Has our love of springs become a fatal attraction?

For thousands of years, the lure of Florida’s springs has been irresistible to people. For me, jumping into the ice-cold water always makes me feel like a kid again.

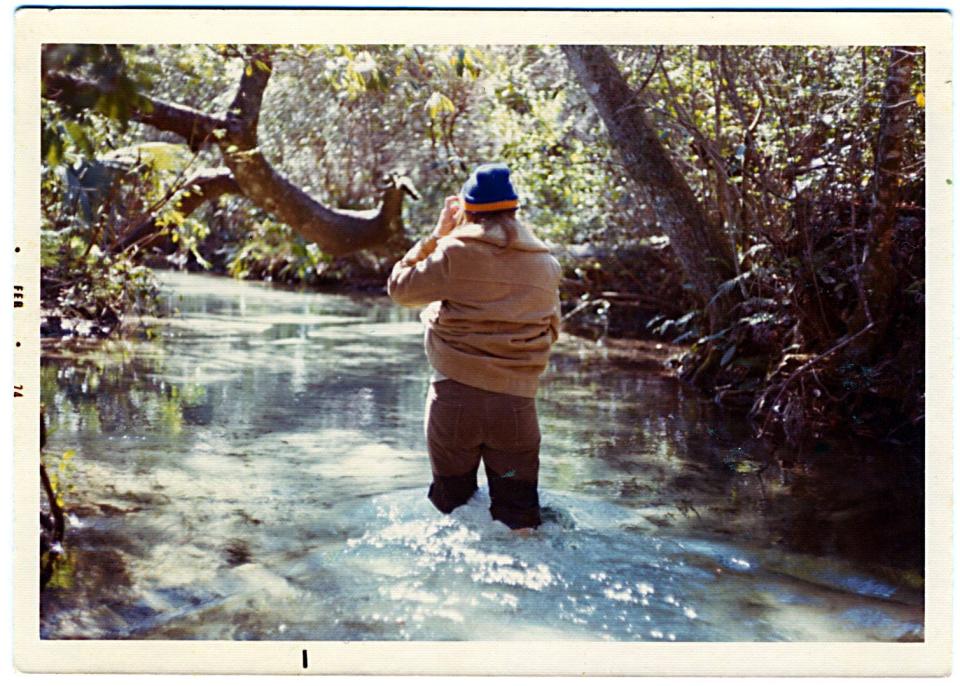

Years ago, a camping trip at a spring along the Santa Fe River was the high point of my Cub Scout experience. The spring was our private thrill ride. We jumped into the headspring with a raft and jetted down the run to the river, where we swam to shore and ran back to the headspring to do it again.

It was an exhilarating experience, better than any theme park ride, with no waiting in line and no crowd — a far cry from the estimated 30,000 people who visited Ginnie Springs over Memorial Day weekend last year.

As an adult, I didn’t think much about Florida’s springs until I learned that their condition was in rapid decline due to overpumping and pollution. After seeing this damage firsthand, I lent my voice to help create more awareness of the threat to these cerulean natural wonders.

Since then, I have witnessed an explosion in popularity of our springs — in media of all forms, in public consciousness and, most importantly, in recreational use by the public. Now I wonder if the awareness we worked so hard to create is adding to the problem. Are we loving our springs to death?

Florida’s springs have always attracted humans. There is archeological evidence that people visited Warm Mineral Springs in North Port 11,000 years ago. At Silver Glen Springs in the Ocala National Forest, pre-Columbian people left an archaeological record of an 8,000-year history of “landscape alteration and construction,” according to archaeologist Jason O’Donoughue.

Spanish settlers built a mission near Fig Spring along the Ichetucknee River in the 17th century in their attempt to control the region’s indigenous population. After the Civil War, springs became a draw for out-of-state visitors, both for sightseeing and bathing in the waters of spring-based spas.

Boosters of White Springs claimed that their sulphur spring was the state’s first attraction, going back to the 1830s. The popularity of Silver Springs was unrivaled during the Gilded Age, when steamboats transported sightseers from Palatka up the winding Ocklawaha River to see the massive spring system there.

In the age of the automobile, no Florida roadside attraction was more popular than Silver Springs. Owners Walter Ray and “Shorty” Davidson used creative marketing tactics to lure motorists.

The pair enlisted Ocala’s Bruce Mozert to create fantastic underwater photographs that ran in newspapers nationwide, beckoning even more visitors. After driving patterns shifted to interstates and corporate theme parks overshadowed natural attractions, many of our springs became recreational destinations at county and state parks.

Today these wonders are beloved by many. The cyan waters are instantly recognizable on the Instagram feeds of a new generation of spring lovers. The lure of springs tempts many beyond springs country. I sometimes worry that we have promoted our springs too much.

A great example is the Ichetucknee, long a beloved destination for Gainesville residents even before it was a state park. When foot traffic from people wading in the river damaged fragile ecosystems, wading was banned from the northern part of the river and daily capacity was limited to 3,000 people per day. But online reviews of the privately owned Ginnie Springs still warn of excess crowds — one called it a “dumpster fire in a train wreck crashing into a Wal-Mart on Black Friday.”

In response, efforts have arisen to educate the public on proper springs etiquette. “Speak Up for Our Springs” signs started popping up at the springs at state parks urging people to avoid stepping on submerged underwater growth. The Howard T. Odum Florida Springs Institute created a video reminding people to “remember to keep your feet up, legs up and fins up” when swimming at a spring. These are good efforts and may make a difference.

Silver Springs is now a state park. Most of the vestiges of its roadside attraction days have been removed, with the notable exception of the beloved glass-bottom boats. But plans have been completed for construction of a swimming area — with a white sand beach and floating dock — similar to what was present during the park’s glory days. I have no doubt that swimming will again be popular at what was once perhaps the most visited spring in the world.

History shows that for thousands of years it has been impossible to resist the power of our springs. My hope is that we can become better stewards of these sensitive ecosystems so that future generations can experience their magic like I did as a kid.

Orlando-based writer and graphic designer Rick Kilby (rickkilby.com) is the author of “Florida’s Healing Waters: Gilded Age Mineral Springs, Seaside Resorts, and Health Spas” (University Press of Florida, 2020). The book received the silver medal for Florida nonfiction from the Florida Book Awards and the Florida Historical Society’s Stetson Kennedy Award. His first book, “Finding the Fountain of Youth: Ponce de León and Florida's Magical Waters” (University Press of Florida, 2013), won a Florida Book Award in the Visual Arts category.

This column is part of The Sun's Messages from the Springs Heartland series. More pieces from the series can be found at bit.ly/springsheartland.

Join the conversation

Share your opinions by sending a letter to the editor (up to 200 words) to letters@gainesville.com. Letters must include the writer's full name and city of residence. Additional guidelines for submitting letters and longer guest columns can be found at bit.ly/sunopinionguidelines.

Journalism matters. Your support matters.

Get a digital subscription to the Gainesville Sun. Includes must-see content on Gainesville.com and Gatorsports.com, breaking news and updates on all your devices, and access to the eEdition. Visit www.gainesville.com/subscribenow to sign up.

This article originally appeared on The Gainesville Sun: Rick Kilby: Are we loving Florida's springs to death?