This Year’s MacArthur Fellows Include a Hula Master. It’s Been a Long Time Coming.

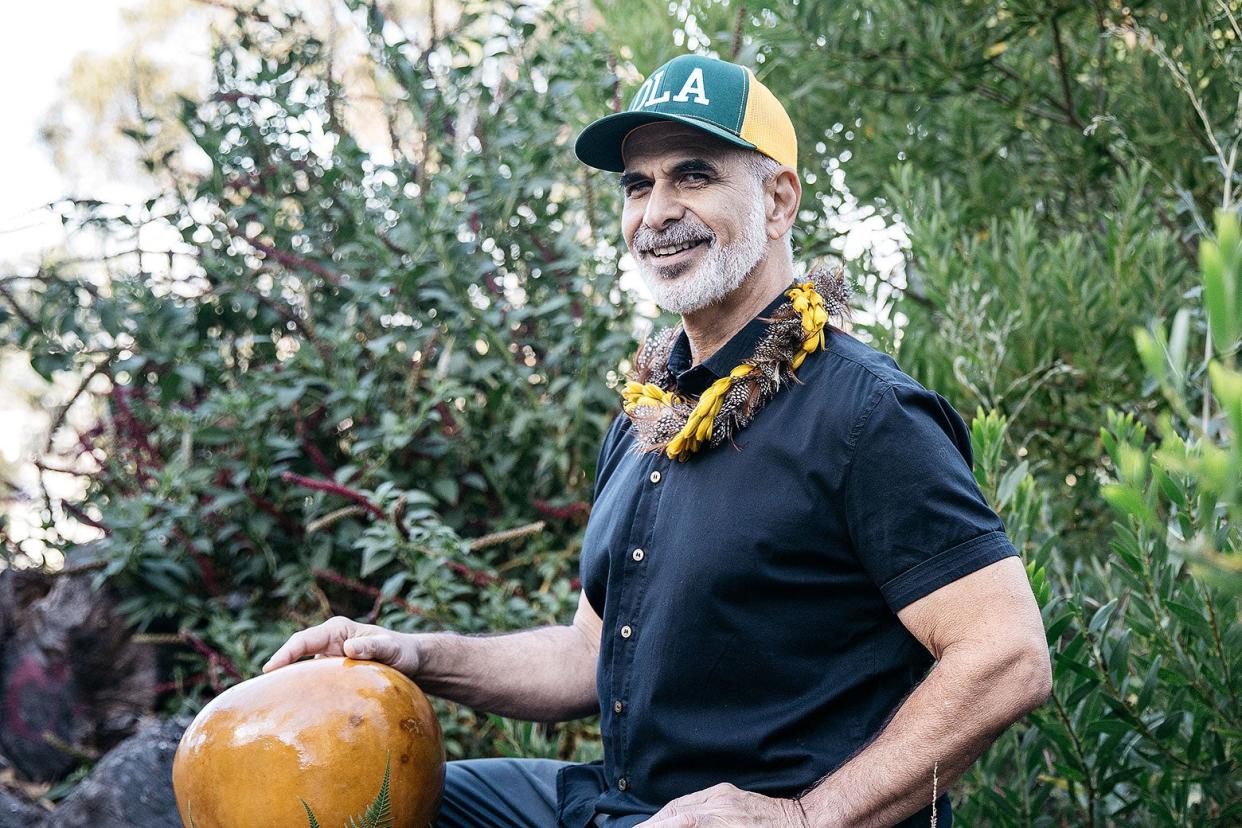

Among the 20 winners of the prestigious MacArthur Foundation fellowship announced Wednesday were scientists, engineers, composers, legal scholars—and one hula dancer. Patrick Makuakāne, a 62-year-old kumu hula, or master teacher, lives in San Francisco and runs the hula school and company Nā Lei Hulu I Ka Wēkiu, which blends classical hula dance with modern and contemporary music and theatrical flair. The citation on Makuakāne’s MacArthur—often referred to as a genius grant—calls him a “cultural preservationist,” but in a lively conversation just hours after the announcement, he revealed himself to be something different: an artist working not to preserve his culture in amber, but to innovate and transform it into something new. I spoke with him about how hula portrays masculinity, his MacArthur guilt, and what he’ll do with his $800,000 award. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Dan Kois: What a day it’s been for you. Have you heard from a million people asking if they have to call you a genius now?

Patrick Makuakāne: I’ve gotten a lot of calls. You know, I am living my little slice of the world in San Francisco doing hula—I get some attention, but it’s all local attention. To suddenly be on this national level is pretty crazy! And it comes with an immense amount of responsibility. I feel joy, and responsibility, and guilt.

Why guilt?

To be honest, I was speaking with a Native American and an African American who are in the class with me, and all of us expressed this intense amount of guilt. You know, we’re artists who are entrenched in our community. We recognize that it’s the community that supported us and led us to this award. And there are so many outstanding people who are doing fantastic work in the community, and you’re like, “Why do I get recognized?” But there you are, Blanche. Stop crying about it, and start making stuff.

For many mainlanders, hula is just something they encounter in tiki bars or on TV.

They have no idea what it truly represents! I’m an evangelist about hula. Hula is such an important, immersive, expansive part of our culture. It helped to bring the culture back from extinction in the ’70s, during the Hawaiian Renaissance. Everybody says it was music and wayfaring, and I say boldly that it was hula that did it. I’m biased, but you can be biased and right at the same time! Many people my age found a way to express their native identity through hula. That opens the door to so many aspects of our culture that was closed before. We can be proud to say we’re Hawaiian.

It gives you a language to speak about your origins.

Because hula is a language. King Kalākaua, who was king from 1874 to 1891, said, “Hula is the heartbeat of the Hawaiian people.” I roll my eyes at that sometimes—I’m not mocking the king, but people say it all the time, it’s like, “Find a new line.” But it’s true! It gives so many of us life.

I think people don’t understand what a difference there is between watching it and doing it.

Yes! Take a hula class, and it’s really a class of culture. Dance is like 40 percent of it. Whenever I teach a new class, the very first day, we just sit in an ’ai ha’a—that’s basically like a plié stance in ballet—and we just go through language, teaching the new words and the new calls in Hawaiian. And I know they’re thinking, What the fuck is this? I came to do a dance class!

You’ve developed what you call a unique form of hula, “hula mua.” How does this differ from traditional hula?

A lot of people think that hula tells a story. But really, the poetry, the song, the chant, those are the main vehicle of expression. It’s the song that tells the story. Here in San Francisco, Hawaiian-language songs and chants are the major part of the repertory. But when I do it in English, people get it! “Oh—the words match the motion!” And so people are understanding it, rather than: You sit your ass out in the audience, and we’ll be on stage, and the dance may seem pretty to you, but it has no meaning.

One of our signature pieces is “I Left My Heart in San Francisco.” That song is a perfect example of how Hawaiian songs are written. It tells you about a special location you live in. It gives you the environmental characteristics of that place, that explain why it’s unique. And then you add a love interest who’s specific to that location. Whenever we dance that, people just get it, the connection between place, environment, movement, love.

There’s this guy who comes up to me, he moved here from Hawai’i, he’s gay, and when we do that song, he says, “Coming to San Francisco as a gay man, that song says everything!” I’m like, “I get you, bro.” Dancing hula is the best way to demonstrate your aloha for the place you love.

You recently created a show called Māhū, about gender fluidity in Hawaiian culture. What was your inspiration for that?

I have all these incredibly talented friends who are māhū! It was 2020, and transgender people were in the news, with Trump and the military and, you know—it was the conversation that was happening. I wanted to do a show with my transgender friends who are artists—not to have them onstage rallying their flag, but to have them share their talent, their singing, their dancing. How can you deny these amazing people a seat at the table when you’ve seen their artistry?

At first I was going to call the show Trans Pacific. You know, because we brought them across the Pacific Ocean. So clever. But then I realized, this word, māhū, something that when you were called this as a child, on the playground, you couldn’t imagine … so let’s take it back. Here in San Francisco a lot of people don’t get it, but when I took that show back to Hawai’i, people totally knew what I was talking about. And to work with these incredible artists really made me better. You’re doing a show called Māhū, you better make sure that every damn dancer out there is showcased, has the best costumes, the best lighting—you gotta step it up.

Hula is very focused on tradition, this long lineage of chants and dances. But you’re pushing against that in some ways. Do you see conflict between your style and traditional hula? Do you see traditionalists getting angry at you?

I used to. I don’t anymore. There used to be more controversy, but now people are more accustomed to my work. And living in San Francisco for almost 40 years, I’ve unshackled myself from that fear. I do have training in that long tradition. I graduated as a kumu hula in a traditional ceremony. I have that foundation, that anchor, and that allows me to go close to the edge. I don’t take traditional dance elements and turn them on their head. But there’s no law against creating a hula to Roberta Flack’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face.”

So the idea is your dancers are doing traditional moves, but to nontraditional songs.

It’s more stylized, but you can see the fundamentals of it. My dancers are trained hula dancers! They don’t have ballet or hip-hop experience. It’s all hula. We’re not gonna jump, we’re not gonna spin, we’re not gonna do the things that take us out of that hula space. I mean, here and there I get a little bit wacky, but mostly not.

And, of course, I’m living in San Francisco—my god. You could walk around with a sock on your ding-dong and nobody would bat an eye.

So living in San Francisco has affected your work?

It’s really given me an appreciation for subversion in art. When I first moved here in 1985, we ended up going to this huge department store. Gays were demonstrating against Nordstrom, against their hiring policies, I think. And we were in this huge elevator just packed with men, and at the sound of a whistle, they all yelled, “We’re here! We’re queer! And we’re not going shopping!” Well, I’ve never seen anything like this in Hawai’i. This idea of protest, plus theater, plus wit—how that can make you remember something—it really spoke to me. I just liberated myself and went for it. I decided to create whatever felt right for me.

Do you still have people in Hawai’i? How does your work play there?

Oh yeah, family, friends, artists. I always take it back. I always say, “Here, guys, what do you think, you still like me?” And the shows get a great response. Of course there are people who don’t like it and think hula should just be in a box, with only certain kinds of movement. I totally understand that. But I think we need to reframe the conversation about tradition. It shouldn’t be a static representation of heritage. We look back and we can see so clearly: Our ancestors were innovative! We can be innovative, too.

You studied with Robert Cazimero. I only know him as a musician, with the Brothers Cazimero. I didn’t know he was a kumu hula.

Oh, man! He was hugely influential in my work. He was considered a rebel, a renegade, in hula. In my mind, he should be receiving this award before me. He was an innovator living in a place where people didn’t think you could do that. I’m in San Francisco, but he was in Hawai’i, in the 1970s, with people saying, “What you doing! That’s not right!” For men, dancing hula, that was like, ooooh. In the ’70s, a man dancing hula was a political statement already.

And the way he approached masculinity. It was totally different. Look, audiences want that warrior, tough-guy expression in hula. I get it. It’s invigorating! It’s very masculine. But he cultivated a style which was masculine yet graceful, with a more artistic vibe. We weren’t just doing dynamic, grrrrrr, warrior moves. It was hard!

You said you feel a little guilty, that this creates a responsibility. So what does that mean for your work going forward?

I’ve thought about it a lot. I don’t know exactly what I’m going to do with all this money yet. But I know one of my major plans is to collaborate and work with other Native Hawaiian artists whose work has influenced mine, and give them a bigger place in the national conversation around art and dance. That feels like the right thing to do.