Lyme disease is ‘almost epidemic’ in parts of NC. What you — and your doctor — need to know

Lyme disease is a major threat in some western North Carolina counties and is moving east faster than most doctors’ awareness of it, a UNC epidemiologist says.

Carried by the black-legged tick, or deer tick, Lyme disease was once thought to occur only in the Northeast and Upper Midwest. And though it was documented in North Carolina at least as early as 1984, healthcare professionals in the state rarely think of it as a possibility when patients seek treatment with symptoms common to the illness.

In a paper published Wednesday by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Dr. Ross M. Boyce, an assistant professor of medicine and epidemiology at UNC’s Division of Infectious Diseases, urged doctors to be on the lookout for Lyme so patients can get treated early and have the best chance to fully recover.

Physicians also need to know testing for Lyme disease has improved, Boyce says, and that patients who have symptoms of the illness that can’t be otherwise explained but testing hasn’t yet confirmed as Lyme disease might benefit from prophylactic antibiotic treatment.

“When I went to medical school 10 or 15 years ago, we just didn’t see that much Lyme and we still don’t see a ton in this area,” Boyce told The News & Observer in an interview from Chapel Hill. “But it has really taken off in the western part of the state. It’s almost epidemic there; it’s taken off that fast in the past five or six years.

“And it’s much more common than it used to be in the central part of the state.”

What is Lyme disease?

The CDC says Lyme is the most common vector-borne disease in the U.S., caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi or, less commonly, Borrelia mayonii. Humans get it through the bite of infected ticks.

Symptoms usually start with fever, headache and fatigue. Most people will develop a skin rash around the site of the tick bite, but that can take a few days or up a to a month to appear. The rash is different from the bump or redness that can show up immediately after a tick bite.

If untreated, the CDC says, infection can spread to the joints, the heart and the nervous system, with the potential to cause long-lasting problems such as arthritis and even facial paralysis.

Who’s at risk for Lyme disease?

Boyce says Lyme disease requires three elements: the tick, the bacteria and the human.

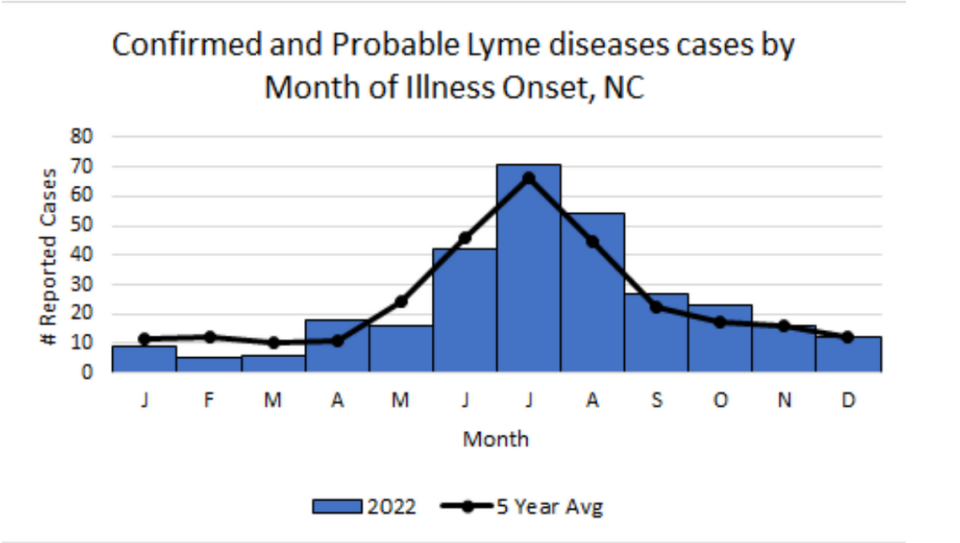

The three are most likely to come together when people spend time outside where infected ticks are active, which in the South usually starts in March or April.

And while hunting, hiking and camping may increase the risk of exposure by bringing people closer to the ticks’ habitat, anyone who goes outside — or has an indoor pet that goes outside — can come in contact with an infected tick.

The paper Boyce and seven of his colleagues published this week is a case study on a Raleigh woman who fell ill after a bike ride around her suburban neighborhood in July. She felt dehydrated and lightheaded and overtired for the amount of riding she had done. Four days later, had a fever of 101.4 and noticed a rash on her neck. A test for COVID-19 came back negative.

Over the next couple of months, other symptoms appeared and she consulted with different doctors, including at a local emergency room, was referred to a cardiologist and was tested for various issues and given different antibiotics. She developed back and neck pain and facial palsy, became forgetful and lost weight.

Finally, her children brought her to see Boyce, who ordered blood tests for several infectious diseases including Lyme, which came back positive.

“Other than the bike rides, her only risk factor for tick or mosquito exposure was working in the flower garden in her yard,” Boyce wrote. “She did note that there were frequently deer on the property and that the family dog often slept in her bed. She had not traveled outside the local area during the previous year.”

Boyce prescribed a course of doxycycline, the antibiotic most commonly used to treat Lyme disease. The woman was significantly better in three days and a month later, was recovered.

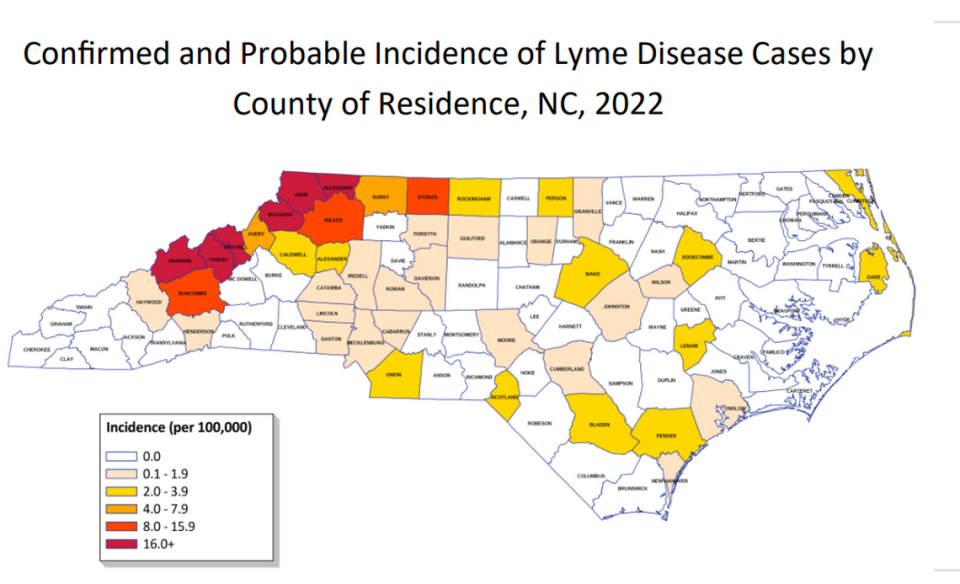

Where is Lyme most prevalent in North Carolina?

While not all infections get reported, statistics kept by the CDC show that:

▪ Six N.C. counties were among those with the highest rate of Lyme infection in 2022, with 16 or cases more per 100,000 population. All in the northwest corner of the state, they are Alleghany, Ashe, Watauga, Yancey, Mitchell and Madison counties.

▪ Buncombe, Wilkes and Stokes counties each reported from 8 to 15.9 cases per 100,000 residents.

▪ Avery and Surry counties reported 4 to 7.9 cases per 100,000 people in 2022.

▪ Wake is among 13 counties reporting from 2 to 3.9 cases per 100,000 people.

▪ Twenty counties in the state, including Orange and Johnston, reported 0.1 to 1.9 cases per 100,000.

▪ About half the counties in the state, including Durham, reported no cases of Lyme in 2022.

What if I find a tick on me?

The CDC says it usually takes from 36 to 48 hours or more for the Lyme disease bacterium to be transmitted. If you remove a tick quickly — within 24 hours — it greatly reduces the chance of getting Lyme disease.

To remove a tick:

▪ Use clean, fine-tipped tweezer to grab the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible.

▪ Pull the tick up with steady, even pressure, without twisting or jerking.

▪ Clean the bite area and your hands with rubbing alcohol or wash with soap and water.

▪ Dispose of the tick by putting it in alcohol, sealing it in a bag or container, wrapping it tightly in tape or flusing it down the toilet.

Can I get Lyme from eating deer meat?

No.

Can dogs spread Lyme?

The CDC says that dogs and cats can get Lyme, but there is no evidence they spread it directly to their owners. However, they can bring infected ticks into the yard, and a human bitten by an infected tick can develop Lyme.

Can I get Lyme from someone else?

Lyme is not spread from person to person, and the CDC says there is no evidence it’s spread through air, food, water, or from the bites of mosquitoes, flies, fleas, or lice.

How is Lyme disease treated?

Oral antibiotics such as doxycycline or amoxicillin can effectively treat Lyme disease, and the earlier they’re administered, doctors say, the less likely patients are to develop lasting problems.

In fact, Boyce said, patients who have symptoms consistent with Lyme that can’t be explained by another diagnosis, but whose blood work hasn’t come back yet showing positive for Lyme, might benefit from a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline.

Testing for Lyme has improved, Boyce said. In 2019, the CDC approved a testing method that’s easier to interpret than previous methods and is more sensitive, meaning it can detect the disease earlier. Some commercial laboratories in North Carolina have already moved to the modified test, he said.

Ticks pose a serious danger in North Carolina. What to know.

7 critters you may cross while hiking in NC this summer, and what to know about them

Chiggers infected with potentially deadly bacteria found in NC. Here’s what to do.