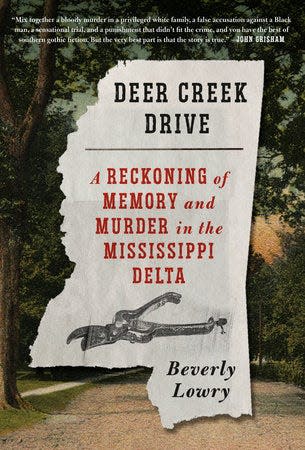

Lowery uses brutal slaying to illustrate how the deep south is a world apart in 'Deer Creek Drive'

She did it.

Murdered her mother. Savagely. With garden shears. In the middle of the afternoon.

At least that’s what people said, and what the jury concluded. She was convicted and sentenced to prison at the infamous Parchman Farm.

“Deer Creek Drive” recounts the brutal murder of Idella Thompson in the sleepy hamlet of Leland, Mississippi in 1948. Stabbed more than 150 times with those shears, Thompson’s body was discovered by her daughter Ruth, though inexplicably the shears had been washed of blood, though the rest of the gory scene resembled the set of a horror film.

When Ruth was charged with matricide, the story grew mythic and myriad, with neighbors lining up for and against the “socialite daughter” who lived on the same quiet street as her mother, a street, “which it is important to note — was and still is the most desirable in town.”

Author Beverly Lowery, a native of the same Mississippi Delta region, returned to nearby Greenville in 2018 where she was reminded of the long ago tragedy, and picked up the story both to reanimate history, and to revisit the turmoil of her own Delta upbringing, marked by a father who could never seem to find his footing, but who was always about to land on the next big thing. But more about that later.

First the murder and its aftermath.

Botched in a host of ways by investigators, including Leland police chief Frank Aldridge and officer Phillip P. ‘Pink’ Gorman, who found, 'Clearly, (Thompson had) been severely assaulted, her head and hands ‘all cut up,’ her clothes and body ‘bloody all over.’” Near the body, “A pair of metal pruning shears lay on the bathroom floor next to her head.” Otherwise the scene was oddly tidy.

And the murder scene lay open to others even while the investigation continued, the front door wide open and both neighbors and other investigators coming and going without regard to first finding clues.

Ruth, 42 and married to prominent landowner and planter John Dickins, was described by a family member as “‘plain as an old shoe.’” Claiming she’d encountered “a negro’” running from the scene, police followed Ruth’s assessment and put out alerts. No one, however, was identified as the culprit, and soon suspicion fell on the daughter, the motive being financial troubles and family strife.

Lowery uses the story to periodically explain her family’s connection to the Delta, where her father, someone she only later realized was a flim flam man, kept the family always one step ahead of his creditors, while as a teen she had to chart her way through changes–social and cultural–including her desire to come out as a debutante, as well as the decision by Earl Warren’s Supreme Court in Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, that sought to desegregate public schools.

The constant turmoil of her father’s suspect business practices in this tumultuous time marked Lowery’s childhood though she made it out, earning awards for her writing from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Guggenheim Foundation.

Back in the Delta, though, at a time stamped by social upheavals not seen since the Civil War, Ruth’s indictment and conviction remind us that while some have called the region “‘the most Southern place on Earth,’” and “‘cotton-obsessed and negro-obsessed,’” a place also once thought “the poorest, blackest region in the country,” race certainly mattered. Matters still.

Yes, Ruth Dickins was convicted of a heinous murder, and sentenced accordingly, but as Lowery makes clear in “Deer Creek Drive: A Reckoning of Memory and Murder in the Mississippi Delta,” status–and skin color–can go a long way toward determining how justice is delivered.

Good reading.

This article originally appeared on The Petoskey News-Review: Lowery uses brutal slaying to illustrate how the deep south is a world apart