Lyrid fireballs may light up your night sky this weekend. Here's how to watch

Eyes to the sky Friday and Saturday night! The Lyrids, the first meteor shower of spring, is reaching its annual peak!

From the January Quadrantids to the December Ursids, roughly a dozen prominent meteor showers light up our night skies each year. Through much of the year, the longest waits between meteor shower peaks that astronomers, stargazers, and night-sky enthusiasts endure are the lulls in activity through June and September. However, early in the year, there's what could be described as a meteor shower drought. Once the Quadrantids peak in early January, there is a roughly three and a half month wait until the Lyrids in late April.

That 'drought' ends this weekend, though.

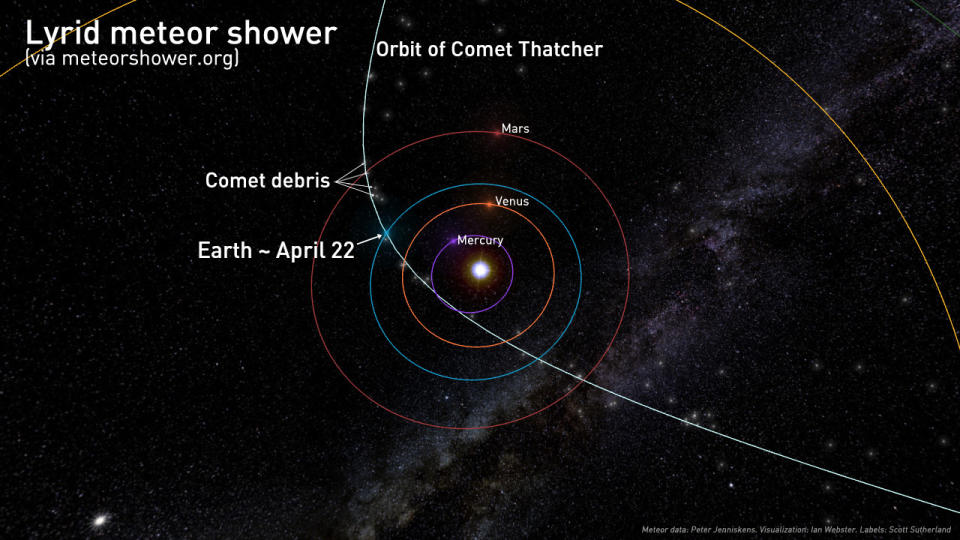

This simulation shows the orbit and debris stream from Comet Thatcher, as viewed from far 'above' the solar system's orbital plane. The locations of the inner planets are indicated as of April 22, 2023, with Earth very close to the orbital path of the comet. Credit: Meteorshowers.org/Scott Sutherland

Right now, as our planet travels through space, it is passing through a stream of dust, ice, and gravel left behind by a comet known as C/1861 G1 (Thatcher). Those bits of comet debris that are caught directly in the path of Earth are swept up and plunge into the upper atmosphere, producing brief, sometimes exceptionally bright flashes of light.

This is the Lyrid meteor shower, which is active each year between April 15 to April 29, and reaches its peak over Earth Day, on the nights of April 21-22 and April 22-23.

The apparent origin point of Lyrid meteors, known as the radiant, is shown here near the bright star, Vega, on the night of April 22. Credit: Stellarium/Scott Sutherland

Nearly all meteor showers follow a similar pattern. They begin with just a few meteors zipping by overhead in the first few nights. Although on any night of the year, you can probably look up and see at least one or two meteors, the difference here is that these all originate from the same relative point in the night sky, known as the 'radiant'. Night by night, as Earth gets deeper into the debris stream, the number of meteors increases until it reaches a peak. After that, the numbers ramp down again until the planet exits the stream.

Comet Thatcher's debris stream tends to be sparse compared to some of the more active meteor showers (such as the Perseids, Geminids or Quadrantids). Even at their peak around the night of April 22, the Lyrids typically deliver around 20 meteors per hour.

That's one meteor every five minutes or so, which isn't too bad of a show. This is especially true considering that the Lyrids are well-known for producing bright fireballs!

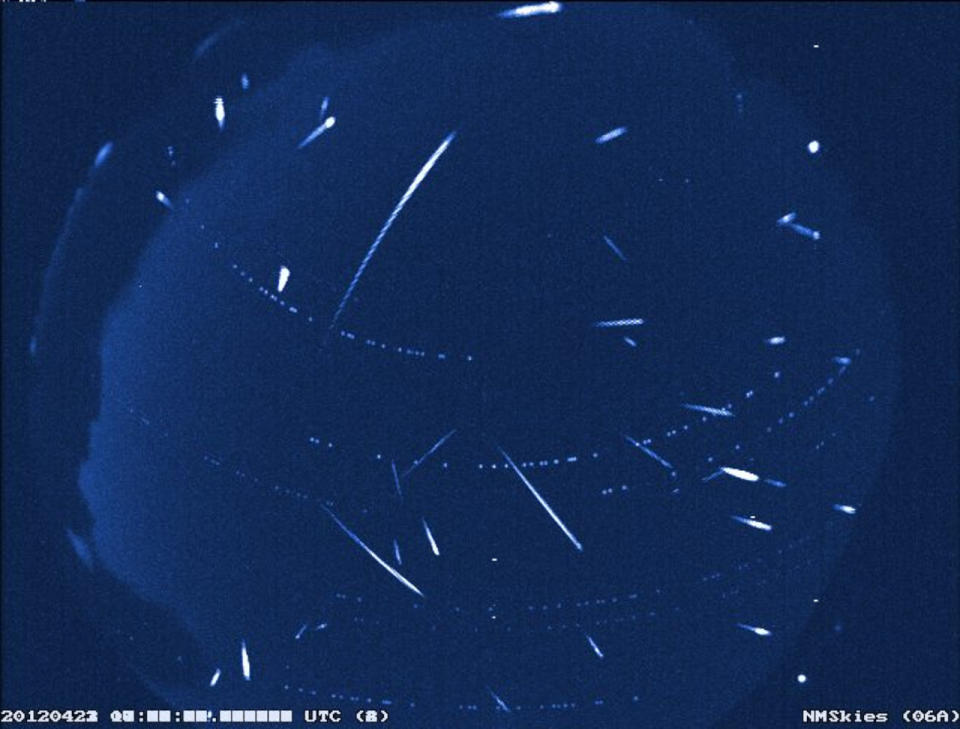

This composite all-sky camera image shows a mix of Lyrid and non-Lyrid meteors over New Mexico from April 2012, including a few Lyrid fireballs. NASA/MSFC/Danielle Moser.

Also, if you are out observing the Lyrids, consider that you're viewing the oldest of all the meteor showers we see each year. According to records, it's been observed for over 2,700 years!

Plus, while we only see 10-20 meteors per hour from the Lyrids, every 60 years, there's an 'outburst' of exceptional activity.

According to Sky and Telescope magazine, "Chinese court astronomers reported a Lyrid outburst on March 16, 687 BC when 'in the middle of the night, stars fell like rain.'

In 1982, during the last outburst, the Lyrids rivalled the August Perseids, as it produced over 100 meteors per hour during its peak. The next such outburst is expected in 2042.

WILL WE SEE IT?

The Lyrid radiant rises in the northeast sky roughly an hour after sunset. It then tracks higher into the sky throughout the night, reaching its highest point (near zenith) just before dawn. Thus, it's possible to see meteors from this shower all night long.

With only a thin Crescent Moon in the sky during this year's peak, which sets within a couple of hours of the Sun going down, this is an ideal year to view this meteor shower.

The absolute best time to watch tends to be in the hours between midnight and dawn. That's the darkest time of the night, and when the meteor shower radiant is highest in the sky.

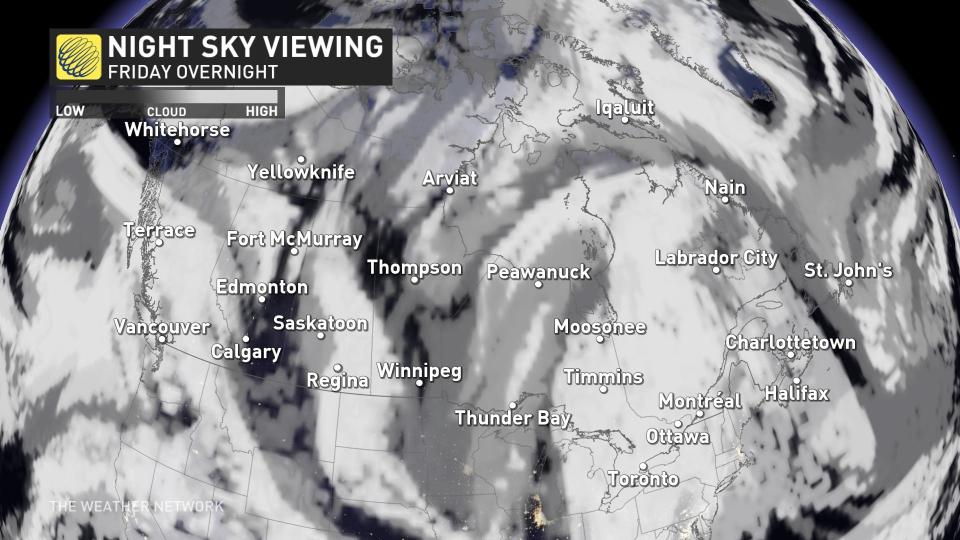

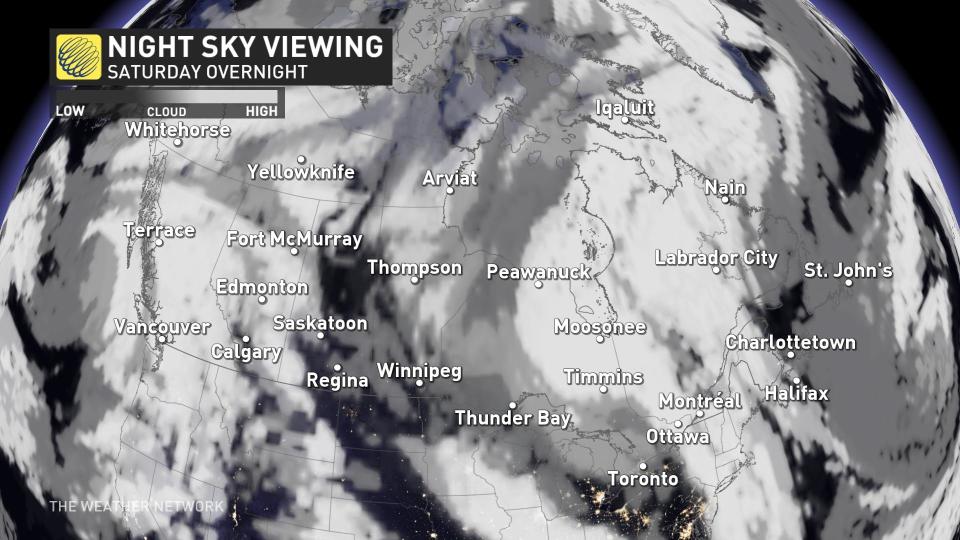

However, the weather is going to be a big factor this year, as there is plenty of cloud cover in the sky this weekend.

On Friday night, southern and central Alberta, and perhaps southern Manitoba appear the best locations from which to watch.

For Saturday night, the clear skies move from Alberta to Saskatchewan and Manitoba, and southern Ontario may see some breaks in the cloud cover throughout the night.

Be sure to check your local forecast, though, as even a few hours of reasonably clear skies will be enough to catch a glimpse of the meteor shower.

WATCH FROM ANYWHERE

If you're trapped under cloudy skies on Friday and Saturday night, there are still ways to experience this event.

The Virtual Telescope Project plans to host a live stream on the night of April 23, starting at 8:30 p.m. EDT, providing colour images from their new all-sky camera.

Also, we can listen to the meteors as well, via the Meteor Echoes Livestream. When meteoroids plunge into the upper atmosphere, they each produce a little shockwave that can be picked up by radar. Meteor Echoes converts this radar data into sound, presenting the blips in their livestream from meteors detected over the US Northeast and Nova Scotia.

METEOR? METEOROID? METEORITE?

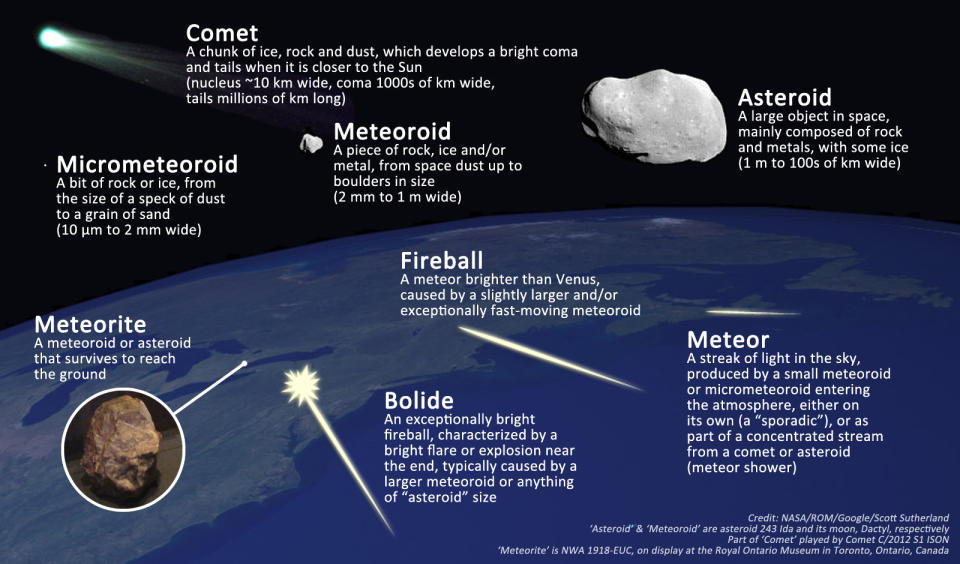

There are a lot of similar-sounding words that get tossed around during events like these, and it's easy to get them mixed up. So here's a short guide to help.

The bright streaks we see during the Lyrids are known as meteors.

Image via Unsplash: Austin Human @xohumanox

Each meteor occurs due to a meteoroid — a piece of rock or ice the size of a speck of dust up to a grain of sand — plunging into Earth's upper atmosphere.

Meteoroids travel at incredible speeds, typically measured in kilometres per second! When they hit the atmosphere, they compress the air in their path, turning that air into a white-hot glowing plasma. Sometimes they will shine with other colours, based on the composition of the atmosphere they're flying through, or due to specific minerals vapourizing off the meteoroid itself.

A typical meteor flash tends to last a second or less. Larger meteoroids, from a pebble to a boulder in size, produce much brighter and longer-lasting meteors, which we call fireballs. Some fireballs emit bright flashes along their path, which indicates that the meteoroid is exploding apart due to the intense pressure exerted on it by the atmosphere. These are often referred to as bolides.

Regardless of how big and bright a meteor is, it 'winks out' when one of two things happens. Smaller meteoroids tend to completely vapourize due to the heat of the plasma around them, and the meteor winks out once that happens. For larger meteoroids, the air in their path pushes back against them, slowing them down until they can no longer exert enough force to compress that air into a plasma.

Any parts of the meteoroid that survive past this point enter what's known as dark flight. Basically, they become rocks falling under the force of gravity. If we find these rocks on the ground, we call them meteorites.

Related: Want to find a meteorite? Expert Geoff Notkin tells us how!

TIPS FOR METEOR WATCHING

Meteor showers are events that nearly everyone can watch. No special equipment is required. In fact, binoculars and telescopes make it harder to see meteor showers, by restricting your field of view. However, there are a few things to keep in mind so you don't miss out on these amazing events.

The three best practices for observing the night sky are:

Check the weather,

Get away from light pollution, and

Be patient.

Check the weather

Clear skies are essential. Even a few hours of cloudy skies can ruin your chances of watching an event such as a meteor shower. So, be sure to check The Weather Network on TV, on our website, or from our app, and look for updates on our Space News page, just to be sure that you have the most up-to-date sky forecast.

Get away from light pollution

Next, you need to get away from city light pollution. Look up into the sky from home. What do you see? Some passing airliners? The Moon, a planet or two, perhaps a few bright stars such as Vega, Betelgeuse and Procyon? If so, the light pollution in your area may be too bright for watching a meteor shower.

Keeping streetlights and other light sources out of your direct line of sight will help. However, to get the most out of a meteor shower, it's best to watch from outside the city. The farther away you can get, the better.

Watch: What light pollution is doing to city views of the Milky Way

For most regions of Canada, getting out from under light pollution is simply a matter of driving outside of your community until many stars are visible above your head.

In some areas, especially in southern Ontario and along the St. Lawrence River, the concentration of light pollution is too high. Getting far enough outside of one city to escape its light pollution tends to put you under the light pollution dome of the next city over. The best options for getting away from light depend on your location. In southwestern Ontario and the Niagara Peninsula, the shores of Lake Erie can offer some excellent views. In the GTA and farther east, drive north and seek out the various Ontario provincial parks or Quebec provincial parks. Even if you're confined to the parking lot after hours, these are usually excellent locations from which to watch (and you don't run the risk of trespassing on someone's property).

If you can't get away, the suburbs can offer at least a slightly better view of the night sky. Here, the key is to limit the amount of direct light in your field of view. Dark backyards, sheltered from street lights by surrounding houses and trees, are your best haven. The video above provides an excellent example of viewing based on the concentration of light pollution in the sky. Also, check for dark sky preserves in your area.

When viewing a meteor shower, be mindful of the phase of the Moon. Meteor showers are typically at their best when viewed during the New Moon or Crescent Moon. However, a Gibbous or Full Moon can be bright enough to wash out all but the brightest meteors. Since we can't get away from the Moon, the best option is to time your outing right, so the Moon has already set or is low in the sky. Also, you can angle your field of view to keep the Moon out of your direct line of sight. This will reduce its impact on your night vision and allow you to spot more meteors.

Be patient

Once you've verified you have clear skies, and you've limited your exposure to light pollution, this is where being patient comes in.

For best viewing, your eyes need some time to adapt to the dark. Give yourself at least 20 minutes, but 30-45 minutes is best for your eyes to adjust from being exposed to bright light.

Note that this, likely more than anything else, is the one thing that causes the most disappointment when it comes to watching a meteor shower.

Stepping out into your backyard from a brightly lit home and looking up into the sky for five minutes, you might be lucky enough to catch one of the brighter meteors. It's far more likely, though, that you won't see anything at all. Meteors could be streaking by overhead, but we can't see them because our eyes haven't yet adjusted to the dark.

However, we can dramatically improve our chances of avoiding disappointment just by giving ourselves about twenty minutes to adjust, while avoiding light sources — streetlights, car headlights and interior lights, and smartphone screens — during that time.

If avoiding your smartphone isn't an option, set the display to reduce the amount of blue light it gives off and reduce the screen's brightness. That way, it will have less impact on your night vision.

You can certainly gaze up into the starry sky while letting your eyes adjust. You could spot a planet or two, see the brightest stars and constellations, and possibly even a few of the brighter meteors as your eyes become accustomed to the dark.

Once you're all set, just look straight up and enjoy the view!

(Thumbnail image courtesy Graham Fielding Photography, who uploaded this image into The Weather Network's UGC gallery)