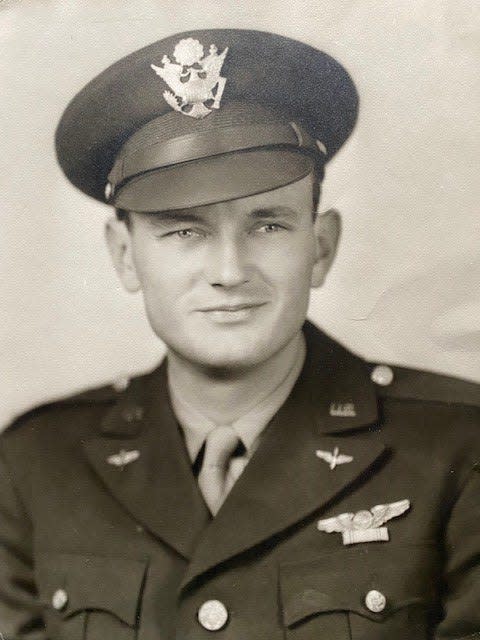

Lubbock's Jim Bill Clark, from the South Plains to hiding from the Nazis, Part 1

Jim Bill Clark documented his vivid recollections of his life growing up on the South Plains during the Great Depression, evading German capture during his time serving his country in World War II.

Larry Williams, the veterans liaison with the South Plains Honor Flight, recently reviewed Clark's documents to share his recollections from his early years as well as his adventures during World War II and beyond.

Portions Jim Clark's journals are being shared in a three-part series in the Avalanche-Journal. See part two in Sunday's edition.

Raised on the South Plains

The Lubbock native was born March 26, 1919, at West Texas Hospital in Lubbock to Sid and Key Clark during a sandstorm. His parents lived on a ranch west of Levelland. Shortly after his birth, they moved to Lubbock, and he spent his entire life on the South Plains except for five years and two stints in the military. He graduated from Lubbock High School in 1937 and enlisted in the Texas National Guard on July 21, 1937, where he was assigned to Battery C, 131st Field Artillery.

“The Depression was very much on in 1937," Jim recalled. "The reason I joined was because pay was $4 a month. We were sent to Camp Hulen near Palacios, on the Gulf Coast and were paid $1 a day for 17 days. I was in from 1937 to 1939 and in November 1940, we were mobilized into federal service, the same as being drafted into the regular Army. We went to Camp Bowie where I was eventually promoted to sergeant and was the chief of a seven-man crew operating a 75mm field artillery gun.

Joining the Army Air Corps

“One day in early 1942, there was an announcement on the bulletin board that any enlisted man that wished to take tests for pilot training in the Air Corps would be granted a three-day pass. The physical requirements remained the same, but the mental was reduced to an I.Q. test. My buddy, Tom Carle, and I applied for the pass, not thinking we could pass the tests. The tests were at Goodfellow Field in San Angelo. We scored high in the mental tests and perfect in the physicals. All we had to do was to take a 52-day leave with $105 per month pay while they got some schools ready to accept us. I went to Navigation school at Hondo and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant on December 17, 1942. I never did like it, but I think I was a real good celestial navigator."

Assigned to a Bomb Group

“I was transferred directly from Carlsbad to McDill Field, Florida to the 391st Bomb Group flying the Martin B-26 Bomber, known as the ‘Martin Marauder.’ It was an extremely fast twin-engine bomber. It had two 2,000 H.P. Pratt & Whitney engines and would cruise at 250 mph. It could even outrun a P-40. It was a new plane and full of bugs. I think they lost more planes at McDill Field than we did in combat. The slogan at McDill was, ‘One a day in the Tampa Bay.’ And it really happened that way! I was trained to navigate by the stars, sun, moon, and planets, all designed for long, over water flights.

Heading for Europe

“Our group commander, Col. Gerald Williams, was my kind of man. He would make John Wayne look like a sissy. I certainly had the greatest respect for him. He was a West Point graduate with 13 years of flying experience. It was the very middle of winter–January 1944. The weather was terrible over the northern route by way of Iceland. We couldn’t fly over 13,000 feet–not enough to fly over the North Atlantic storms, so we went the Caribbean route. We (finally) arrived in Land’s End, England with no fuel showing on the gauges.

Getting into the action

“I was in the service for three years before they sent me overseas. I was scared the war would be over before I got there. The German anti-aircraft fire was really accurate. We could be sure that we would be hit crossing the French coast on the way back and some in between. It was common to get two or three hundred holes in one plane on one mission. It sure kept the ground crew busy patching them. The crew members had a lot of armor plate around their positions, and we wore flak shirts which weighed about 37 pounds. The B-26 was a tough plane and could take a lot of punishment. It still could fly well on one engine. There were seven flyers that lived in the hut with me and after about seven months, there were only three of the original seven left.

D-Day in Europe

“On June 5, 1944, the crews were chosen for the D-Day mission. I was one of them. It was really top secret. They had armed guards at the doors of the briefing room, and we were sworn to secrecy. We were told to get some sleep and be back at 1:00 a.m. for another briefing. Our job was to take off about 3 or 4 a.m. and hit the coast of Normandy before the troops got there. Our target was (German) coastal artillery. We took off on instruments that day because the fog was so thick we could barely see the runway. We made it with no problems and were near the invasion site when the sun came up. It was really something to see. We were at about 10 or 12,000 feet, and there were ships as far as you could see in every direction. I couldn’t believe we had that many. All the B-17s, B-24s, P51s, P47s, P38s–everything we had that would fly was in the air. The coastal artillery was already firing at the invasion fleet. Every time they shot; it looked like a ball of fire. We knocked them out.

The Last Mission

“On July 8, 1944, 32 days after D-Day, our ground forces only had a small beachhead. On that day, I was assigned to the lead ship on a mission over France. On this mission we were to bomb a railroad bridge over the Loire River to slow down German reinforcements. We were told that the flak positions on the river were unoccupied, so we were to take a nice, long ten- minute bomb run down the river to the bridge. Those flak positions were occupied!..."

Cark's story will continue in Sunday's Avalanche-Journal.

Special thanks to Jim’s daughter, Susan Kincaid, and grandson, Kris Kincaid, for lending the author access to Jim’s documents and photos for this article.

This article originally appeared on Lubbock Avalanche-Journal: Lubbock's Jim Bill Clark, from the South Plains to hiding from the Nazis, Part 1