Louisville volunteer has vaccinated people, debunked COVID-19 myths for more than a year

With one movement, Oluwasegun Abe pushed a needle into his patient’s left arm, injected him with a dose of the Pfizer vaccine, then quickly replaced the needle with a bandage.

“Move your arm around,” he told Eli Muhammad, an art undergraduate student who was at Shawnee Community Center on a recent day to get his COVID-19 booster shot.

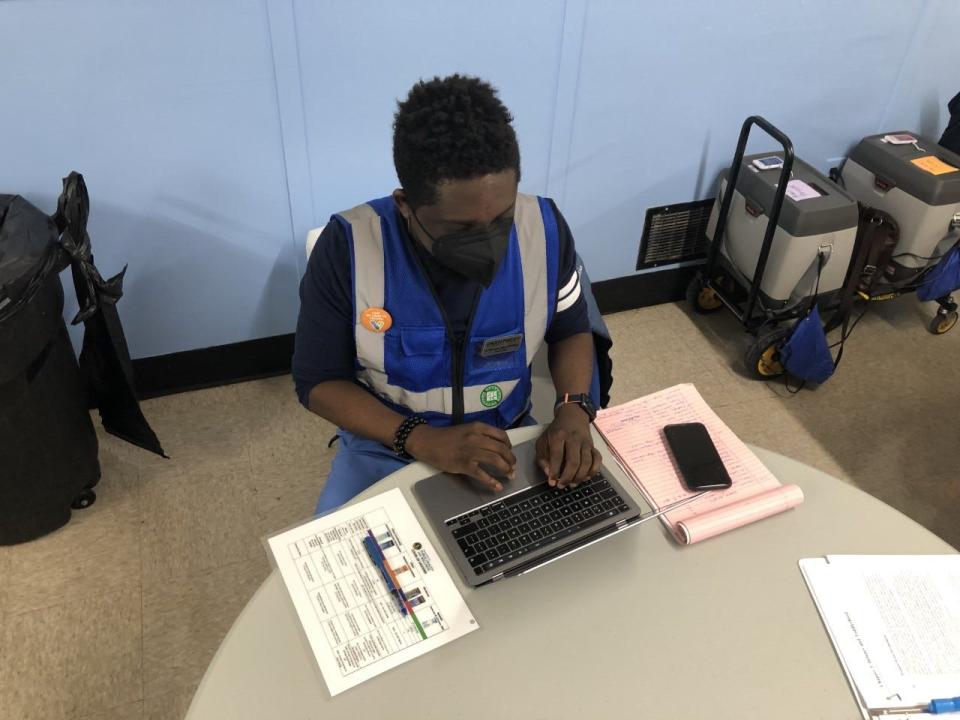

Abe sent his patient to a row of chairs and told him to wait 15 minutes before leaving. Then, he went back to his paperwork while waiting for the next person to drift into the temporary clinic.

The Louisville nurse practitioner works an average of 15 hours a day.

He's up early to see his routine patients at Pearl Medical in Buechel most days. Then, two or three days a week, he heads out in the afternoon to volunteer his time as a Kentucky Nurses Association vaccinator for the city's LouVax sites.

There, he vaccinates whoever is willing against COVID-19. He has conversations with those who aren't yet ready. He debunks the myths they've read online — including the false claims that vaccines contain microchips; that the vaccines are a mark of the antichrist; and that vaccines are a sort of population control.

Sometimes, he said, people come into the LouVax sites just to ask questions. He has to stay up-to-date on enough information to answer just about any vaccine question imaginable. He tells people to bring him anything they've read on the internet about vaccines and he'll go over it with them. He'll either show them how it's incorrect or how it's right.

He's run into people who are hostile toward the idea of vaccination, even rude to him. He said he realizes that every person's concern or fear is very real to them, and he looks for ways to connect so he can unpack any misconceptions or falsehoods they have heard or believe. Sometimes, he has to walk away from those conversations.

"At first it … hurt," he said. "Then I realized that this is beyond me. When a battle is beyond you, you don't take it personal."

Abe estimates he's vaccinated at least 300 people during the last year through his volunteer work. And he plans to keep at it.

"You cannot be tired," he said, "when you think about people dying… There's a personal strength to saying 'I can't retire now, I just have to keep going.' Hopefully this is over soon, hopefully."

More: These Kentuckians hesitated to get the COVID-19 vaccine. Why they finally got the shot

'I'm going to do something to contribute'

As a young child in Nigeria, Abe watched his grandmother, Felicia, suffer from gall stones. Her operation did not go well, he said, leaving her to become septic and suffer liver failure. She died about a year later.

The experience was painful.

"I made up my mind at that point that 'I'm going to do something to contribute to medicine in some way, shape or form,'" Abe said.

He came to Louisville about 14 years ago and studied to become a nurse practitioner focused on family medicine.

When the coronavirus pandemic hit in 2020, Abe said, a lot of his patients in nursing homes died despite his best efforts to save them.

"There was no vaccination. Nobody ever really knew how to treat them," he said. "I did come up with a concoction of medications that helped … but a lot of them died."

It hit him hard.

"I do see my grandmother in a … lot of patients actually," he said.

More: 'It's never going to be the same': Kentucky's 10,000 COVID deaths leave trail of heartache

So when the COVID-19 vaccines got the green light both federally and from local health experts, Abe got busy researching the shots for himself.

Then, he signed up to help the city talk to people about the vaccines and get the shots to everyone he could.

"It meant a lot to me to actually be part of the movement moving this forward," he said. "Immediately, (the vaccine) came with seeing better numbers: less death, less everything. So that was my motivation right there: That the fact that people were old, don't mean they have to die."

And, he said: "There's so much potential in young people for them to die of something that is so preventable."

You may like: Thousands of volunteers are 'the heart and soul' of Broadbent Arena's vaccination efforts

More on COVID: 'Breakthrough' cases of COVID-19 still affecting some who are vaccinated. Here's why

'I have gotten it … And I'm OK'

Beyond general misinformation, Abe said, he looks for ways to break through historical distrust of the health care system and health officials.

Medical researchers and providers withheld treatment from about 400 Black men in Tuskegee, Alabama, from 1932 to 1972 in order to study the course of untreated syphilis, for example.

The experiment led to mistrust of the medical community that experts have said continues today.

"I feel like my presence as a Black person can be important sometimes," Abe said. He can tell people: "'I have gotten it… And I'm OK.'…Hopefully they can believe me enough to say that I'm a good representation of the culture … that I will not give to them what I think is bad for them."

He proudly wears a pin that says "I got my COVID-19 vaccine" on his Kentucky Nurses Association fleece and shows it to anyone he can. He's noticed a shift in some people's attitudes, he said, after he tells them he's gotten his shots.

Vaccine story: Louisville's West End/East End vaccine gap is shrinking. But progress has been slow

Sometimes it strikes Abe that he's a part of a massive historical effort to protect people from COVID-19 and end the worldwide pandemic. But he tries not to think about that.

"I just got to do my part," he said. "I sleep easier when I know that one more person has gotten vaccinated today."

More: He was born prematurely as his dad lay dying of COVID-19. Now, he faces a new struggle.

Reach health reporter Sarah Ladd at sladd@courier-journal.com. Follow her on Twitter at @ladd_sarah.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Louisville volunteer gives COVID shots, debunks myths