Lowcountry Blacks have resisted oppression since the first enslaved Africans arrived

This is an opinion column by arts and culture columnist Maxine L. Bryant.

Master Storyteller Lillian Grant Baptiste often includes a powerful rhyme in her motivational talks. Part of it says, “minute by minute, hour by hour – if truth is light, knowledge is power.” I would add to that the words of George Bernard Shaw, “Beware of false knowledge; it is more dangerous than ignorance.”

Accurate knowledge matters and can change one’s thought trajectory. This was made apparent to me in a recent conversation I had with a friend who expressed aggravation that ancestral Africans didn’t put up a fight to resist being taken captive and brought to the what is now known as North America.

I could not believe my ears. Of course, I had to pause to educate them – because that’s what I do. My goal then was to provide a general discourse about ways Black people have resisted oppression. Here, I’ll focus on the resistance of Africans who were brought to the southeast shores of the colonies and formed Gullah Geechee communities in what would become the United States of America.

More from Maxine Bryant: Last month's Weeping Time commemoration another reminder to not forget the past

Resistance to enslavement

Captured Africans who were brought to the lowcountry did more than engage in passive resistance; their efforts helped to reshape the enslavement story. Acts of resistance by Gullah Geechee people along the Gullah Geechee corridor from the coasts of North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and North Florida follow a timeline that begins as early as 1527 and continues even now. Several such revolts happened near Savannah.

Let’s start in 1525 when a fleet of Spanish ships led by Lucas Vazquez de Ayllon sailed to North America carrying 600 to 700 people, supplies and livestock. About 100 of those people were enslaved Africans. The fleet’s flagship struck a sandbar and sank off the coast of South Carolina on Aug. 9, 1526. Ayllon and his men built a replacement ship and sailed 200 miles south to start a settlement.

Soon afterwards, Ayllon and many with him died of illness. A debate started among the survivors regarding next steps, and a new leader emerged. The enslaved Africans set fire to the new leader’s home and freed other captives and escaped to live with the local Native Americans. This incident is regarded as the first rebellion by captive Africans in mainland North America – long before the year 1619 with the arrival of 20 captured Africans in Jamestown, Virginia.

More from Maxine Bryant: Savannah is filled with Black women of history: Here are six local 'she-ros' to know

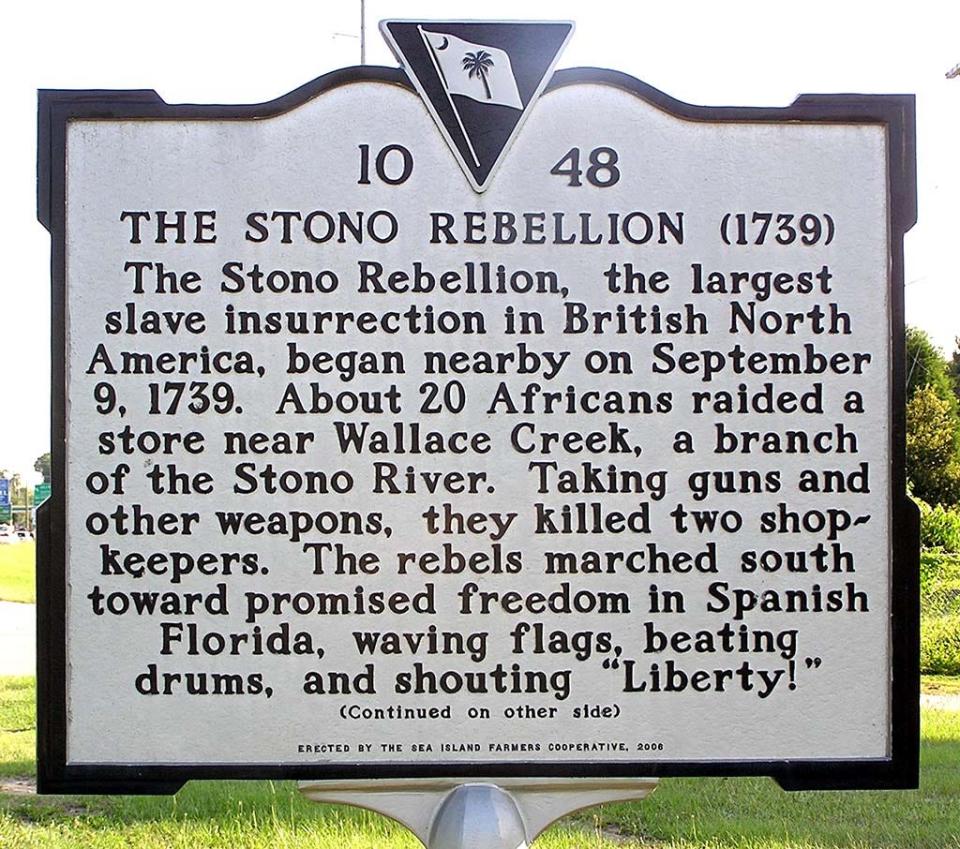

More than 100 years later in 1739, a group of about 20 enslaved Africans left a British colony in South Carolina and headed south towards Georgia and Florida. Known as the Stono Rebellion, their act of resistance to slavery resulted in the death of more than 60 people.

They were strategic about their rebellious act. They knew that the South Carolina Security Act required all white men to carry firearms to church on Sundays, thus they had a greater chance of successfully leaving the plantation without being shot. They broke into a store, armed themselves with guns, and marched southward calling for their liberty. They were apprehended at the Edisto River – but they fought a good fight.

Almost 40 years later, in 1775 white settlers in the New World went to war with Britain to obtain their freedom from the burdens levied on them by the British government. Interestingly, the very same people who fought for their freedom saw nothing wrong with enslaving Africans. A tactic used by the British to bolster their armies was to offer freedom to enslaved Africans if they aligned with them. About 20,000 Africans took them up on their offer and became known as Black Loyalists.

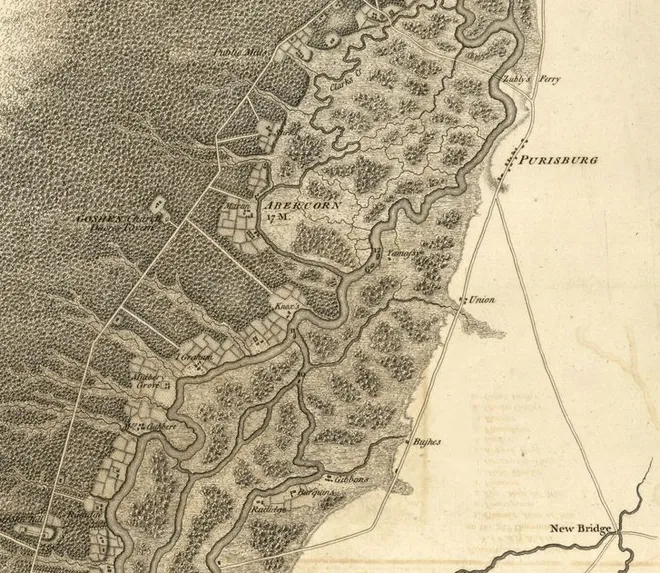

When the American Revolutionary War ended in 1783, a group of an estimated 100 previously enslaved Africans who had escaped and joined British forces decided to set up a maroon about 20 miles up the Savannah River. Maroons were hidden communities set up by escaped enslaved people that were designed to keep members hidden deep within forests or swamps, totally isolating themselves from the outside world.

The community outside of Savannah became known as Bear Creek and was believed to be one of the largest maroons in the U.S. and the only fortified camp. The population at Bear Creek resisted slavery by declaring themselves free and creating a hidden community to avoid being captured.

More: The story of the maroons is another gap in Savannah's history. Let's find ways to tell it.

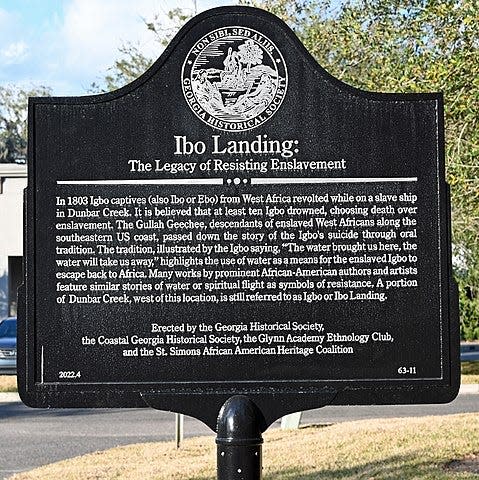

A factual story that has made it into the history curriculum of Coastal Georgia schools focuses on the Igbo Landing, a historic site on St. Simons Island in Glynn County. Rather than be enslaved, the Igbo people engaged in an act of mass suicide in 1803 by walking into the waters and drowning. This is a major act of resistance by Africans and has been referred to as the first “freedom march” in the history of the U.S.

Resistance to second-class citizenry

As early as 1941, there was a movement in Savannah to register every eligible Black person to vote in resistance to the existing power structure that kept the ballot out of their hands. However, state legislator Gene Talmadge had Black citizens purged off the books in Savannah which resulted in a significant lost of political power.

Strategic, united efforts by Blacks in Savannah resulted in movements such as the Savannah Protest Movement, the Chatham County Crusade for Voters, and other Black activists’ organizations. Refusing to be held back or down, Blacks in Savannah resisted white supremacists’ authority through sit-ins, Tybee wade-in by teens and strategically planned boycotts to protest voter oppression, segregation in stores and at lunch counters, unequal education, etc.

Their actions resulted in significant improvements – however, the fight against unjust systemic oppression continues even now. The struggle is real.

Resistance to economic exploitation

A contemporary fight on the barrier islands and within city boundaries involves residents who are resisting selling their homes to developers. Local residents in Pin Point, Carver Village, Cloverdale, Cann Park, Jackson Park, Cuyler-Brownville, Benjamin Van Clark, and more are engaged in a struggle to keep their communities safe from investors who recognize the value of their property.

Is African American resistance real in general? Yes. Is African American resistance real in Coastal Georgia and surrounding areas? Always has been. Always will be.

Maxine L. Bryant, Ph.D., is a contributing lifestyles columnist. She is an assistant professor, Department of Criminal Justice & Criminology; director, Center for Africana Studies, and director, Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Center at Georgia Southern University, Armstrong Campus. Contact her at 912-344-3602 or email dr.maxinebryant@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Savannah Morning News: Enslaved Africans regularly fought for freedom in colonies, US