a break. I need to be stable somewhere, you know. Stable, at least.”

Adams is entirely absorbed with working to pay the bills, putting food on the table and meeting her family’s basic needs. That doesn’t leave much time or energy to spare searching for an invisible poison in her walls, or addressing it herself.

Because of the scarcity and dilapidation of Louisville’s affordable housing stock, she’s facing an impossible choice: unsafe housing, or no housing at all.

‘A classic social justice issue’

After finding lead in her own home, Adams took a testing kit next door and found it on her neighbor’s porch, too. Several other homes on her street display the same “alligator-scale” pattern of chipping often seen in aging lead-based paints.

An estimated 89% of homes in the census tract where Adams lives were built before 1960, according to federal data, placing it in the 98th percentile nationally.

In the 20th century, lead paint was considered the gold standard for its durable and quick-drying quality.

Anne Dages Nutt, third-generation owner of Louisville-based Dages Paint Co., recalled a time when an advertisement for lead-based paint filled the entire front window of her family’s store. Ahead of its national ban in 1978, customers came in and bought lead paint in droves, stockpiling it before federal law took it off the shelves for good, she said.

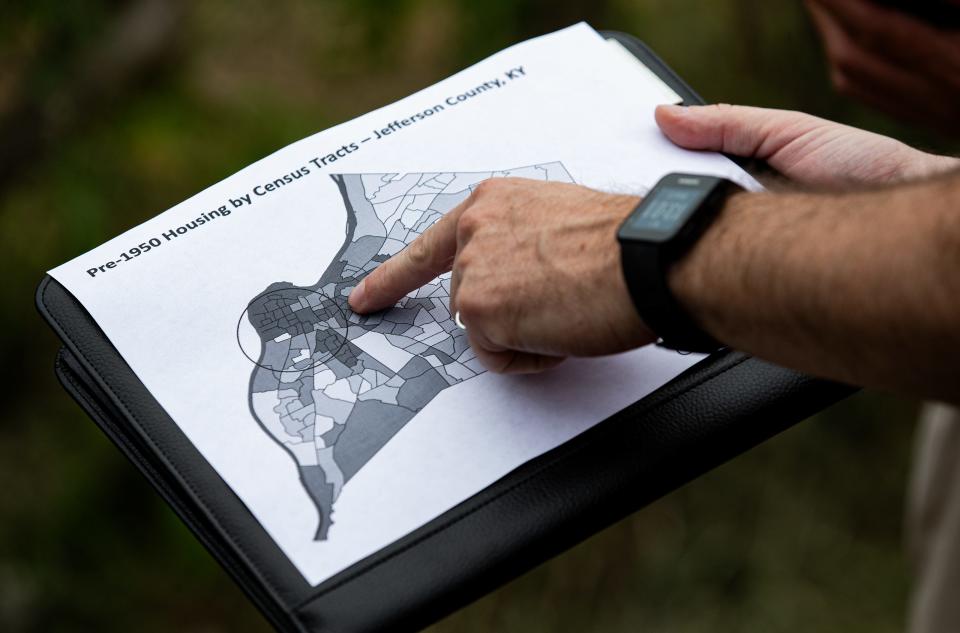

In Jefferson County alone, there are tens of thousands of housing units built, and painted, before the 1978 ban. And in the U.S., lead-based paint dust remains the most common route of exposure, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

“It's not in the news. It's not sensational,” said Nicholas Herring, a graduate student who’s helped Guinn with his local research into the issue. “It's a little more insidious, because people don't know it's there.”

And decades after its national ban, the toxic paint is still chipping from door frames in Shawnee and from windowsills in the Highlands.

Lead “is an equal opportunity poison,” said John Cullen, whose Louisville-based company sells products to detect lead and reduce its absorption into the body. A former landlord now deep in the lead poisoning prevention business, he’s seen childhood exposures reach families “in some of the most expensive real estate in town.”

But Louisville’s deep-rooted wealth disparities amplify the burden in neighborhoods like Adams’ in the West End, where families are less equipped to combat lead, and where redlining and other systemic issues have created a pattern of low-quality, often unsafe housing in today’s majority-Black communities.

Children in northwest Jefferson County face a risk of lead poisoning more than nine times higher than children who live elsewhere in the county, based on Guinn’s analysis of elevated blood lead level cases.

Part 2: Real estate groups pushed to delay, weaken Louisville's new lead paint law.

“I think this is a classic social justice issue, right?” said Richerson, the South End pediatrician. “The people that are most impacted are currently dehumanized by our society already.”

Guinn has also taken paint and soil samples from dozens of abandoned properties around the West End, and consistently found both at levels many times higher than EPA guidelines. Lead has been deposited in Louisville’s soil over decades of leaded gasoline use, coal power plant emissions and from rain, over time, washing aging lead paint off structures.

And it’s not uncommon, Guinn said, for kids to play in the yards of these abandoned properties. On some of his sampling visits, he’s found children’s toys left behind.

Lead targets what ‘makes us uniquely human’

Cory Wallace works at Dages Paint Co., where distraught parents sometimes come in, looking for help confronting a discovery of lead paint in their homes, or in their child’s blood.

More than 30 years ago, one of those children was a close relative to Wallace.

Only 1 or 2 years old at the time, the child had a high exposure to lead paint in their childhood home off William Street in Clifton.

Wallace described the child's arduous treatment and recovery — likely by chelation therapy, a blunt tool for removing heavy metals from the body reserved for extreme cases of lead poisoning because of the risk for complications.

The only safe level of lead in the body is zero, and even low levels of exposure, as seen in thousands of Louisville children in recent years, can plague the developing brain.

The neurotoxin targets the hippocampus, key to learning, and where the brain stores long-term memories. It attacks the cerebellum, traditionally associated with balance and motor skills, but increasingly recognized for its role in emotional regulation, language and other key cognitive functions.

Lead also besieges a child’s developing prefrontal cortex — “the ‘Personality center’ … the cortical region that makes us uniquely human,” according to one neuroanatomy paper.

Lead’s harm to the young brain and the resulting effects on decision-making, learning ability and behavior have been documented for decades. Herbert Needleman, whose research in the 1970s found even low levels of childhood lead exposure can reduce IQ and affect attention span and behavior, put it this way:

“Lead is a brain poison that interferes with the ability to restrain impulses. It's a life experience which gets into biology and increases a child's risk for doing bad things.”

The damage dealt by lead poisoning is lifelong and irreparable, remaining even after blood lead levels have fallen. That’s especially troubling for pediatricians like Richerson, who have seen some of their young patients test with elevated lead levels for years at a time.

And students coming from less privileged socioeconomic backgrounds already face myriad challenges in education. Lead poisoning, with its chokehold on parts of the brain vital to learning, can add a formidable hurdle.

“We have sort of a philosophical belief that all students can learn, and all students can be successful. And I think teachers believe that,” said Brent McKim, president of the Jefferson County Teachers Association and a longtime educator. “And at the same time, I think environmental factors, like lead, certainly interfere with an equitable opportunity to learn.”

Decades of lead poisoning research point to dire implications for early childhood education, including reading ability — a benchmark Kentucky students are struggling to meet in large numbers.

Part 3: Louisville's lead-poisoned children are neglected as testing plummets by 80%

And as any educator will tell you, the early years are critical.

“Students that continue to have behavior issues or learning disabilities … that often goes with them through school, and they need those supports,” said Kim Chevalier, chief of exceptional child education for Jefferson County Public Schools. “As they move into middle school and high school, you know, as they go out into the community and find jobs, it's difficult for them.

“So finding early interventions at preschool is the way to go,” she said. “That's what we need to do.”

The district has increased spending on its special education programs, and has hired 10 Board Certified Behavior Analysts in recent years to accommodate an increasing number of students who need the support.

Drawing direct connections from childhood lead exposure to specific learning disabilities, or even later life outcomes like educational attainment or incarceration, is often impossible.

But lead poisoning is certainly “one more brick in the backpack,” Guinn said.

And childhood lead poisoning prevention is already considered a form of violence prevention in some communities.

“There are a handful of approaches that city governments have access to, to decrease violence without getting into gun laws,” said Dr. Kyle Fischer, an emergency physician with the University of Maryland School of Medicine and policy director for the Health Alliance For Violence Intervention. “Lead is one idea.”

Maryland already maintains a statewide lead law and lead rental registry, requiring pre-1978 properties to register annually, with inspection and lead risk information made available to the public.

As Louisville policymakers discussed an ordinance to reduce childhood lead exposure in rental units, staff from the city’s Center for Health Equity cited research indicating each case of childhood lead exposure could cost taxpayers, on average, $50,000 in lifetime education and crime reduction costs.

Part 4: 'Not a level playing field': Why some Louisville areas are at a higher risk of lead poisoning

By that math, just for the nearly 10,000 cases Guinn documented between 2005-21, lead exposure could have levied a price of about $500 million on Louisville taxpayers.

“This is not just something that is stealing our children's future and stealing their opportunities,” former Metro Councilwoman Cassie Chambers Armstrong said in a committee meeting on the issue last year. “It is also taking our tax dollars, because we have to spend on increased health care costs, increased criminal justice system costs, the cost of that lost educational opportunity, and it's something that is a real cost to our city.”

For many years, other communities have had policies in place to prevent childhood lead poisoning, from New York to Michigan and Maryland. Now, Louisville has its own, and implementation of the new rules is around the corner.

Louisville passes a historic lead law

In the early 2000s, Ralph Spezio, principal of an elementary school in an impoverished neighborhood of Rochester, New York, noted a rash of behavioral issues among the student body.

“Mr. Spezio was very concerned with some of the behavior of the children that were in the school, and he was trying to connect the dots as to why this is happening,” said Albert Algarin, coordinator for Rochester's lead paint program. “He was able to speak with a lot of pediatricians, and they started talking to him about lead poisoning.”

Many of the children with behavioral problems came back with elevated blood lead levels, “and that's when the conversation really started to pick up and snowball in the city of Rochester,” Algarin said.

With community advocacy from the local Coalition to Prevent Lead Poisoning, by 2005, Rochester had passed a pioneering local ordinance, requiring an inspection for deteriorating paint in all rental units before leasing. The city saw rates of childhood lead exposure fall significantly faster than the state overall.

But over the following 16 years in Louisville, without a similarly proactive policy on lead paint hazards, more than 9,800 children tested with elevated blood lead levels, according to Guinn’s analysis of local testing data. Thousands of additional cases are likely missing from that data, he said, because of a downturn in testing over the past decade.

Then, last year, Louisville Metro Council unanimously approved an ordinance modeled after Rochester's, a city of similar size.

Chambers Armstrong, now a state senator but then representing District 8 in Metro Council, spearheaded the legislation, holding numerous stakeholder meetings throughout the year to weigh concerns and gather suggested language from real estate interests and other advocacy groups. Her former district, in the Highlands area, is dotted with old homes.

Over the course of the year, real estate lobbyists sought to strip away key provisions of the ordinance, limiting its purview to housing units where a child had already been exposed to lead, rather than creating proactive policy to prevent those exposures, emails obtained by The Courier Journal showed.

Some revisions were made to loosen the ordinance, and broaden exemptions for the real estate industry. But Chambers Armstrong denied major changes that would have gutted the law's proactive elements.

And the resulting ordinance, approved unanimously, still provides far more protection against lead hazards than anything before it, requiring all of Louisville’s non-exempt rental properties — likely in the tens of thousands — to be regularly inspected for lead hazards before occupancy.

In short, it’s an opportunity for Louisville to catch many of its lead poisoning cases before they happen.

The law takes effect in December 2024. Implementation will take an orchestrated effort by property owners and multiple arms of local government.

Part 5: '100% preventable': Louisville has a path to end childhood lead exposure

And long after the ordinance was approved, real estate interests are still calling the implementation process into question.

Earlier this year, the Kentuckiana Real Estate Investors Association approached several new members of Metro Council who were not part of last year’s debates on the ordinance, gauging interest in revising or delaying implementation of the new rules.

Will Carle, the association’s lobbyist, sees an ordinance “that, in spirit, is right,” he said, and agrees property owners have a responsibility to ensure rental units are safe for families.

But he has also raised concerns about a lack of specifics regarding implementation and enforcement of the new rules, the costs of remediating lead hazards and whether discovery of those lead hazards across Louisville’s older housing stock could create a crisis of displacement in an already meager housing market.

Those costs could vary widely from one housing unit to another, but advocates of the ordinance, including Chambers Armstrong, said landlords should not expect unreasonably high costs of compliance, based on the rollout of similar laws in other cities.

And proponents have stood by remediation efforts as a moral obligation of the real estate industry.

"If your business depends on poisoning families,” Cullen said, “maybe you don't really have a business.”

Read the next story: Real estate groups pushed to delay, weaken Louisville's new lead paint law.

How we did it: A look at the Courier Journal investigation into lead paint

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Lead paint poisoned Louisville kids for years. What's being done now?