I’m a Psychiatrist and It Took My Entire Life to Figure Out My ADHD Brain

In the fourth grade, on a day that we had a substitute teacher, I convinced the kids in my class to form a coup by standing on our desks and chanting loudly. I don’t remember why, but I suspect that it was boredom, a state of mind that often prompted me to seek out ways to entertain myself. On the inside, I knew that I was smart, creative, and rambunctious, but my teachers would call me “troublesome,” “disruptive,” and “consistently inconsistent.” That last one stuck with me forever. After my parents heard about my behavior from the school, they took me to the pediatrician. The doctor prescribed me Ritalin.

My ADHD journey began that day, but my parents made the choice not to tell me about my diagnosis because they were worried it would impact my self-esteem and self-worth. They disguised my Ritalin as a “vitamin" and the “vitamin” worked! Suddenly, 45-minute classes weren’t so torturous. I was able to take notes and stay organized. My desk was a functional workspace instead of a shadowy pit of crumpled papers and old Lunchables boxes. I could answer questions without the sounds of the clock ticking disrupting my thoughts.

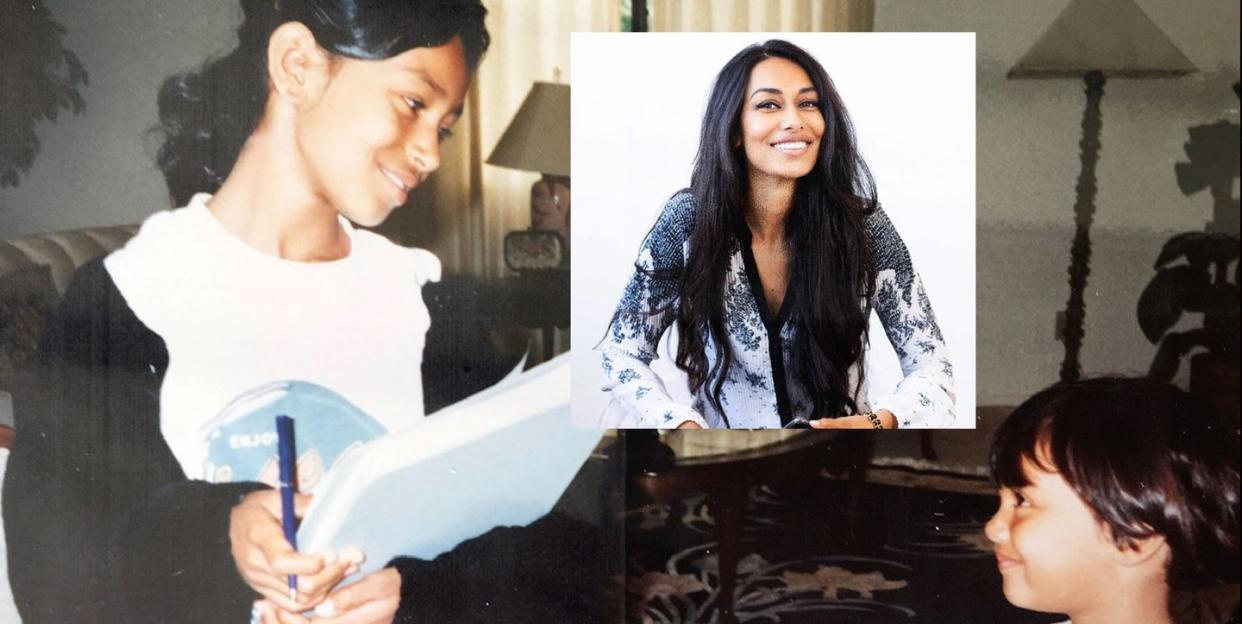

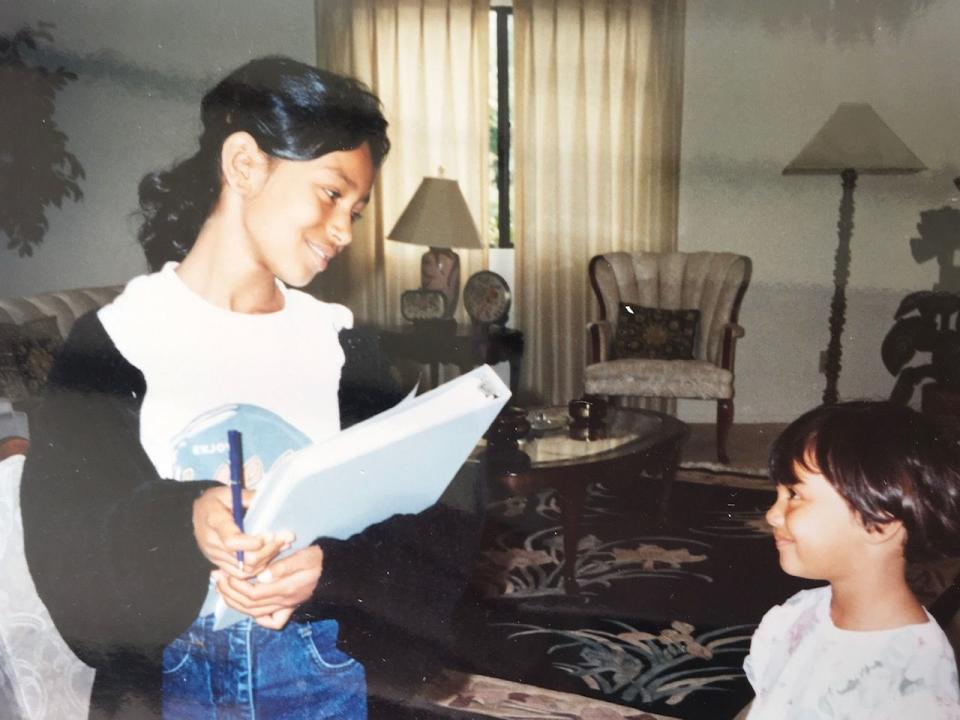

I started to truly enjoy learning and sailed through elementary school. I went to California’s state spelling bee three years in a row, completed a full year of coursework the summer before school started because I wanted to be “prepared,” and took practice SATs before starting high school. I knew that I wanted to go into medicine, so in the ninth grade, I researched ways to get into medical school right out of high school. I turned down numerous full-ride scholarships at Ivy League colleges to start at the University of Missouri Kansas City’s six-year Accelerated BA/MD program, so I could become a doctor sooner.

College was the first time I had to function independently. On my first anatomy test, I scored 62 percent, a grade so low that I couldn’t comprehend it. I reluctantly told my parents and they asked if I was taking my vitamin. I wasn’t. The “vitamin” part of my day slipped away in the process of learning how to live on my own. It was then that they revealed the truth about my ADHD diagnosis and Ritalin prescription.

Instead of accepting the truth, I rebelled. I felt betrayed, disheartened, and confused about my own achievements. I felt as if I had been “drugged” into performing. I refused to take my medication and studied harder than I had ever. On my next test, I got a 68 percent and fell apart. I used to be a great student who always aced tests and was accepted to Ivy League schools, but that image of myself shattered the minute I realized I couldn't be that person without medication.

So I stopped caring. If I couldn’t perform the way I had before, I would be the “fun” girl! I went out and made friends with people that didn't care about studying, using my new social circle to mask the grief of losing my old identity. But the party life didn’t sustain me.

I watched other students in my program sail past me academically and felt even worse about myself. I sporadically took my medication and, as a result, my sleep schedule was all over the place and I wasn't eating. Months later, I decided it was time to go home and talk to my parents. Their response: “Knowledge is power.” It was the same thing they told me when I was bored or restless as a kid. They wanted me to fill my time expanding my brain. This time, I finally listened to them. I traded studying for an upcoming test to study the history of ADHD, the symptoms, the diagnosis, the treatment, and the controversy. I went fully off my medication again and unveiled the distractibility, emotional dysregulation, and sense of overwhelming pressure to function. Now I could fully and confidently understand my symptoms as an actual mental health issue, not a character flaw.

The next few years were a roller coaster. Going back on medication after my experimental period helped me see multi-step processes, like how to plan my day and, eventually, how to plan the rest of my medical school career. It helped me ignore extraneous stimuli and see what was important. I could finally take a breath without feeling like my house was collapsing around me. However, it killed my appetite, disrupted my sleep, and intensified my mood, which didn’t happen when I took it as a child. The combination of aging, hormones, increased workload and stress, and lack of structure made this a completely different ballgame.

My standing in the University was constantly in question due to my inconsistent academic performance, but by some miracle (by miracle, I mean the endless help and support of my parents—especially my mom, who moved to Kansas City for a month to make sure I was eating and taking my medication), I was able to complete medical school. I started studying pediatrics, then switched my career focus to psychiatry. I even changed my relationship with medication, now pairing it with behavioral modifications like building organizational routines and reframing previous failures as learning opportunities. For example, I was able to see my “failure” of graduating six months later than I planned as valuable time spent learning how to use my unique brain to help others. I left school with a deeper understanding of those traumas and a more complete vision of myself, both as a physician and a person. I realized that I just needed the right environment and behavioral alterations to nourish my brain. I began to capitalize on my strengths (the creativity, the tenacity, and the enthusiasm for life) instead of bemoaning my shortcomings. It was such a welcome departure from the tired old rhetoric that I was lazy or lacked the discipline to do hard things.

Now, I’m a board-certified psychiatrist that specializes in ADHD, I wish little fourth-grade Sasha could grow up in a time when ADHD wasn’t stigmatized. And I wish the people closest to me didn’t have to endure the emotional turmoil of watching me flounder for years. Although, if that hadn't been our path, maybe ADHD wouldn’t have become my passion project? Being able to reach my patients and lean into advocacy through social media (I’m a little TikTok famous 🤷♀️) has been so incredibly healing.

If you suspect that your brain is wired differently, the best thing you can do is to learn more about how it works. Having ADHD isn’t laziness or a moral failure. You have a brilliant, resilient mind that may need guidance in assimilating into a neurotypical world. So, ask the questions, pursue that pathway bravely. The other side is a beautiful place.

You Might Also Like