Lynsey Addario Wants Her Photographs to Show Politicians the Raw Truth of War

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In one photograph stand two women in bright blue burqas billowing in the wind on the side of a mountain in Afghanistan, awaiting transport to a hospital, where one of the women will soon give birth. Their car broke down en route to the hospital, and soon they’ll catch a ride with Lynsey Addario, the Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist who took this picture of them in 2009, with sweeping blue skies and wispy clouds stretching seemingly endlessly behind them.

This photo and others—of volunteer fighters lined up outside a base in Benghazi before clashing with troops aligned with dictator Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, or of Eyerus, a 40-year-old woman swathed in a sheer, cream-colored scarf covering half of her face as she recovers from being captured and raped by Eritrean soldiers in 2021—can be viewed at an exhibit of Addario’s work at the SVA Chelsea Gallery in New York.

This Is How the U.S. Totally Misjudged the War in Ukraine

The exhibit, which spans her more-than-two-decade career and includes photographs, notes, video, and audio, and even a weighted flak jacket Addario has used for protection on the front lines, is not for the faint of heart. Addario, 49, has worked in over 80 countries, on five continents, and her photos of atrocities, wounded soldiers, maternal mortality, the climate crisis, and more, can at times be alarming.

For Addario, that’s the whole point.

“I’m shooting for proof, for documentation. I’m shooting to create awareness for the rest of the world. I’m shooting so policymakers can see those images and bear witness to them through my lens,” said Addario, who spoke briefly over the phone with The Daily Beast twice in November, including once from Ukraine, where she was on assignment covering Russia’s war. “I’m shooting to give a voice to people who have something to say.”

Noor Nisa, 18 (right), in labor and stranded with her mother in Badakhshan Province, Afghanistan, November 2009.

It’s definitely a hard-hitting collection of images, but the exhibit is also moving and beautiful. Addario’s images of women in Afghanistan or of those who have survived conflict-related sexual violence may be difficult for visitors to view, but they are also some of the most striking.

“I try to make images that are compelling and that are sometimes beautiful, if they have beautiful light even if the subject matter is difficult. Because my goal is to draw people in,” Addario told The Daily Beast. “My goal is to get people to pay attention to the subjects I’m covering.”

The exhibit, which is Addario’s first mid-career solo retrospective and curated by Maya Benton and Perri Hoffman, takes visitors chronologically through her career, displaying photographs from her first pitch on women in Pakistan to The New York Times Magazine just days after the 9/11 attacks, to Iraq and Libya (where she was kidnapped), to famine in Yemen, to genocide in Darfur, and to fires in California. The exhibit displays photographs of her current work in Ukraine, too.

The exhibit sports several display cases of items that show Addario's innermost thoughts and grit while on assignment, from a display case showing the jacket she was given when she was taken hostage in Libya in 2011, to letters and notes she wrote in the field.

“I question daily why I send myself on these impossible shooting missions,” Addario wrote from Islamabad in one undated letter on display. “This is the first time I feel actual fear in my stomach. Entering a region where women are valued at the rate of two cows, where they are raped repeatedly by the Taliban, and then jailed or stoned to death for becoming pregnant with their illegitimate children.”

Eyerus, 40, poses for a portrait in a safe space for victims of sexual assault in the Ayder Hospital in Mekele, Tigray, Ethiopia, May 2021.

Some of the exhibit touches on her early days as a photojournalist, when she snapped photographs of Madonna at the Casa Rosada, where she was filming Evita, for the Buenos Aires Herald. Addario later traveled to Afghanistan, well before the attack on the Twin Towers, to cover women living under the Taliban, which left her uniquely positioned to later embed with U.S. troops there.

Addario, who is best-known for her work in the Middle East, South and Central Asia, and Africa, was born and raised in the United States and began taking photographs when her father gave her her first camera—a Nikon FG—when she was about 13. She taught herself the basics from a manual on how to take photographs in black-and-white, later moving on to street photography while studying in Bologna and then interning for a fashion photographer in New York City. She later photographed for the Buenos Aires Herald and worked her way onto the Associated Press’ stringers list.

From there she went on to shoot for The Boston Globe, The New York Times and several other outlets from India, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Iraq, later spidering out to Sudan, Congo, Libya, and dozens more countries to bring visceral visual news from conflict and disaster around the world.

While the exhibit is a retrospective, it also demonstrates Addario's interest in ensuring her work has an ongoing impact. Her work from Ukraine this year, where she is working to document the cascading effects of Russia’s war on civilians, has exposed the harsh realities of war for the world to see and helped world leaders chart a path forward on how to handle the senseless attacks Russian President Vladimir Putin is unleashing on Ukrainians.

Ukrainians clean up debris after a residential building was hit by Russian missiles in south Kyiv, Ukraine, February 2022.

In the early days of Russia’s war in Ukraine this year when Russian forces were advancing towards Ukraine’s capital and Ukrainians were evacuating nearby cities, a Russian mortar hit and killed a family fleeing in Irpin, west of Kyiv. Addario and her team were just yards away and witnessed the entire attack, which killed the fleeing mother, her two children, and a family friend.

The photographs she took that day of the aftermath have served as direct evidence of either Russia’s targeting of civilians, or disregard for civilian casualties, and have been pivotal in building a global understanding of Russia’s ruthless invasion of Ukraine.

In recent days, Addario’s journalism from Ukraine—and going places she isn’t necessarily supposed to—has been pivotal in sharing those stories. Addario spoke with The Daily Beast over the phone from Kherson, from which Russian forces fled earlier this month, leaving behind their last stronghold west of the Dnieper River in a major victory for Ukraine.

“It has been pretty incredible to watch the city change back to Ukrainian hands. People have been completely overwhelmed with emotion, relieved,” Addario said, adding that although the government of Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky had barred journalists from entering the city, she didn’t think she could pass this moment up to document the liberation and not go. “Of course many of us did because it was incredibly newsworthy, and it was an incredible moment and not one that we could sort of wait on.”

Other photographs Addario has taken through the years have also inspired change. Photographs she took covering maternal mortality in Sierra Leone, where Mamma Sessay, 18, died shortly after delivering twins, exposed for the world to see just what exactly it meant for Sierra Leone to have one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world. After Addario’s photographs of Mamma Sessay’s journey through childbirth and post-partum hemorrhaging circulated at Merck, Merck announced “Merck for Mothers” and dedicated $500 million for maternal mortality programs.

At times, though, some editors have kept Addario’s images from public view, out of a fear that they may be too graphic. The exhibit displays a series of Addario’s photographs of wounded American soldiers in Fallujah, Iraq in 2004, which she took on assignment for Life magazine. The series includes a foreboding red and grey photograph of over a dozen American soldiers lying down on stretchers and others being carried to treatment.

US troops carry the body of Staff Sergeant Larry Rougle, who was killed when Taliban insurgents ambushed their squad in the Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, October 2007.

Addario had five days at Balad Air Base to photograph injured American soldiers leaving en route to Ramstein Air Base in Germany to receive further treatment. That kind of access, she shared, was unprecedented at the time for journalists, and she thought her photographs would reveal to Americans the true toll of the war for U.S. troops and could lead to war protests or some kind of resistance in America.

But after months of deliberation, Life declined to publish the images out of a concern that they were too graphic, Addario said.

“We had really good access, access that I hadn’t really seen other journalists have at that point in the war,” Addario told The Daily Beast, and understanding “the value of those images—wounded soldiers that hadn’t really been published,” she worked to get them published so that the world could see what was happening in Iraq more fully. Addario was able to get them published a few months later, when she took the photographs to the New York Times Magazine under the leadership of Kathy Ryan, now the director of photography at the magazine.

A spokesperson for Dotdash Meredith, which now owns the Life magazine brand (its parent company is IAC, which also owns The Daily Beast), declined to comment since the shoot predates Dotdash Meredith's ownership.

In Russia’s war in Ukraine, so far, Addario hasn’t encountered as much resistance.

“The image of the family that was killed in front of me on the Irpin bridge—I was surprised The New York Times ran that photograph. But I think their decision to run that photograph was fundamental in the sense that it came at a time in the war where I don’t think people realized that civilians were really deliberately being targeted,” Addario told The Daily Beast. “That image… changed the dialogue of the war.”

Journalists often talk about how they are publishing the first draft of history, and in a world where accusations of “fake news” fly around with abandon, Addario’s photographic documentation of atrocities and the realities of conflict around the globe form a cornerstone of setting the record right—and our understanding of conflicts may very well depend on it.

One hundred and nine African refugees from Gambia, Mali, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Guinea, and Nigeria are rescued by the Italian navy from a rubber boat in the sea between Italy and Libya, October 2014.

“There’s been a lot of rhetoric about fake news and I think it’s really important to understand that this is not political. This is a documentation of our times,” Addario said, adding that with the exhibit, “I wanted to give people an understanding of how journalists work and why it’s important and why photojournalism and why journalism is important for our society.”

Throughout the exhibit, visitors will note that Addario isn’t just some adrenaline junkie chasing the latest bloody battlefield moment. For her, it’s about telling the stories of civilians caught in the crosshairs of conflict, the fallout of the war, and the real people on the other side of her camera lens.

“I don’t really believe in sort of gratuitous violence in terms of just shooting dead people or people who have just been killed just for the sake of that… I tend to stick to places where I can cover civilians and the reactions of civilians and the toll of war on civilians,” Addario told The Daily Beast.

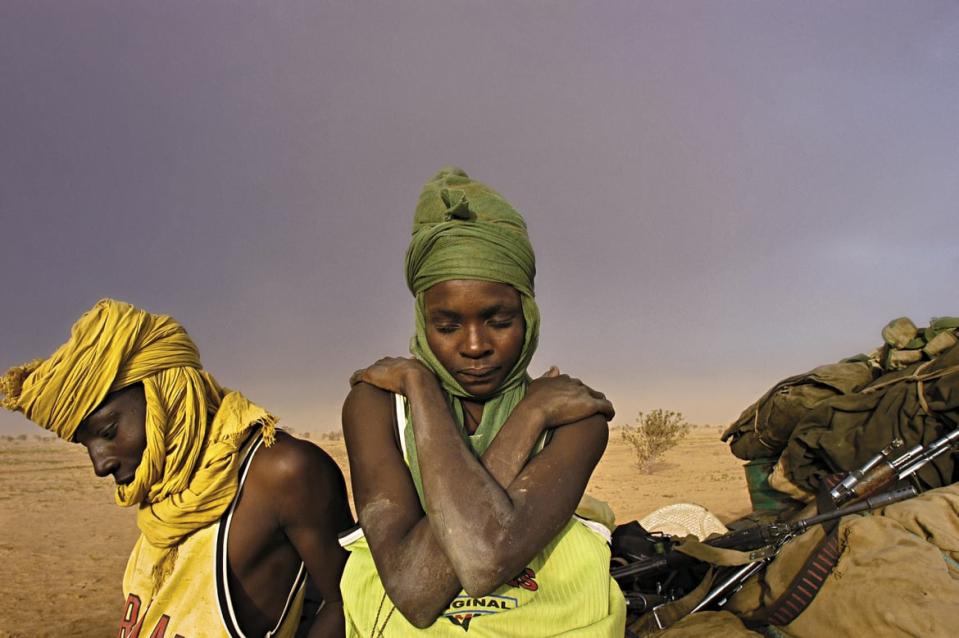

Soldiers with the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army sit by their truck, waiting for it to be repaired, as a sandstorm approaches in Darfur, Sudan, August 2004.

For Addario, it’s near impossible to detach from the issues she covers when she’s back home.

“It’s very hard… when I’m not covering a story like Ukraine that I’ve been covering all year, I’m sort of always thinking about the fact that I should be there and not home and that’s crazy because I have two children, you know? I have a family,” Addario said.

To try to unwind, Addario makes sure to spend a lot of time with friends and family at dinner parties and makes it a point to take care of her mental and physical health by exercising often as well, she said. But even when she’s home, she is thinking about what she’s covering.

“I don’t just disconnect at all. I’m constantly reading news and watching news and scanning headlines and thinking about the fact that I have one foot in whatever conflict I’m covering, and one foot at home,” Addario said.

The Masters Series: Lynsey Addario is at SVA Chelsea Gallery, 601 West 26th Street (15th floor), until Dec 10.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.